This website uses different cookies. We use cookies to personalize content, provide social media features, and analyze traffic to our website. Some cookies are placed by third parties that appear on our pages. You can find more information and options to choose from in our Privacy Policy and Configurations for usage.

The Stumbling Stones project as an example of victim commemoration

Крыстаф Майснер Heinrich-Heine-Universität, Дзюсельдорф, Германія

15+ гадоў

45 min

3082 слоў

Key question: What can the Stumbling Stones teach us about the remembrance of repressions and their victims in the past, present, and future?

Learning outcomes

Students will:- Learn tolerance, cultural diversity, and empathy for the victims of the Holocaust during World War II.

- Think critically about the presentation of the past in memorials coming from citizen-led or grassroots initiatives.

- Train their analytical and critical thinking skills.

- Use empathy to understand the past and the way it is viewed in the present.

- Use the past and the present to form opinions on the future.

Pedagogical recommendations

The Stumbling Stones is a civil society project that aims to commemorate victims of the mass murder committed by the National Socialist regime. It is a memorial integrated into the urban landscape in the form of small stones set into the pavement. This memorial and its complex history form the basis of this learning activity.

In order to carry out this learning activity, it is important that the students have a basic knowledge of National Socialism, its ideology and crimes; above all, knowledge of the Holocaust is a fundamental prerequisite. It is only on the basis of this knowledge that students can reflect on the questions of which groups of victims should be remembered. Carrying out such a learning activity without this prior knowledge should be avoided, as this can lead to an overwhelming demand on the students and a failure to achieve the outcomes of the learning activity.

Activities

To prepare for the lesson, the teacher selects 5-6 Stumbling Stones using the Stumbling Stones website or their own knowledge. The selected examples of Stumbling Stones should cover the diversity of the various victim groups. An excursion to see nearby Stumbling Stones is also an option.As preparation for the learning activity, students are given: 1) a text with background information about the Stumbling Stones (see Appendix I); and 2) an interview with Gunter Demnig, who initiated the project, in which he outlines his motivations (see Appendix II). Using the materials, students will learn about the initial ideas of Demnig, and they should think about whether the stones are still relevant for contemporary Holocaust remembrance. The preparation should be carried out individually before the lesson.

Stage 1: Discussion of the preparation. 5 minutes

In groups of 3, students discuss the preparatory exercise and what motivated Demnig to expand the Stumbling Stones project from the first stone (which was a memorial to one specific date) to victims of the Holocaust and later to a range of victims of National Socialist tyranny.

Stage 2: Discussion and comparison of Stumbling Stones. 20 minutes

In groups of 3, students compare and discuss two Stumbling Stones handed out to them in terms of design and the information provided on the blocks (see Appendix III for some examples). Here the students also discuss whether the Stumbling Stones are an adequate form of memory. The basis for this is the knowledge acquired in the preparatory work and subsequent discussion.

The aim is to get students thinking about whether this form of remembrance is relevant today.

Stage 3: Discussion of the future. 10 minutes

Based on their reflections in Stage 2, students next look to the future and discuss their thoughts about which categories of victims should be remembered in the future and which ones have already been forgotten today. This is a plenary session.

Stage 4: Final reflection. 10 minutes

Finally, guided by the teacher, the class discusses to what degree the learning objectives were met during the lesson, and what the students personally have learned. A starting point for the discussion could be the core question: What can the Stumbling Stones teach us about the remembrance of repressions and their victims in the past, present, and future?

Assessment

Below are several points that can be used as a suggestion of how the teacher may assess the learning activity during the lesson:- At what level does the student use observation and analytical skills? How well do they distinguish between important and unimportant information?

- How well thought through is the student’s contribution to the homework discussion? Is it clear that they have thought about the subject at home?

- How much does the student contribute?

- How skilled are the students in cooperating and working together as a group?

- How do the students handle the quotes and reflect on them critically?

- Was the student willing to take part in the discussion and able to use the acquired knowledge to consider a possible future?

Glossary

Here you can find definitions for the words in bold below.- Auschwitz Decree – a decree signed by Heinrich Himmler on 16 December 1942 ordering the deportation of all Sinti and Roma living in the German Reich with a view to completely destroying them.

- Plaque – an ornamental tablet, typically of metal or wood, that is fixed to a wall or other surface in commemoration of a person or event.

- Reichspogromnacht – a pogrom against Jews, carried out by the SA (Nazi paramilitary troops) as well as civilians on 9/10 November 1938. The windows of Jewish-owned shops, buildings and synagogues were smashed, giving the violence its other name of Kristallnacht, or the Night of Broken Glass.

- Yad Vashem – the official memorial site to the victims of the Holocaust in Israel.

Appendix I – Student handout: Background information on the Stumbling Stones project

The Stumbling Stones project was initiated in 1992 by artist Gunter Demnig. It consists of small memorial plaques laid in the ground intended to commemorate the fate of people who were persecuted, murdered, deported, expelled, or driven to suicide during the National Socialist era in Germany. On 16 December 1992, the 50th anniversary of Heinrich Himmler's order to deport “gypsies” (the so-called Auschwitz Decree), Demnig set the first stone in the pavement in front of Cologne’s historic town hall. In the following years, Demnig developed the project to include and represent all persecuted groups. On 4 January 1995, more stones were laid in Cologne on a trial basis without permission from the authorities. Later, the laying of the stones was officially approved and thus acquired an official character. This subsequently developed into the world's largest ‘decentralised memorial’.As a rule, the inscriptions on the golden stones begin with the phrase “Here lived”, followed by the name of the victim and the year of their birth; the year of deportation and place of death are also usually noted. The Stumbling Stones are set into the pavement directly in front of the last known place of residence of the victim. In April 2022, Demnig laid the 90,000th stone. Apart from Germany, Stumbling Stones have been laid in 29 other countries so far, including the Netherlands, Austria, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Hungary. There are also isolated Stumbling Stones in Russia, Ukraine, France, and Romania. They do not, however, do justice to the scale of persecution in these countries. The Stumbling Stones are usually maintained and cleaned by local residents, who also lay flowers and light candles on commemorative days such as 9 November.

Source: Adapted from ‘Stolpersteine’, Wikipedia, and the official Stumbling Stones website, accessed 17 February 2023.

Appendix II – Interview with Gunter Demnig

Mr Demnig, how did you come up with the idea of laying Stumbling Stones for victims from the Nazi era?There was preliminary work in Cologne in May 1990, namely a written mark on the street: May 1940, 1,000 Roma and Sinti. In May 1940, 1,000 Roma and Sinti were deported from several large West German cities. You could say that these deportations were like a dress rehearsal for the later deportation of the Jews. That was the trigger to bring the names back to where the horror began, where the people had their homes and were taken away.

This then gave rise to the idea of laying Stumbling Stones?

The basic idea was to bring back the names. The first idea was to screw a classic plaque on the wall. For the project in Cologne, I had the great fortune to meet a Jew from Leipzig who worked at WDR [West German Broadcasting]. He said to me, “Gunter, you want to screw memorial plaques for Jewish victims on the walls of houses? Forget it. 80 percent, if not 90 percent of the house owners would never agree to that.”

What conclusion did you draw from that?

I remembered Rome and St. Peter's Basilica. There you walk thoughtlessly over the tomb slabs where there really are bones underneath. So, I went to the Museum of Sepulchral Culture to find out more. There I was told that when people walk over gravestones, it increases the honour of the person who is buried there. I must admit, at first, I had some reservations. I wrote to the Jewish community in Cologne and asked for advice. Nine months later, the rabbi invited me and said something similar could be done. These are not gravestones, but merely memorial stones. He also told me, “A person is only forgotten when his name is forgotten.”

Do Stumbling Stones have another advantage over memorial plaques?

After the first stones were laid in Cologne, I went to my car. When I turned around again, I saw the first passers-by stop. Anyone who sees the stone and wants to read the text on it has to bow towards the victim. This is another aspect that I had not thought about at the beginning.

Why is it important to you to remember the victims of the Nazi era?

I think it’s especially important for the younger generation. We work a lot with school pupils, and I notice that they experience a different history lesson through the Stumbling Stones. For example, they might open a book and read: “Six million Jews were murdered in Europe alone.” If they investigate further, they find out that there were another six million, maybe even eight, who were murdered by the Nazis for other reasons. That is an abstract figure. It remains unimaginable. But when the pupils then come to grips with the fate of a family in their own environment, they really get to know what happened there. It's a completely different kind of history lesson. And I have noticed that young people are interested in the subject. They want to know how something like this could happen in the land of poets and thinkers. But we also do it for people who ask themselves today, why don't I have a grandmother or great-grandmother?

When did you lay the first Stumbling Stone?

The first stone was laid in 1992, but the project really got going for me in 1996 in Berlin, during a time when I was going through a lot of difficulties. We did it illegally at first. We wouldn't have got permission because stumbling or falling is taken seriously. A secondary school pupil, interviewed by a reporter after the stones had been laid, found a very good way of expressing their experience of the stones. The reporter asked, “But Stumbling Stones are dangerous, don't you fall on them?” And the pupil replied, “No, you don't fall, you trip with your head and your heart.”

What happened after you really started with the Stumbling Stones in Berlin in 1996?

In 1997 there was an artists' meeting near Salzburg. There I laid the first two stones for murdered Jehovah's Witnesses. Then there was a break, and from 2000 onwards things really took off with the permits, almost simultaneously in Berlin and Cologne. There are now almost 1,300 places in Germany and 1,500 all over Europe where we have laid Stumbling Stones.

How many Stumbling Stones have you laid so far?

So far, we have laid more than 80,000 stones all over Europe, in a total of 26 countries. The basic idea behind it was that wherever the Wehrmacht, the SS, or the Gestapo did their evil deeds, Stumbling Stones should also appear there symbolically. Visitors recognise the stones, and that too is interesting. Then they go to Rome and realise that it happened there too. It works the other way round as well: a class trip to Berlin, the pupils see the stones in Hamburger Straße, come home and ask what happened here in our town. These are the effects that I find important and where I have to say that it must therefore continue. Just in case, I have also set up a foundation so that it will continue in any case.

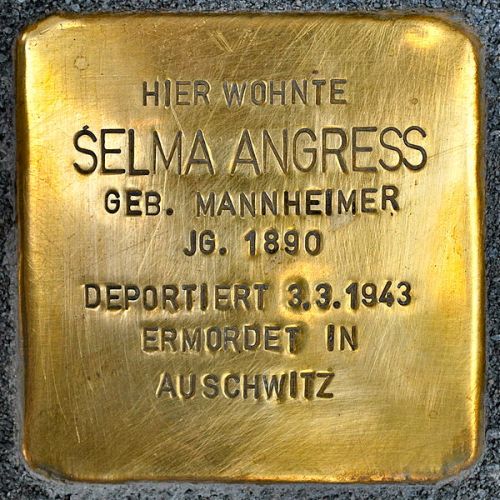

Appendix III – Examples of Stumbling Stones

1. [Text: By order of the Reichsführer SS of 16.12.42 - Tgb. No. I 2652/42 Ad./RF/V. - Gypsy mongrels, Roma Gypsies and non-German-blooded members of Gypsy clans of Balkan origin are to be selected according to certain guidelines and sent to a concentration camp in an action lasting a few weeks. This group of persons is referred to in the following as 'Gypsy persons'. They were sent to the Auschwitz concentration camp (Gypsy camp) family by family, irrespective of the degree of mongrelisation.]

Schönhauser Allee 187, Berlin, laid 20 August 2010

[Text: Here lived Selma Angress, born 1890, deported 3.3.1943, murdered in Auschwiz]

Bötzowstraße 20, Berlin, laid 7 August 2014

It is known from the information in the central database of Yad Vashem that their son Shimon (formerly Robert) Angress survived the Holocaust. The laying of the Stumbling Stone took place in the presence of the Angress’s descendants who had since moved to Israel.

Selma Mannheimer, born 10 October 1890 in Frankfurt am Main, daughter of Jeanette Blumenthal and Abraham Mannheimer; married Paul Ludwig Angress on 3 May 1921 in Frankfurt am Main; forced labour at Osram in Berlin from 25 October 1940 to 27 February 1943; deported on 3 March 1943 with the 33rd Osttransport from Berlin to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Mendelssohnstraße 3, Berlin, laid 24 June 2015

Heinz Behrendt, later Chaim Baram, born on 5 August 1919 in Berlin, died in 1975 in Kibbutz Naan in Israel. Married first to Charlotte Behrendt, née Rotholz, and later to Sara Baram, née Holländer. Deported on 14 November 1941 with the 5th transport to Minsk. From there to Maly Trostenez concentration camp, Majdanek extermination camp, Budzyn labour camp near Krasnik, Mielec labour camp, Wieliczka, Auschwitz-Birkenau, and Flossenbürg concentration camp. From there he was forced on the death march to Dachau. Liberated by American troops on 25 April 1945, Heinz Behrendt gave himself the name Chaim Baram. He went to Israel, married again and had four children with his second wife. In 1961, he testified in the trial against SS-Obersturmbannführer Adolf Eichmann. He never set foot on German soil again. Heinz Behrendt is one of the few survivors of the Minsk Ghetto.

A total of eight other family members lived in the basement flat, and additional Stumbling Stones were laid for them in 2017. The apartment building was demolished at the end of the 1960s and replaced by new flats in the 1970s.

The person who laid the Stumbling Stone for Behrend has laid three more Stumbling Stones in Berlin-Prenzlauer Berg (Rosa Schlagk, Herta Henschke, Hedwig Peters) and five Stumbling Stones in Berlin-Friedrichshain (Jenni Bukofzer, Samuel Bukofzer, Luise Bendit, Leo Bendit, Aron Bendit).

Straßburger Straße 19, Berlin, laid 27 November 2018

Quotes

Download guide

Дадатковыя

матэрыялы

ўрока

Пачатак і заканчэнне Другой сусветнай вайны

Дзеці ў гады Другой сусветнай вайны

Памяць і мемарыялізацыя Другой сусветнай вайны ў розных краінах

Гвалтоўны ўгон моладзі на працу ў Германію падчас Другой сусветнай вайны

Змена дзяржаўных межаў у выніку Другой Сусветнай вайны

Наступствы Другой сусветнай вайны