This website uses different cookies. We use cookies to personalize content, provide social media features, and analyze traffic to our website. Some cookies are placed by third parties that appear on our pages. You can find more information and options to choose from in our Privacy Policy and Configurations for usage.

- Learning activity

- Learning outcomes

- Pedagogical Recommendations

- Activities

- Glossary

- Appendices

- Appendix I – Preparatory work handout for students

- Appendix II – Photo analysis task

- Appendix III – Stereotypes about Jews in Moldova (2018)

- Appendix IV – Monument to the Victims of the Jewish Ghetto

- Download guide

A forgotten page of history: the Chișinău ghetto

Вікторыя Піла ліцэй Праметэй-Прим, Кішынёў, Малдова / Александру Сеу Тэарэтычны ліцэй ім. Міхая Эмінеску, Единец, Рэспубліка Малдова

16-19 гадоў

45 min (+ 45 min prepratory work)

Key question: How does the Chișinău ghetto illustrate the tragedy of the Jews during World War II?

Learning outcomes

Students will:- Reconstruct the history of a place to understand how the way people lived in the past forms a link with a community’s present and future.

- Combat prejudices concerning, and stereotypes of, religious and ethnic minorities.

- Learn tolerance, cultural diversity and empathy for the victims of the Holocaust during World War II.

- Understand historical concepts such as continuity and change, cause, and consequence.

Pedagogical Recommendations

This lesson is part of a series of topics taught in class on World War II. It should be carried out after students have already learned about the most important aspects of the war and the specifics of the Holocaust. The lesson is about local history, but it is directly related to the events of 1941-1942 and the tragedy of the Jews in the 20th century.Students will analyse historical texts, memoirs of survivors, period photographs, and take a virtual tour through the Chișinău ghetto.

Activities

In preparation for the learning activity, students receive an exercise (see Appendix I). They should read the texts about the Chișinău ghetto and the history of Moldova’s Jewish population before World War II.Stage 1: Preparatory work consolidation. 10 minutes

Students should work in small groups of 3-4 and answer the following questions based on the texts they read in preparation.

Questions for Text A:

- What were the professions of the Bessarabian Jews?

- Why did Jews predominantly live in cities?

- Why did the Russian and Romanian authorities persecute the Jews?

- Why were Jews considered suspicious in Romania between World War I and World War II?

- For what purpose was the Chișinău ghetto designed?

- How do you think the local population reacted to the construction of the ghetto?

- Why did the Romanian authorities decide to deport the Jews to Transnistria?

- Were the Romanian authorities carrying out German orders or promoting their own anti-Jewish policy?

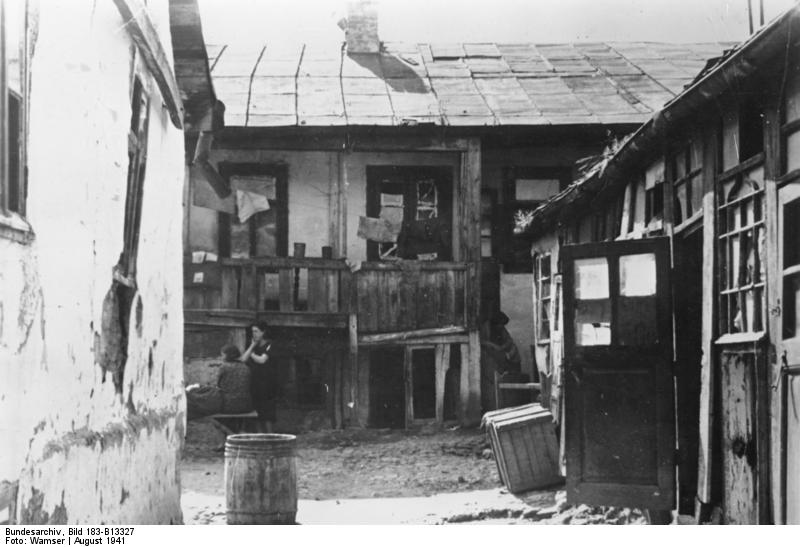

Stage 2: Analysis of photos. 10 minutes

In the same groups, students should look at the photos and answer the questions (see Appendix II).

Stage 3: Stereotypes. 10 minutes

According to a study conducted by the Council for the Prevention and Elimination of Discrimination and for Ensuring Equality (2018), Jews are not among the most rejected social groups in Moldova (see Appendix III). However, there are a number of stereotypes about them. Students should look at the table and, in small groups, discuss whether a similar study conducted in the late 1920s or early 1930s would have shown the same results.

Stage 4: Analysis of a monument. 15 minutes

Students are given the photo and text about the Monument to the Victims of the Jewish Ghetto to study (see Appendix IV). They should answer the questions below, which the teacher should project onto the board:

- How does the history of the Chișinău ghetto illustrate the tragedy of the Jews in World War II?

- In 2018, Victor Popovici, project manager at the Agency for Inspection and Restoration of Monuments, brought two international commemorative projects to Moldova. The first, initiated in Germany, involves the installation of ‘Stumbling Stones’ in front of houses where victims of Nazism lived. And the second, suggestively named ‘Last Address’ in Russian, involves the installation of plaques on the facades of houses where victims of Stalinist repression lived. Do you think they are necessary in our country? Why/why not?

- Is it good to have a memorial like this?

- Has this lesson made you think of how you, as a young citizen, but also a future adult, should think about minorities and how to treat them?

Glossary

Here you can find definitions for the words in bold below.- Bessarabia – a region in eastern Europe that was ruled successively (from the 15th to 20th century) by the Principality of Moldavia, the Ottoman Empire, Russia, Romania, the Soviet Union, Ukraine, and the independent Republic of Moldova. It is bounded by the Prut River on the west, the Dniester River on the north and east, the Black Sea on the southeast, and the Chilia arm of the Danube River delta on the south.

- Ion Antonescu – a Romanian marshal and statesman who became dictator of the pro-German government during World War II.

- The Iron Guard (also known as the Legionary Movement) – an anti-democratic, anti-communist and anti-Semitic political party in Romania between 1927-1940.

- Pogrom – an organised massacre of a particular ethnic group, in particular that of Jewish people in Russia or eastern Europe.

- Transnistria – a region now lying between Moldova and Ukraine. Its name means beyond the Dniester River, and it was part of Romania from 1941-1944.

- Wehrmacht – the armed forces of Nazi Germany between 1935-1945.

Appendix I – Preparatory work handout for students

Read the information about the Jewish community in Moldova before World War II (Text A) and a short description of the Chișinău ghetto (Text B).Text A

The first Jews appeared on the territory between the Prut and Dniester rivers in the 1st century CE with the Roman legions who had conquered the ancient territory of Dacia. From the 15th century, Moldova was an important transit stop for Jewish merchants travelling between Constantinople and Poland. By the 18th century, several permanent Jewish communities had been established in urban settlements like Orhei, Soroca, Beltsi, and Ismail. Most of the Jews were engaged in trade. The 1803 census indicates that there were Jews living in all 24 Moldovan cities, as well as in many villages and towns. In 1836, the Jewish population of Bessarabia had grown to 94,045, and by 1897 already numbered 228,620, representing 11.8% of the province's population. In 1897 the Jewish population of Chișinău constituted almost half of the entire population (50,237, or 46% of the population). Pogroms were not uncommon: one in 1903 was particularly notable and caused international outrage. Thousands of Moldovan Jews emigrated, and the United States publicly condemned the massacre and imposed trade restrictions against the Russian Empire, of which Moldova was a part.

In 1918, Bessarabia (the eastern part of Moldova) became part of Romania. The Jewish community in the area was given Romanian citizenship and was able to open Jewish day schools, though they were generally considered suspicious in the eyes of the Bucharest authorities, who saw them just as the other minorities of Bessarabia: potential agents of Moscow. In the 1930s in Romania, an anti-Semitic movement developed, which was visible in education, politics and social relationships. During the worldwide economic crisis at the beginning of the decade, the Iron Guard, a revolutionary fascist movement, and other anti-Semitic organisations witnessed a steady growth in popularity. In 1934, a law was passed that forced businesses to employ at least 80% Romanian workers. This law represented the first step towards harsher legislation to come: the suspension of newspapers owned by Jews; the annulment of railway passes of Jewish journalists; the annulment of all licences granted to Jews to sell alcohol in rural areas; and a law for the revision of their citizenship status. The already existing anti-Semitic legislation was extended by the Marshal Ion Antonescu dictatorship, including expropriation of Jewish property. After Operation Barbarossa on 22 June 1941, the commercial and industrial property of the Jews of Bessarabia was confiscated; they were forced to wear the Star of David, and ghettos were established for “eastern Jews”.

Sources: ‘Moldova’, JGuideEurope, accessed 12 June 2022.

Scheib, A., ‘Moldova Virtual Jewish History Tour’, Jewish Virtual Library, accessed 12 June 2022.

Text B

On 16 July 1941, Romanian troops entered Chișinău together with units of the 9th Army of the Wehrmacht. The exact number of Jews remaining in the city at the time is not known. Some had been deported by the Soviet government before the war; some were evacuated or drafted into the Red Army. The rest could not imagine what awaited them. On 24 July 1941, the governor of Bessarabia, General Voiculescu, issued an order to create camps for Jews from the countryside and to establish the Chișinău ghetto. The ghetto was established in the lower part of the city; there were only two entrances. The population was doomed to starvation. The commandant of the ghetto prohibited selling products to the Jews until 11am, and after this hour they could no longer be obtained anyway. The number of deaths caused by malnutrition and illnesses reached 10-15 per day and were included in reports as “death by natural causes”. Some peasants, disregarding the risks, brought food. The Jews were left to their fate and sold their things on the market, as it was practically the only way of survival. In the mornings, Romanians and Germans came to the ghetto and took men, women, and children for domestic work. Employers not only did not pay them, but did not feed them either. The commandant noted down the disobedient ones, and at the first opportunity the “guilty” disappeared forever.

According to data from 19 August 1941, there were 9,984 Jews in the ghetto (2,523 men, 5,261 women, 1,160 girls and 1,040 boys). In the middle of September, there were almost a thousand more people in the ghetto. Of the 11,525 prisoners, there were 4,168 men, 4,476 women and 2,901 children. This increase in population was due to the fact that Jews from the surrounding settlements were gathered into the Chișinău ghetto.

The Chișinău ghetto was one of several ghettos set up in this period. The establishment of the ghettos and the camps was the precursor to an attempt by the Romanians to “cleanse” Bessarabia and Bukovina (a region north-west of modern-day Moldova) of “the Jewish elements” via mass deportations from the camps and ghettos across the country to the other side of the Dniester.

From 5 August 1941, Jews of the city were required to wear the Star of David. The deportation of Jews to Transnistria, an area between the Dniester and Bug rivers, began on 8 October, and during the deportations from Bessarabia, the sheer criminal incompetence, lack of preparation, and extreme callousness of the Romanian military resulted in a staggering death rate among the Jews. The Jews were deported on foot, and those who could not keep up with the forced marches (mostly the sick, the elderly and children) were shot on the spot by Romanian and Ukrainian guards. The most sinister camps were Bogdanovka and Ahmetchetka where Jews died of starvation or were executed. As records were destroyed by Romanian and Nazi authorities before the arrival of the Soviet Red Army in 1944, there are little or no data about the inmates of these camps.

Source: ‘Life in Chișinău ghetto’, JewishMemory, accessed 12 June 2022.

Appendix II – Photo analysis task

Look at the photos and answer the questions beneath.Photo 1:

File:Bundesarchiv_Bild_183-B12267,_Kischinjow,_festgenommene_Juden.jpg

- How many people were there in the ghetto?

- Which nationality were they, as far as you can see?

- How old are they?

- How are they dressed?

- What are they waiting for?

- What might they be thinking about?

- What was their ultimate fate?

- In pairs, describe the living conditions in Chișinău ghetto.

Appendix III – Stereotypes about Jews in Moldova (2018)

| Positive | Neutral | Negative |

| Intelligent - 49.4% | Calm - 12.9% | Sly - 33.8% |

| Cooperative - 26.4% | Enjoy resting - 0.6% | Stingy - 24.3% |

| Daring - 20.6% | Rich - 0.4% | Have a certain smell - 10% |

| Hard-working - 14.6% | Are secretly ruling the world - 8.8% | |

| Caring - 12.5% | Lazy / don't work - 8.5% | |

| Loyal - 10.5% | Are getting rich illegally - 8.4% | |

| Helpful - 8% | ||

| Respectful - 7.9% | ||

| Kind - 1.3% | ||

| Resourceful - 0.7% |

Appendix IV – Monument to the Victims of the Jewish Ghetto

The monument to the victims of the Jewish ghetto on Jerusalem Street marks the spot of the main entrance to the former ghetto established in the lower part of Chișinău in July 1941, shortly after German and Romanian troops entered the city. Over 11,000 people – men, women and children – were brought there. The monument pays tribute to the Jews imprisoned and murdered in the ghetto during World War II. It was erected on 22 April 1993 and designed by sculptor Naum Epelbaum and architect Simeon Shoihet. The monument was built with funds from I. Simirean, a private businessman, and the Jewish Agency ‘Sohnut’. The memorial’s centrepiece is a large bronze figure of the prophet Moses, with his left hand on his heart and his right hand holding the Scripture. The statue stands on a pink granite pedestal and is set against a broken red granite wall, at the centre of which is a void in the shape of a shattered Magen David (Star of David). The inscription – in three languages: Hebrew, Romanian, and Russian – on the back of the monument, reads: “Martyrs and victims of the Chișinău ghetto! We, the living, remember you!”

In 2013 the monument was vandalised – a fascist swastika was drawn on the memorial stone. In 2016, at the initiative of the President of the Jewish Community of the Republic of Moldova Alexandr Bilinkis, the monument was renovated and refurbished.

Every year on 27 January there is an official memorial rally to commemorate the victims of the Holocaust.

Download guide

Дадатковыя

матэрыялы

ўрока

Пачатак і заканчэнне Другой сусветнай вайны

Дзеці ў гады Другой сусветнай вайны

Памяць і мемарыялізацыя Другой сусветнай вайны ў розных краінах

Гвалтоўны ўгон моладзі на працу ў Германію падчас Другой сусветнай вайны

Змена дзяржаўных межаў у выніку Другой Сусветнай вайны

Наступствы Другой сусветнай вайны