This website uses different cookies. We use cookies to personalise content, provide social media features, and analyse traffic to our website. Some cookies are placed by third parties that appear on our pages. You can find more information and options to choose from in our Privacy Policy and Configurations for usage.

- Lesson plan

- Abstract

- Notes for the teacher

- Core Question

- Objectives

- Tasks

- Methods

- Equipment

- Preliminary preparation

- Agenda and timing of stages

- Detailed lesson plan

- Part 1: Introduction / Brainstorming

- Part 2: Group work / Metaplan / Analysis of sources

- Parts 3: Discussion / Conclusions

- Appendix I: Introductory Images

- Appendix II: Maps

- Appendix III: Group 1 Materials – Brześć nad Bugiem → Brest

- Appendix IV: Group 2 Materials - Danzig → Gdańsk

- Appendix V: Group 3 Materials - Königsberg → Kaliningrad

- Appendix VI: Group 4 Materials - Lwów → Lviv

Lesson Plan

Anna Cherepova European Gymnasium, Moscow, Russia / Liudmila Gurinovich Belovezhskii Middle School, Belovezha, Belarus / Taras Oleksyn Children’s Centre of Tourism, Sport and Excursions, Lviv, Ukraine / Anna Skiendziel Complex of Technical and Secondary Schools No. 2, Katowice, Poland

16-19 years

90 minutes

Abstract

After the end of WWII, borders in Eastern Europe changed dramatically. Some cities that had been in one country found themselves on the other side of the border; their names were changed, and the effects on their populations were varied and wide-reaching. Students will work with maps and primary sources that show the effects of border changes resulting from WWII in four different areas of Central/Eastern Europe. They will work in groups, learning the history of these places, and investigating how WWII led to border changes and consequential changes to place names, and the effects on local populations. (Changes to borders and place names are a good way of easily visualising change.)

Notes for the teacher

-> The chosen examples are just a selection; looking through the lens of these examples, the students can come to understand the situation in other, similar towns and cities.

-> The Metaplan method (explained below) relies on vague, open questions; there are no wrong answers, and the students are free to say and investigate whatever they want.

-> Feel free to adapt the sources based on the needs of your class.

Core Question

How did border changes resulting from WWII affect the lives and fates of the people living in four cities?

Objectives

To create a picture of the changes in the political maps of Central/Eastern Europe as a result of WWII (by investigating four case studies), and to demonstrate the effects these changes had on people.

Tasks

- Students are shown pictures from each of the four examples. They will brainstorm based on a few questions given by the teacher.

- Students are divided into four groups. Each group will analyse some primary sources based on the four case studies, and create a short presentation based on a few questions.

- Students will present their findings to the class.

- There will be a final discussion which returns to some of the questions asked at the start of the lesson.

Methods

The purpose of the Metaplan method is to break down the structure of a traditional brainstorming/analysis exercise, by guiding students with questions that help them reach conclusions in a logical manner. In this way, the students add structure to their thought process and become aware of how they come to reach their conclusions - hence ‘Metaplan’. The questions in the Metaplan are kept deliberately broad, so that students have free reign to voice their thoughts. The role of the teacher is to provide a space for students to reach conclusions on their own, which may include asking more specific questions where necessary, or providing direct feedback during the exercise. The method is particularly popular in Poland.

Equipment

Group materials, a board, a projector (desirable)

Preliminary preparation

Knowledge of relevant aspects of WWII, including of deportations, to be refreshed. The teacher can choose how best to do this based on the class, e.g. a homework exercise or some short guiding questions at the beginning of the lesson.

Agenda and timing of stages

| Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Introduction / Brainstorming | Group Work / Metaplan / Analysis of sources | Answers / Presentations | Discussion / Conclusions |

| 10-15 minutes | 30 minutes | 20 minutes | 20-25 minutes |

Note: If more time is needed for Part 2, Part 3 can be shortened accordingly.

Part 1: Introduction / Brainstorming

10-15 minutes

Introduction

The lesson begins with the teacher showing photographs, preferably using a projector, though the photos can be printed if necessary. The pictures are from Gdańsk, Kaliningrad, Lviv, and Brest:

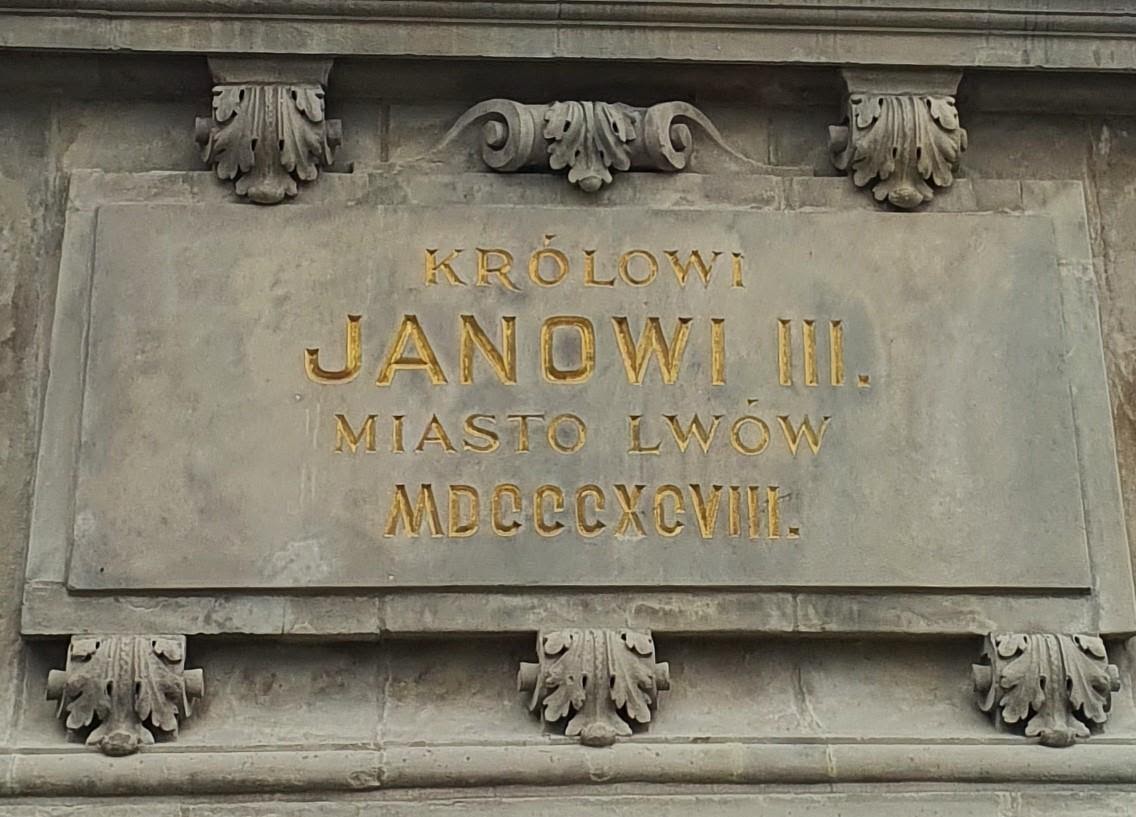

- Gdańsk (Poland) - monument to the Polish king Jan III Sobieski, with the inscription “to King Jan III, the city of Lviv, 1898”.

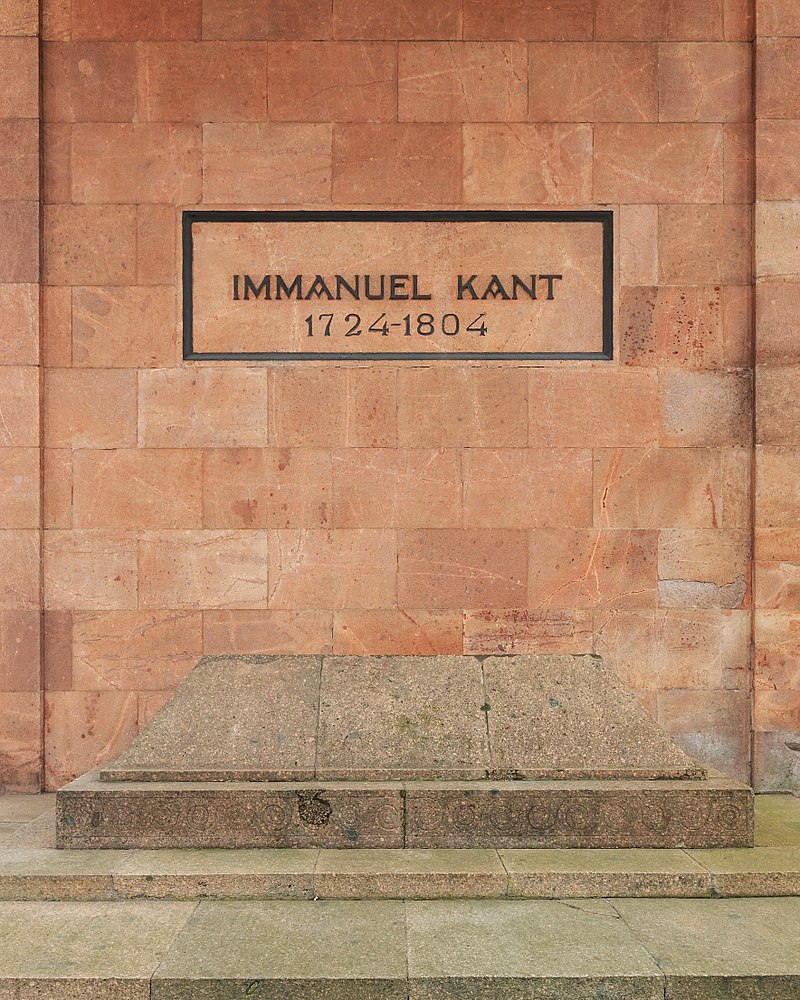

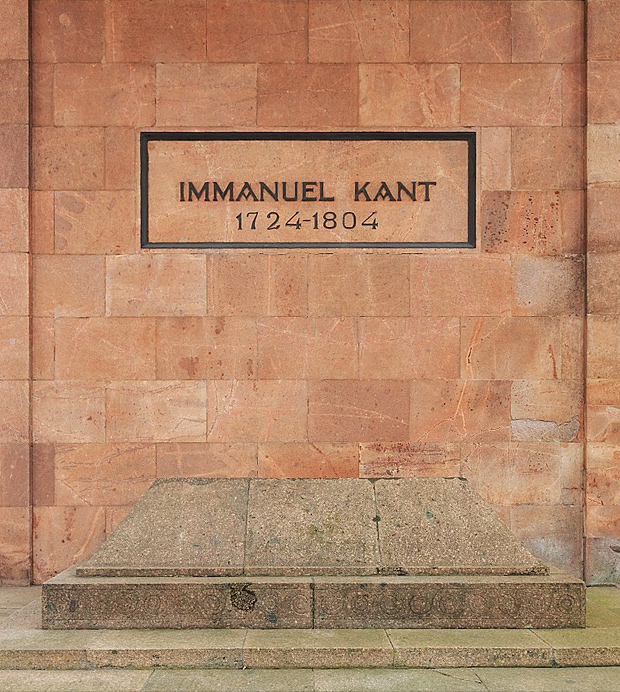

- Kaliningrad (Russia) - grave of Immanuel Kant and monument to Schiller.

- Brest (Belarus) - Polish inscriptions on the walls of buildings.

- Lviv (Ukraine) - Soviet officers at the monument to Jan III Sobieski.

Monument to the Polish king Jan III Sobieski, with the inscription “to King Jan III, the city of Lviv, 1898”, Gdańsk, Poland. Photos: Ania Skiendziel

Grave of Immanuel Kant, the German philosopher and founder of German classical philosophy, Kaliningrad, Russia. Photo: A. Savin. Public domain: Wikipedia

Monument to the German poet, philosopher and playwright Friedrich Schiller, in Kaliningrad, Russia. Photo: A. Savin. Public domain: Wikipedia

Polish words on the side of a building, Brest, Belarus. Photo: Rafał Turowski

Soviet officers pose near the monument of Jan III Sobieski in Lviv, autumn 1939. Photo: Unknown. © The Urban Media Archive of The Center for Urban History // Collection of Volodymyr Rumiantsev

Brainstorming

A brainstorming exercise begins in response to the photos. The teacher might ask questions such as the following:

- What can you see in the photographs?

- Why is a monument funded by the inhabitants of Lviv located in Gdańsk?

- Why are Polish words found on the side of buildings in Brest?

- Why is there a monument to a German writer in Kaliningrad?

- What explains these phenomena?

Explain that there are many similar cases e.g. the grave of the German philosopher Immanuel Kant in Kaliningrad (see above), German inscriptions in Gdańsk, e.g. in churches, etc.

The teacher writes the brainstorming results and answers on the board. There are no wrong answers. The teacher does not judge or comment.

NOTE: At the end of the lesson, the teacher might wish to come back and compare the students’ initial thoughts with the knowledge they have gained during the lesson.

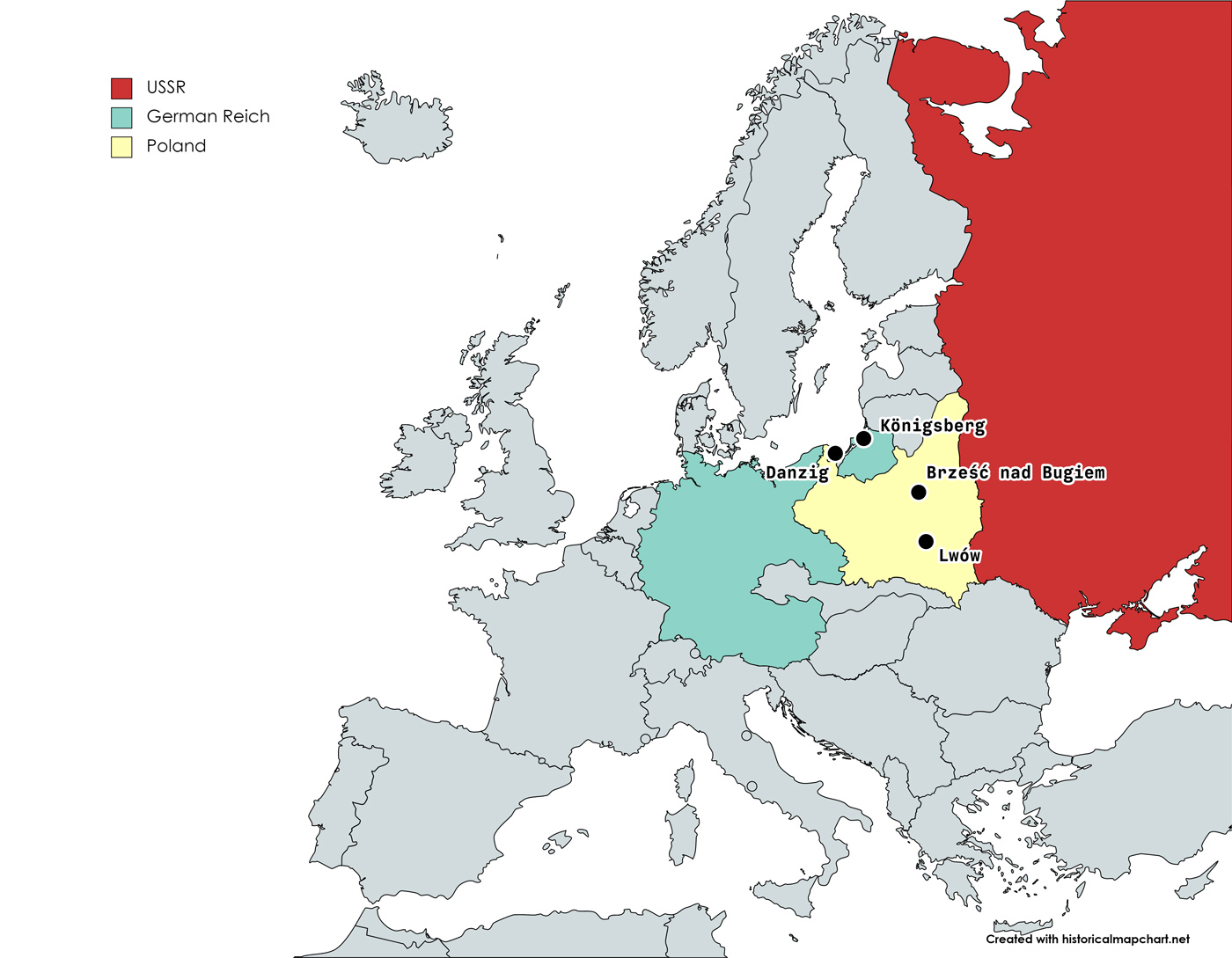

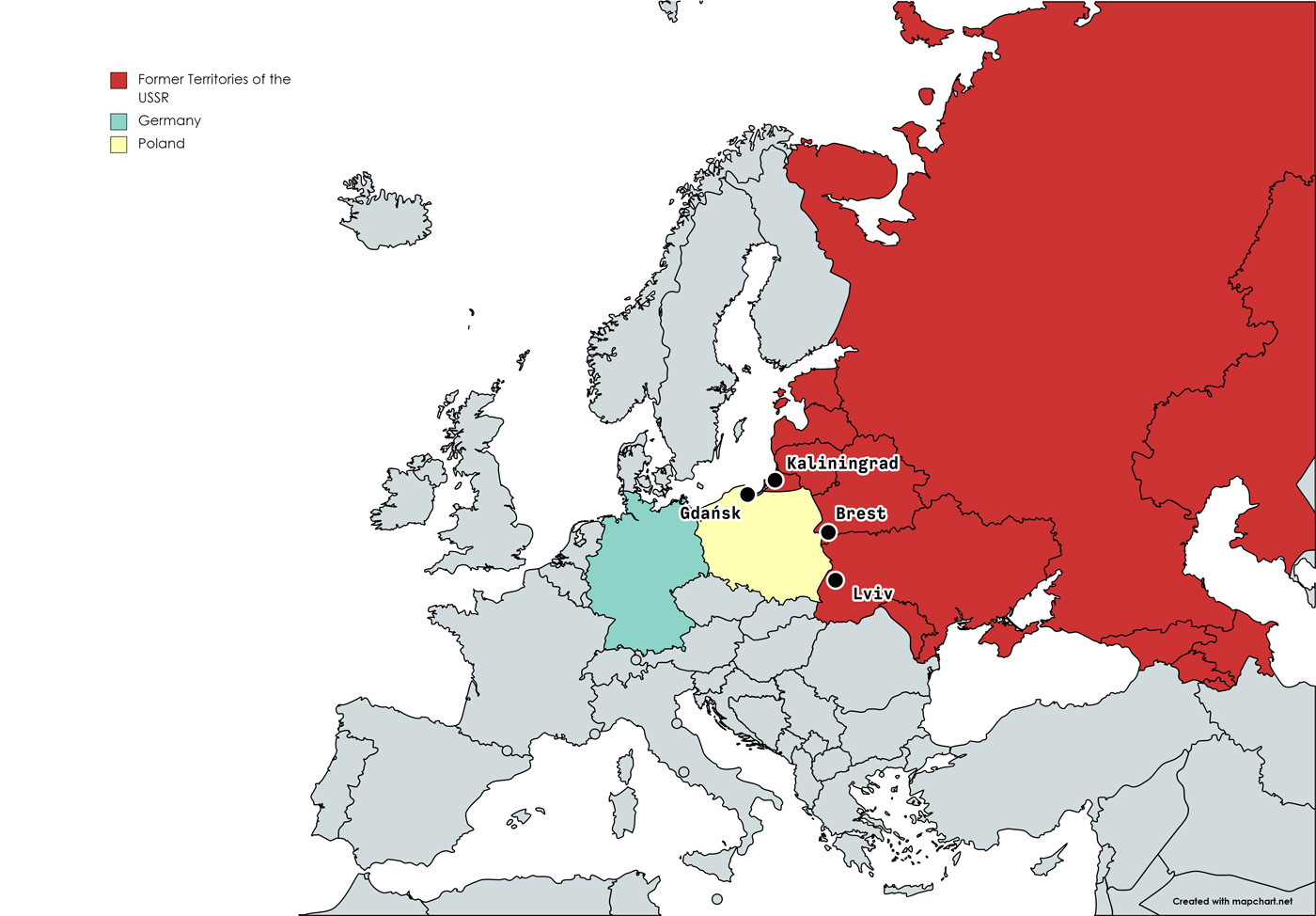

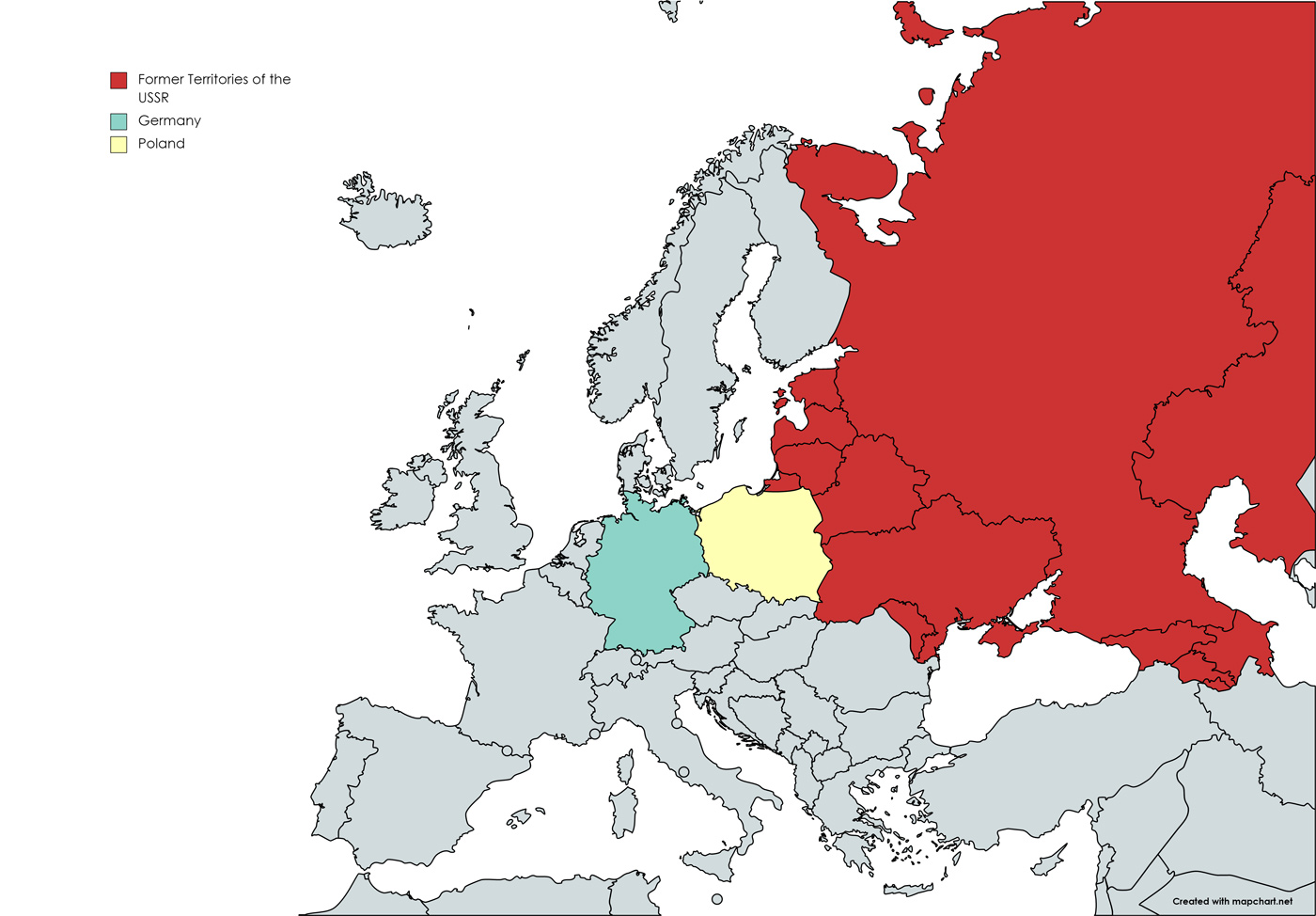

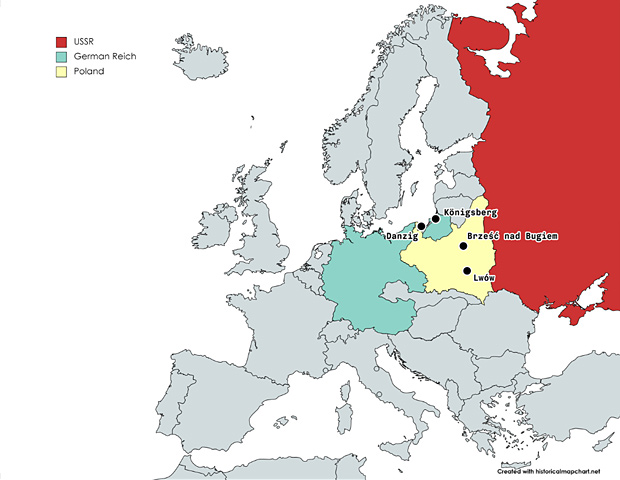

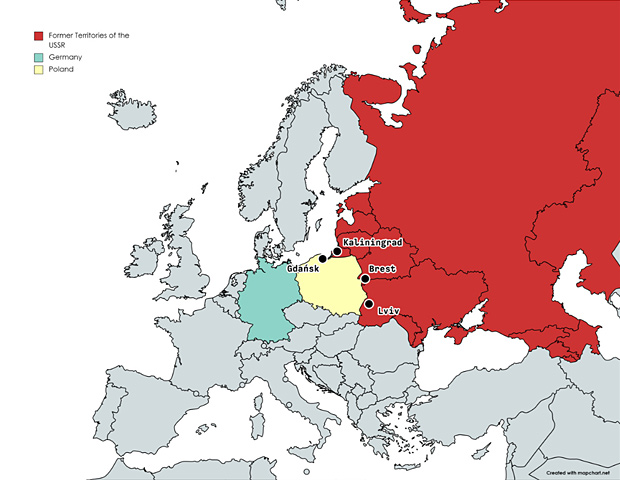

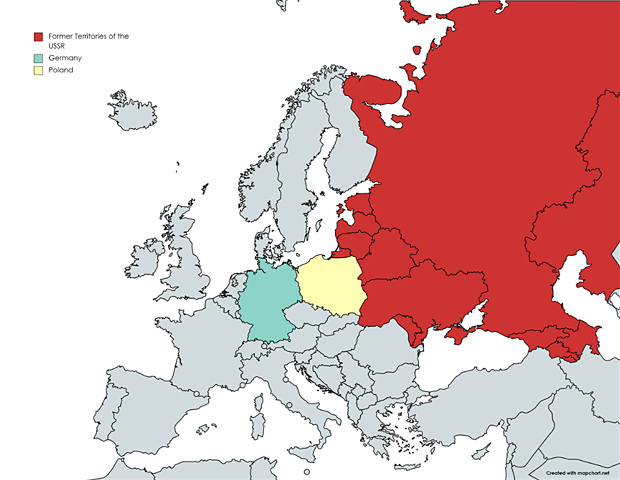

If the students mention border changes, or if the students are stuck and can’t think of any answers, it’s time to show the maps. Map 1 shows the borders and the locations of the cities before WWII; Map 2 shows the same cities but with the new, post-war borders.

Optional Exercise: The students look at Map 1 and try to identify which countries the cities will be in on a post-war map of Europe, before either being shown Map 2 or being asked to add the cities to Map 3 (a blank map).

Map 1

Map 2

Map 3

Part 2: Group work / Metaplan / Analysis of sources

30 minutes

Group work / Metaplan / Analysis of sources

After the brainstorming, the teacher explains the purpose of the main exercise. Four cities will be investigated during the lesson: Gdańsk, Kaliningrad, Brest and Lviv. Each of these cities (as the students will have noticed during the brainstorming session) belonged to one country before the war and another after it. Lviv used to be in Poland and is now in Ukraine, for example.

In this specific exercise, the students must use the information in the sources to first create a picture of how the cities looked before and after the war, and then “fill in the gap” with further information from the sources, from their own prior knowledge, or from assumptions, to work out how the changes occurred.

DIVISION into 4 groups

The teacher explains that the class will be working according to the Metaplan method. Each group is allocated one of the four cities identified during the brainstorming session. The teacher gives each group a set of resources for their allocated city. Students must analyse the sources and prepare to answer questions. Students should know that after they have prepared their answers, they will share them, and that there will be time for discussion and conclusions.

The teacher divides the students into groups and then distributes the sources (see Appendices).

Appendix III

Brześć nad Bugiem → Brest – Group 1 materials

Appendix IV

Danzig → Gdańsk – Group 2 materials

Appendix V

Königsberg → Kaliningrad – Group 3 materials

Appendix VI

Lwów → Lviv – Group 4 materials

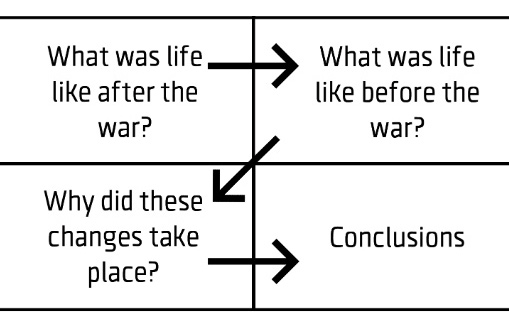

The teacher controls the group work, and gives help and support. If there is a problem, students can ask the teacher for help. Students can use laptops or smartphones (if available) to search for answers online. The students should discuss the following questions:

- What was life like after the war? Using the maps and sources, create a description of how people lived after WWII, what the cities looked like.

- What was life like before the war? Possibility analysis: create a description of what life in the city was like before WWII.

- Why did these changes take place? We are looking for reasons (e.g. war front, Operation Vistula, change of borders, displacement, deportations, repatriation, running from the Red Army or Wehrmacht, replacement).

The Metaplan table is displayed on the board so that students know what questions they have to answer.

After the first part of Part 2 (Group Work / Metaplan / Analysis of sources), there is a break (either a 5 minute break in the lesson, or the lesson ends at that point and the rest of the lesson, starting from the second part of Part 2— Answers/Presentations—can be done in another lesson). Students can reflect about what they have read and prepare to share the things they have learned.

20 minutes

Answers / Presentations

The teacher displays the Metaplan table so that it is visible to all: either using a projector or drawing the plan on the board. The teacher enters the students’ answers in the respective fields.

First, the teacher asks all groups to answer the first question (What was life like after the war?). The groups can be invited to answer in turn, e.g. Group 1, then Group 2, etc. The teacher then asks the students to answer question 2 (What was life like before the war?) Finally, the teacher asks for answers to the third question.

The teacher should write the groups’ answers in the individual fields so that all students can see them. This is essential for Part 3.

Parts 3: Discussion / Conclusions

20-25 minutes

The teacher starts the discussion by asking the following questions:

- What were the feelings of the people whose stories you have read?

- How did their lives change after the borders changed?

- Did the changes lead to the loss of the true “face” of the cities, or did they have any positive effects?

The teacher enters the conclusions in the last field.

At the end of the lesson, the teacher might wish to come back and compare the students’ initial thoughts with the knowledge they have gained during the lesson.

Give praise for a good job well done!

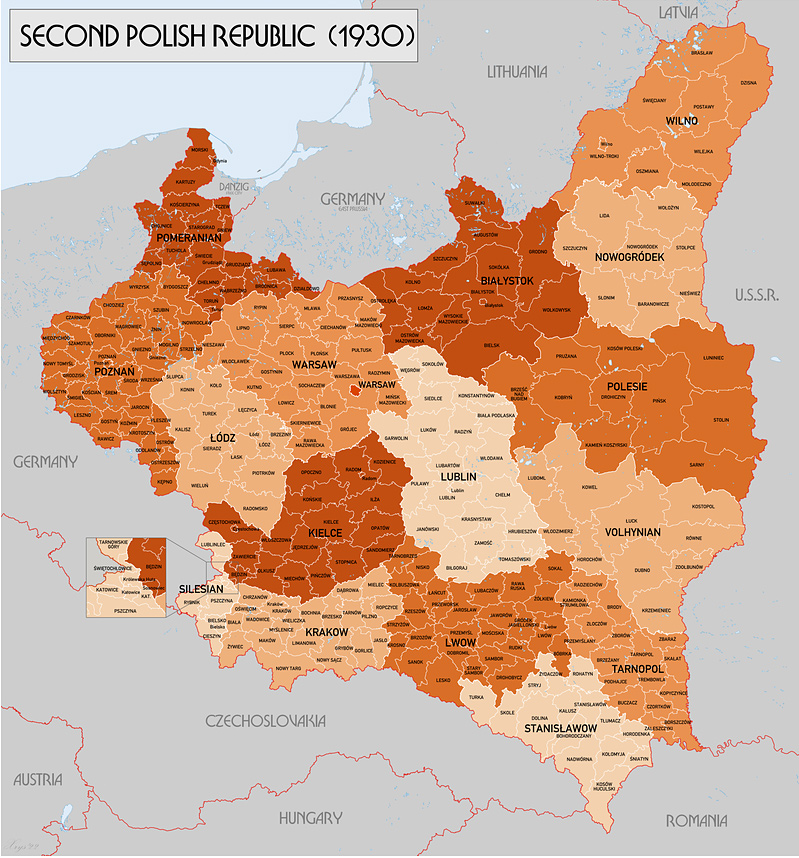

Appendix III: Group 1 Materials – Brześć nad Bugiem → Brest

Map of Poland in 1930.

Author: XrysD. Creative Commons license: Wikipedia

Map of the Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1939.

Панов, С. В. История Беларуси 1917 г. - начало XXI в.: учеб. пособие для 9-го кл. учреждений общ. сред. образования с рус. яз. обучения / С. В. Панов, В. Н. Сидорцов, В. М. Фомин: пер. на рус. яз. О. Р. Ермакович, В. М. Иванова. - Минск: Изд. центр БГУ, 2019. - 180 с.: илл.

Legend

State borders as of 1 September 1939

Place of the adoption of the law “On the incorporation of Western Belarus into the Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic” at the 3rd (extraordinary) session of the Supreme Council of the BSSR (14 November 1939).

Territories of Western Belarus and Western Ukraine annexed to the USSR in September 1939.

Borders of the USSR as of 14 November 1939

Territory handed over to Lithuania after the treaty of 10 October 1939 between the USSR and Lithuania.

Borders of the BSSR as of 14 November 1939

Place of the declaration of the resolution “On the annexation of Western Belarus to the BSSR” by the Western Belarusian People’s Assembly (30 October 1939)

Lithuanian region of Klaipėda (Memel Territory), occupied by fascist Germany on 23 March 1939

Memoirs

Pyotr K., born 1932 in Dubrava village, Brest district, Brest oblast

Before the war. We got on very well with our neighbours (the Shchur family). We often went to help them, and visited them in the evenings. Even though they were Poles. ... We had no conflicts among ourselves, everyone was united by the work on the land, there was no time to quarrel. Maybe others quarrelled with one another, to be honest, I don't remember.

After the war. I have already told you about my neighbours in Dubrava, the Polish Shchur family. They left the village in 1946. I don't know exactly why. They went to Poland, and a few years later Antoshka Shchur visited us and told us that they had settled on estates in Poland where Germans had lived during the war. Their lives are good, and they are happy to have settled in so well. After Antoshka's departure, I did not see my former neighbours again. That’s all.

Source: Brest State University (BrSU) Archive

Zdanevich A., born 1929, d. Arkady, Brest district, Brest oblast

Not far from Arkady was Pan Konyushevsky’s estate; the land now belongs to a monastery. He lived in Warsaw, and managed the estate through an estate manager. Pan had about 30 hectares of garden, a large cowshed (with space for 50 – 70 animals), a pond, a small park, a manor house, and houses for hired workers. When the Soviets came to power, Pan Konyushevsky was on the estate. Three or four activists came onto his land, put him against the wall, and were about to let him have it. But one of the activists was a good man, and they took pity on Pan, fired a shot at the ceiling, and let him go. Pan made his way to Poland illegally. His estate was confiscated, and his cattle were shared out. But in 1941, the war began. Pan Konyushevsky returned to his estate a month and a half after the Germans occupied our village. He called those men who had wanted to arrest him, and told them his terms: ‘I’m not looking to get my own back on you, let that be on your conscience, but I do ask you to return the cows and everything else you confiscated.’ Some of the confiscated cattle had already been destroyed, including the dairy herd, but between 10 and 15 cows were returned to him. He sold them and left for Warsaw in Poland, for good.

Source: Brest State University (BrSU) Archive

Appendix IV: Group 2 Materials - Danzig → Gdańsk

Poland’s population balance (1939-1950). Note: figures are approximations.

Piesowicz, Kazimierz. Demographic effects of World War II. [Demograficzne skutki II wojny swiatowej.] Studia Demograficzne, No. 1/87, 1987. 103-36 pp. Warsaw, Poland.

| Description | Total | Poles | Jews | Germans | Others (Ukrainians/ Belarusians) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population 1939 | 35,000,000 | 24,300,00 | 3,200,00 | 800,000 | 6,700,000 |

| Natural Increase 1939-45 | 1,300,000 | 1,000,000 | 300,000 | ||

| Transfer of German population | (760,000) | (760,000) | |||

| Deaths due to German occupation | (5,670,000) | (2,770,000) | (2,800,000) | (100,000) | |

| Deaths due to Soviet occupation | (150,000) | (150,000) | |||

| Population remaining in the USSR | (7,800,000) | (1,000,000) | (100,000) | 0 | (6,700,000) |

| Emigration to the west | (480,000) | (280,000) | (200,000) | ||

| Population gained from Recovered Territories | 1,260,000 | 1,130,000 | 0 | 130,000 | 0 |

| Re-immigration 1946-50 | 200,000 | 200,000 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Natural increase 1946-50 | 2,100,000 | 2,100,000 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Population 1950 | 25,000,000 | 24,530,000 | 100,000 | 170,000 | 200,000 |

Interview with Sylwia Bykowska from the Institute of History of the Polish Academy of Sciences

Immediately after the war, there was no other city in the entire area of the Recovered Territories in which Poles settled in such numbers and as willingly as in Gdańsk. The words Gdańsk and Westerplatte did not sound ‘foreign’; in a sense, they signified the ‘promised land’. The city became purely Polish for the first time in its history. Eventually, about 15,000 of the original inhabitants remained there. (...)

How big was the population, and what were the percentages of Poles and others in Gdańsk immediately after the end of the war?

The numbers were fluid, of course, because it must be remembered that the end of the war set in motion the machinery of peoples’ migration. Thousands of people started travelling in all directions. The make-up of Gdańsk’s population changed in just a short time. Poles were arriving en masse, and the Germans were leaving, often under duress. In 1945, even before the transports organized by the State Repatriation Office (pursuant to the Potsdam Agreement), there were so-called military displacements. The Germans were forcefully removed from their homes. In July alone, we know that three such actions took place, as a result of which about 10,000 people left Gdańsk. Germans. It is estimated that from June to October, about 60,000 Germans were displaced from Gdańsk in such actions, carried out by the Polish Army with the support of the UB and the MO. This was about half of the German population living in Gdansk when the Polish administration came to the city at the beginning of April 1945. It seems that troops surrounded entire streets, or even whole blocks of the city, and removed the inhabitants. Everything according to the principle: “Pack your bags, everyone can take hand luggage only, the train is already waiting”. They were removed because more and more Poles were arriving with nowhere to live. These were the decisions of the new local authorities.

At the end of the 1940s, who lived in this Polish Gdańsk, which had been transformed by the war? Is it true that even the majority of Gdańsk families at that time had borderland roots?

Not really ... In 1948, Kresowiacy and the Bug River inhabitants constituted 16 percent of the population. More than 60 percent were newcomers from central Poland, including about 14 percent from Warsaw and Mazovia. And it must be said that there was no other city in the entire area of the so-called Recovered Territories where Poles settled in such large numbers and as willingly as in Gdańsk.

Source: Gdansk.pl, Wiosna 1945 - rodzi się polski Gdańsk. Rozmowa z Sylwią Bykowską z Instytutu Historii PAN, https://bit.ly/32G9F8P, last visited 27.12.21

Tales from a demolished city: Gdańsk in 1945, seen through the eyes of children

Alfons Flisykowski, the commander of the defense of the Polish Post in Gdańsk, was murdered by the Germans. His daughter, Henryka Flisykowska-Kledzik, was 9 years old in 1945.

“My mother was allocated a room in an apartment in Siedlce, rather than an apartment of her own. Two German women lived there, and one of them - the younger and more attractive one, Frida, had a friend who came to see her regularly. He was a Russian soldier. That made the apartment safe. Mother knew that when she came home from work, she would not find other tenants there, except for the German women.” - said Flisykowska-Kledzik.(...)

Over time, people from different parts of Poland, including Greater Poland, Kashubia and Lviv, moved into the tenement house where the Flisykowski family lived. “I don’t remember any animosities or quarrels. We were all in the same position; we all came with one suitcase or bag, and we helped one another. One lady made us clothes, another, through friends, got us eggs. The atmosphere was very good,” recalls Flisykowska-Kledzik.

Source: Dzieje.pl, Opowieści ze zburzonego miasta, czyli Gdańsk w 1945 r. w oczach dzieci, https://bit.ly/3qvAYLh, last visited 27.12.21

Fragment of a hand-written letter from Hermann Fischer from Horn, East Prussia, to a friend - 28 November 1946

“Then came 11 November, a Sunday, and with it our expulsion and deportation from our homeland. The previous day, Saturday, the Poles had made an inventory and robbed us of all our usable clothing. We went to the collection point with 20 pounds of hand luggage each, were registered, and taken under armed escort to Sonnenborn, where our Polish office was located. We had to stay there for two days, and after being searched and robbed again, we were forced to march to the railway station in Mohrungen. We arrived in Mohrungen in complete darkness and were dead tired. The town was almost completely in ashes. Poles surrounded us and attacked and robbed us. We arrived at the transport train (about 45 cattle cars for 4,500 people). There were 116 people in my wagon. We had no chance of a seat, or even standing room. We sat one on top of another. The Poles robbed us again of what little we had, and the train started moving, but it soon stopped again, somewhere on an open track or on the dead track of a railway station. We suffered another eleven days of being robbed non-stop. ...”

Source: Josef Henke (1995), ‘Exodus aus Ostpreußen und Schlesien: Vier Erlebnisberichte’, in: Wolfgang Benz (ed.), Die Vertreibung der Deutschen aus dem Osten: Ursache, Ereignisse, Folgen. (Frankfurt/M: Fischer Taschenbuch), pp. 123-5.

Memories of Anna Sobko, who was displaced to the village of Smołdzino near Słupsk, in Pomerania

From a report by Anna Sobko, entitled “One from Rus, another from Prussia, and the devil has brought you all together!”. The “Wisła” (“Vistula”) action and settlement in Pomerania, as recalled by former residents of Zahoczew.

“We came to Poland after the war. The Sejm (Parliament) could not reach a decision, and [it was eventually decided to] bring us here, to the West, because we are of Ukrainian origin, to mix us up. People were already living under the Russian system, the commune. We were deported [from Zahoczew] in [19] 47 and came here. (p. 308)

[I feel at home now], now I do. Already [I have grown up] children and grandchildren. I already have nine great-grandchildren! I already have my roots here. But I always cry, mostly at night when I can’t sleep, when I remember how it was. [In Bieszczady], we were unified, and [people] respected each other very much. We were all locals, not brought in [from all over the place]. But here, Novak the priest came out and said: “Yes, one from Rus, another from Prussia, and the devil has brought you all together!” And it’s true. Everyone had a different style. We got used to it eventually, but before that it was very hard. And I’ve been living here since 1947. If only our home were there [in Bieszczady] ... Yes, and later, in the 1960s, the first Orthodox churches were built, in Słupski and Bytów.” (p. 330)

Source: Anna Sobko (2017) ‘“Jeden z Rus, drugi z Prus, a wszystkich was diabeł na kupę zwiózł!”: Akcja „Wisła” i osiedlenie na Pomorzu we wspomnieniach dawnej mieszkanki Zahoczewia, opracowanie Piotr Zubowski’, Wrocławski Rocznik Historii Mówionej Rocznik VII, pp. 305 - 342. Google Books.

Appendix V: Group 3 Materials - Königsberg → Kaliningrad

Arrival of migrants to Kaliningrad in 1947.

Photo: Unknown. Public domain:

State Archive of Kaliningrad Oblast

The first echelon with a group of immigrants from the Moscow region is sent to Kaliningrad, September 1946.

Photo: G. Zelma. Public domain: Ogonyok magazine.

Historical centre of Königsberg after 2 RAF air raids, August 1944.

Photo: Fritz Krauskopf.

Public domain: Wikipedia.

Memories of Soviet immigrants to Kaliningrad

Anatoly Plyushkov, born in 1922, living in the Kaliningrad region since 1947

All of us, party workers from Leningrad, were traveling on the same train. Most of the party members sent to the region were single, including me. (...) Everyone’s mood was upbeat. Two phrases stick in my mind, things my fellow travellers said that most clearly show the way we were thinking. One girl, I don’t remember her name, who was also being sent to the Kaliningrad region on party business, said: “I can’t shake the feeling that we’re going to the past.” And it’s true that most of us war survivors felt that we were bringing with us the advanced Soviet culture and way of life. Europe seemed to us a backward and hostile region of capitalism. The prospect of bringing Soviet culture to East Prussia was very attractive. At the same time, we knew almost nothing about the place where we were going to be working. And a young officer who was traveling with us remarked: “A Russian soldier, arriving in Europe, won’t notice that he’s not at home.” We considered the newly-acquired Kaliningrad territory not as someone else’s, but as land that we needed to bring under control. We were full of optimism, and no task seemed too hard for us to manage.

Valentina Korabelnikova born in 1935, living in the Kaliningrad region since 1946

I have only vague memories of the move itself—nothing special happened—but I do remember an incident at the railway station. I was left sitting on a suitcase (at that time everyone had one or two suitcases, mainly the things we needed most), and someone came up to me and said: “Little girl, you’re sitting on my suitcase. Get up, I’m taking it now.” I got up, and he took the suitcase and left. That’s how the whole family lost all their things.

...I saw Germans, real, live Germans... You can understand ..., there’d been the war, and we’d been told that the Germans were very bad—that they were “not humans”. (...) What a shock — they turned out to be ordinary people, just like us.

Elbrus Belyaev, born in 1926, living in the Kaliningrad region since 1947

When I arrived here, I saw a professor of botany at the University of Konigsberg, who was walking around the Botanical Garden, wiping away tears, saying goodbye. He said: “I have given my whole life to this garden. This is one of the best gardens in the world.” It was true. The garden was very well maintained and beautiful. There were unique trees from all over the world. Our people did not appreciate this treasure. (...) So the man who had looked after the garden was gone, and with him the care the garden needed. In short, all cultural and natural values began to die.

Source: Meduza, «Зашла немецкая семья, просили хлеба» 70 лет назад Кенигсберг стал Калининградом: воспоминания переселенцев, https://bit.ly/3EA2FYq, last visited 27.12.21

Extract from a top secret order of the Minister of Internal Affairs of the USSR

“1. The head of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Kaliningrad Oblast, Major General Demin, is to resettle 30,000 Germans from the Kaliningrad Oblast to the Soviet zone of occupation in Germany: 10,000 in October 1947, and 20,000 in November 1947.

First to be resettled are Germans living in the city of Baltiysk and near the Baltic Sea coast. From other regions in the oblast: German families not able to work and not engaged in socially useful work, German children who are in orphanages, and elderly Germans living in homes for the disabled are also to be resettled.

Resettled Germans are allowed to take with them personal property up to 300 kg per family; they may not take items and valuables prohibited for export by customs regulations.”

Source: Yuri V. Kostyashov (2002), East Prussia through the eyes of Soviet immigrants: The first years of the Kaliningrad region in memoirs and documents. (St Petersburg: Belvedere), p. 272.

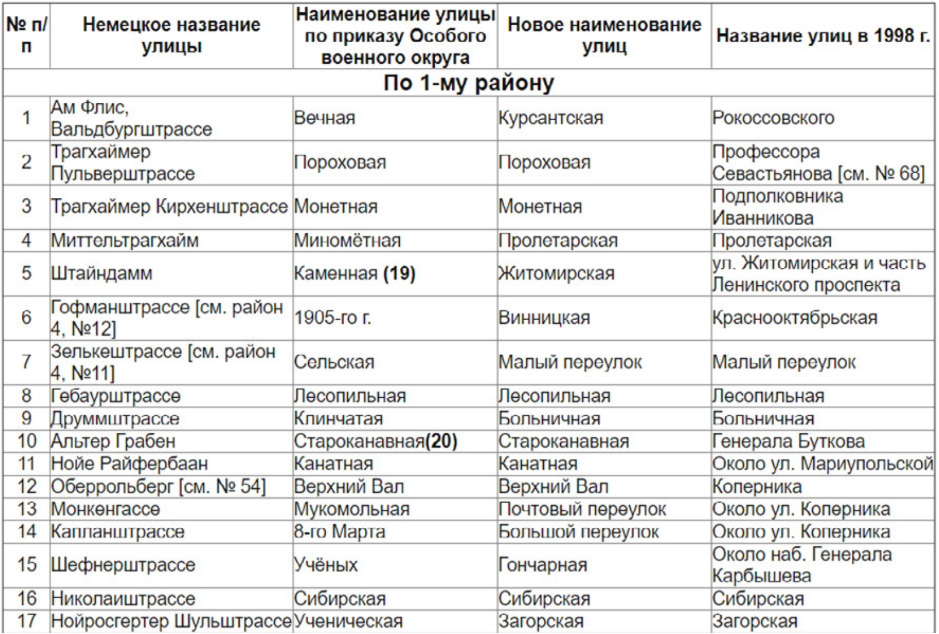

Changes to place names in Kaliningrad

Source: Klgd.ru, Топонимия Калининграда, https://bit.ly/3HiCIyf, last visited 27.12.21

English translation

| German street name | Street name upon creation of the Special Military District, 1945-6 | New street name | Street name in 1998 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Am Filz, Waldburgstraße | Vechnaya | Kursantskaya | Rokossovsky |

| Tragheimer Pulverstraße | Porokhovaya | Porokhovaya | Professora Sevastyanova |

| Tragheimer Kirchenstraße | Monetnaya | Monetnaya | Podpolkovnika Ivannikova |

| Mitteltragheim | Minometnaya | Proletarskaya | Proletarskaya |

| Steindamm | Kamennaya | Zhitomirskaya | Zhitomirskaya |

| Hoffmanstraße | 1905 goda | Vinnitskaya | Krasnooktyabrskaya |

| Zelkeschstraße | Selskaya | Maly Pereulok | Maly Pereulok |

| Gebauerstraße | Lesopilnaya | Lesopilnaya | Lesopilnaya |

| Drummstraße | Klinchataya | Bolnichnaya | Bolnichnaya |

| Alter Graben | Starokanavnaya | Starokanavnaya | Generala Butkova |

| Neue Reeferbahn | Kanatnaya | Kanatnaya | Mariupolskaya |

| Obberolberg | Verkhny’ Val | Verkhny’ Val | Kopernika |

| Monchengasse | Mykomolnaya | Pochtovy Pereulok | Kopernika |

| Kaplanstraße | 8 Marta | Bolshoy Pereulok | Kopernika |

| Stefnerstraße | Uchenych | Goncharnaya | Generala Karbysheva |

| Nikolaistraße | Sibirskaya | Sibirskaya | Sibirskaya |

| Neurosgerter Schulstraße | Uchenicheskaya | Zagorskaya | Zagorskaya |

Appendix VI: Group 4 Materials - Lwów → Lviv

A fragment from the diary of Lviv citizen Alma Heczko, 18 May, 1945

“We are leaving tomorrow. This is our last evening in Lviv. I’m writing in the dining room, on the chest. A storm is approaching; I can hear distant thunder. For our last walk, we went to the High Castle. It is green and wonderful, and there are “candles” on the chestnut trees; it is so beautiful here in May. I love this little place so much; I used to come here almost every day. And today I’m looking at the High Castle for the last time. I will never be able to come back here again.

Outside, it’s raining and windy, and I can see lightning. Everyone is asleep, and I’m writing about every little thing. I’ve lived here for 24 years. I was born in the room where my daughter is now asleep. And now I have to get out of here. We are being expelled from our native land”.

Source: Center for Urban History, Lviv, The lost home: post-war forced relocations, https://bit.ly/3mvYA1p, last visited 27.12.21

Native languages of Lviv citizens

Source: R.M. Lozinskiy (2005), Ethnic composition of the population of Lviv (in the context of social development of Galicia). (Lviv), p. 358

| Language | 1931 | 1959 | 1970 | 1979 | 1989 | 2001 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ukrainian | 11,3% | ~55,5% | 65,2% | 71,3% | 77,2% | 88,8% |

| Russian | 0,1% | ~38,5% | 31,1% | 25,7% | 19,9% | 9,7% |

| Yiddish | 24,1% | ~1,2% | 0,7% | 0,3% | 0,2% | 0,01% |

| Polish | 63,5% | ~2,8% | 1,4% | 0,9% | 0,6% | 0,4% |

| Others | 1,0% | ~2,0% | 3,7% | 3,0% | 2,9% | 1,1% |

Population of Lviv in 1900-1989

Source: G. Bodnar (2010), National Relations In Lviv In The 1950s And 1970s Through The Eyes Of Rural Migrants. (Lviv), p. 314

| Nationality | 1900 | 1931 | 1940 | 1941 | 1942 | 1943 | 1944 | 1951 | 1959 | 1970 | 1989 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ukrainians | 19,9% | 15,9% | 22,0% | 22,0% | 26,1% | 29,9% | 26,4% | 42,8% | 60,2% | 68,2% | 79,1% |

| Russians | - | 0,2% | 1,6% | - | - | - | 5,5% | 30,8% | 27,1% | 22,3% | 16,1% |

| Jews | 26,5% | 31,9% | 32,8% | 25,4% | 15,6% | - | 1,1% | 7,0% | 6,3% | 4,4% | 1,6% |

| Poles | 49,4% | 50,4% | 43,4% | 50,3% | 54,0% | 62,9% | 66,7% | 16,3% | 3,9% | 2,5% | 1,2% |

Interview with V. H., whose family settled in Lviv in 1945

“At the end of the war, my father was serving on the First Ukrainian Front. His unit made its way through Belarus and Poland. It was rumoured that there were many vacant apartments in Lviv. [...] They stopped at a place where some acquaintances lived, and my father saw an announcement saying “Firewood for sale”, stuck on a post in the road, at the Rohatka. This was a code: it was not firewood that was for sale, but an apartment [...].

The Pole was one of those who did not have time to leave in 1945. The family living in the apartment was going away and leaving the apartment, so he was happy to get at least some money. There was a nice bed there, an iron lattice bed... And that stove – a green, light one. So we stayed there.”

Source: Center for Urban History, Lviv, New Lviv residents and their city, https://bit.ly/312BVSJ, last visited 27.12.21

Other Lesson Materials

The beginning and end of World War II

Children in World War II

Remembrance and memorialisation of World War II in different countries

Young people and forced labour during World War II

Consequences of World War II

Video: Clash of Memories