This website uses different cookies. We use cookies to personalise content, provide social media features, and analyse traffic to our website. Some cookies are placed by third parties that appear on our pages. You can find more information and options to choose from in our Privacy Policy and Configurations for usage.

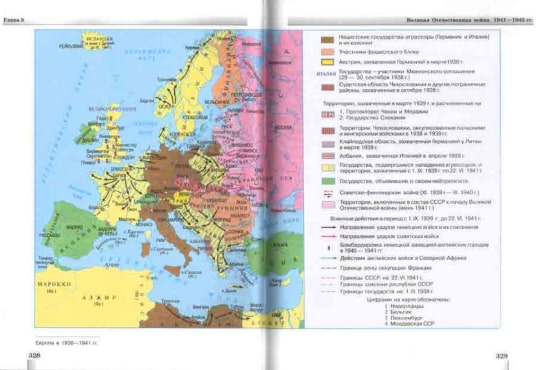

The exhibition “Different Wars” reveals the differences in the narration and perception of the history of World War II in modern high school textbooks of the Czech Republic, Germany, Italy, Lithuania, Poland and Russia.

The choice of the subject is evident: World War II remains one of the most painful and conflicting episodes of the European nations’ memories. In Russia the victory in the Great Patriotic War is one of the most important pages of national history.

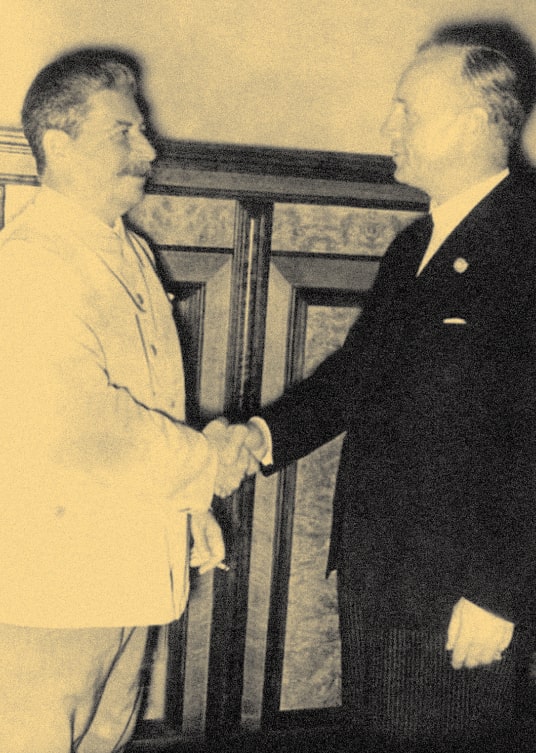

The German - Soviet Treaty

Moscow, 23 August 1939

In Germany the treaty is known as the Hitler-Stalin Pact, in other countries as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

Bild 183-S52480 / CC-BY-SA 3.0

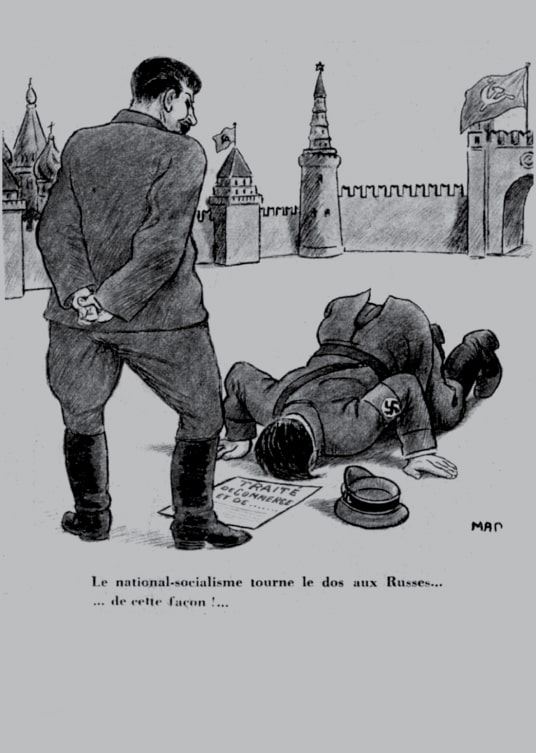

Italy: Astonishment and indignation

The world welcomed the announcement of the treaty between two regimes that were on opposite sides from an ideological point of view with a mix of astonishment and indignation (Giardina, p. 351).

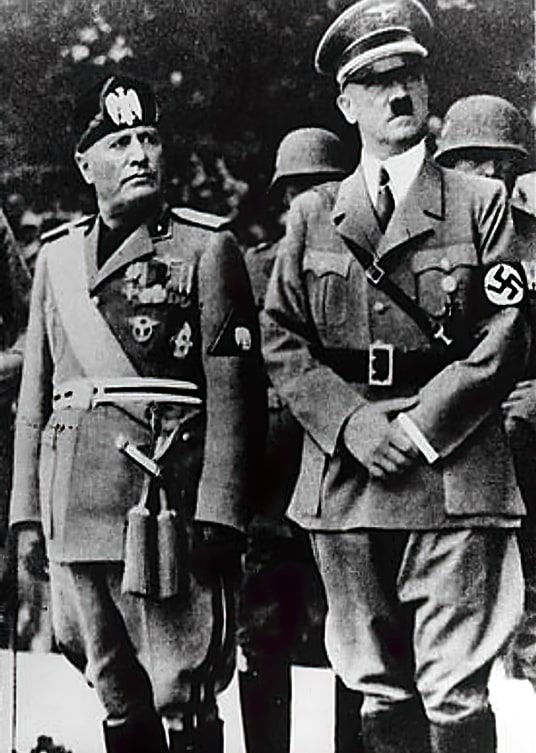

Banti shows the relations between the treaty and the general diplomatic situation: In April 1939, France and Great Britain guaranteed to the Polish government their will to help Poland in case of a German attack. Germany makes its counter-moves. In May 1939, Germany and Italy sign the “Pact of Steel” […] insufficiently reassuring for the Germans. […] Counting on the tensions between the USSR and the Western powers (the latter have not accepted the Soviet proposal of a common participation to an eventual anti–Nazi war) the German and Soviet diplomats started negotiations that led — causing general surprise — to the signature of a “non-aggression treaty” between the USSR and Germany on the 23 August 1939 (p. 439).

It has to be stressed that both textbooks give little attention to the reasons that led the USSR to sign a treaty with Germany. Only Giardina speaks about the Soviets’ surprise when the “Operation Barbarossa” began in 1941.

Russia: “Forced Move”

All Russian textbooks give the same interpretation of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact as a forced step taken by Stalin in fear of finding himself in international isolation. In order to free his hands to launch his aggression against Poland, Hitler decided to neutralize the USSR. Stalin, having lost faith that it was possible to make a treaty with Great Britain and France, but being convinced of the proximity of an imperialistic war, ventured upon a collusion with Hitler (Volobuyev, p. 78).

The Soviet-German non-aggression treaty was a forced step by the USSR after all its initiatives on organising a joint rebuff to the aggression had run into the solid wall of opposition of the Western politicians of the time (Plenkov, p. 92).

Only two modern textbooks mention the fact that the Soviet party concealed the ‘secret protocols’: Soviet authorities blankly denied the fact of making a secret agreement with Germany, although its text was available for foreign scholars (Zagladin, Kozlenko, p. 209). None of the authors mentions the fact that the Soviet Union gave economic and military aid to Germany (although this information was present in the textbooks published in the 1990s)

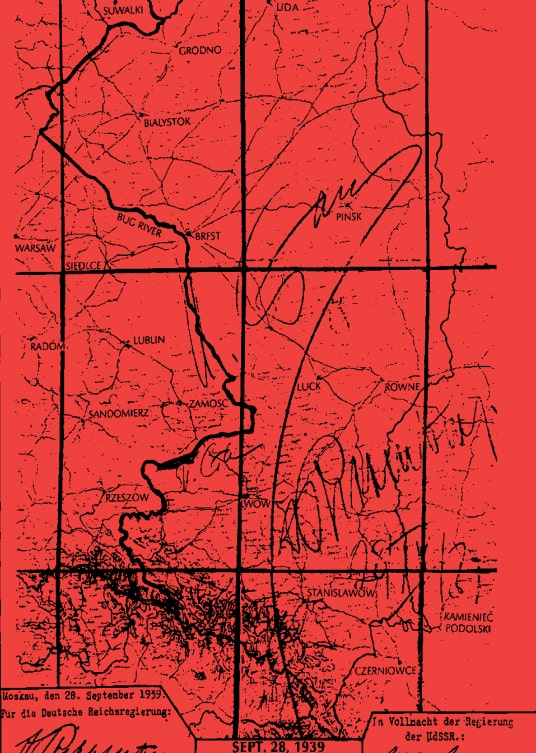

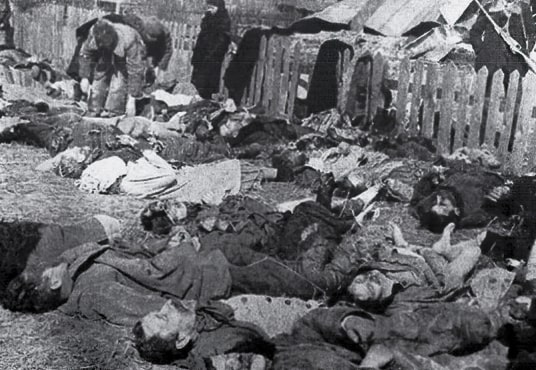

The signing of the secret protocol decided the fate of the Baltic States […], as well as Poland, Finland and Bessarabia. According to the official statement, this [Polish] population was ‘being protected’ by the Red Army. Tens of thousands of Polish officers were taken prisoner. In the spring of 1940, about 22 000 of them were executed in Katyn (near Smolensk), near Kharkov and Ostashkov (near Tver) by NKVD "secret police" troops, upon the decision of the Politbureau (Izmozik, Rudnik, p. 192–193).

Traditionally, the textbooks dispel the myth of Stalin intending to attack Hitler first. The fact that the signing of the treaties led to the war is one of the most painful spots of the ‘official’ memory.

Characteristically, the style of narration changes in these accounts in most textbooks. Instead of a dry and concise citation of facts, their authors go in for lengthy speculations aimed at reconstructing Stalin’s logic.

Germany: Evaluation from different perspectives

The authors present the facts and interpret the intentions of the two dictators: Hitler wanted to avert a twofront war and dissolve the Polish state with the aid of Stalin. Stalin suspected the Western powers would intentionally direct Hitler’s expansionism against the Soviet Union. After the destruction of Czechoslovakia, Stalin demanded that all Eastern European countries beyond Poland should be protected from Germany. The Western powers considered this demand to be Soviet hegemonic ambition and refused. Stalin concluded the pact with Hitler to find time for their own armament (Klett, p. 248)

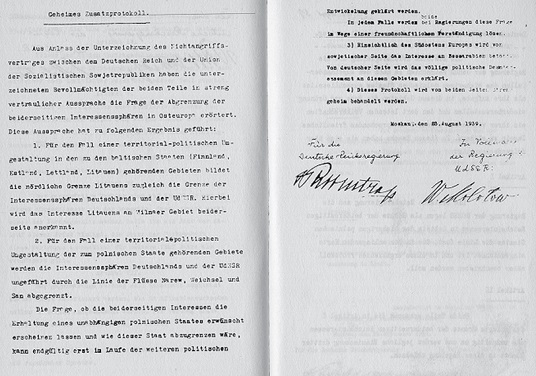

In Klett the text of the contract as well as the secret protocol can be found (p. 245, 246). Students are asked to evaluate it from the perspective of Hitler, Stalin, the Polish people as well as the Western powers.

Poland: The fourth division of Poland

In Poland, the German-Soviet non-aggression treaty is also known as the “Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact”. Special attention is paid to the secret protocol attached to the Pact (quoted in its entirety in textbooks as source material), whereby the territories of Poland were ‘divided’ between the two countries. The secret protocol is regarded as a key document to an understanding of the course of the war. It also serves as a proof of the cynical game played by the USSR which at the first phase of war matched that of the Third Reich’s as enemies and aggressors.

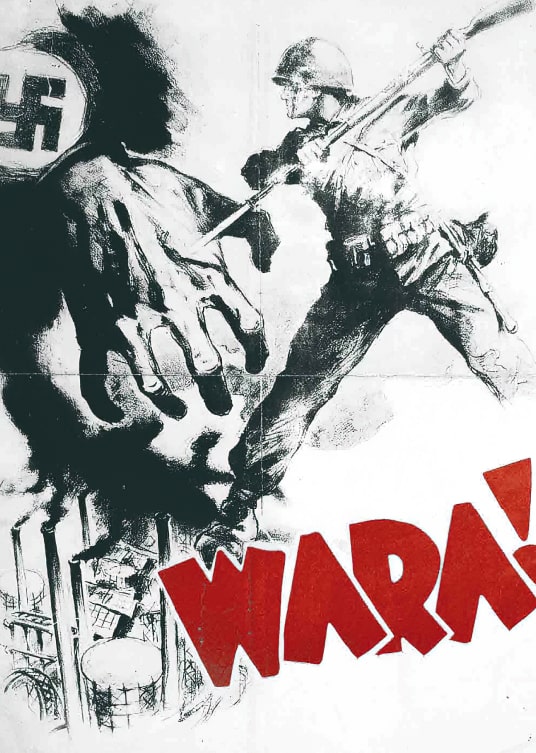

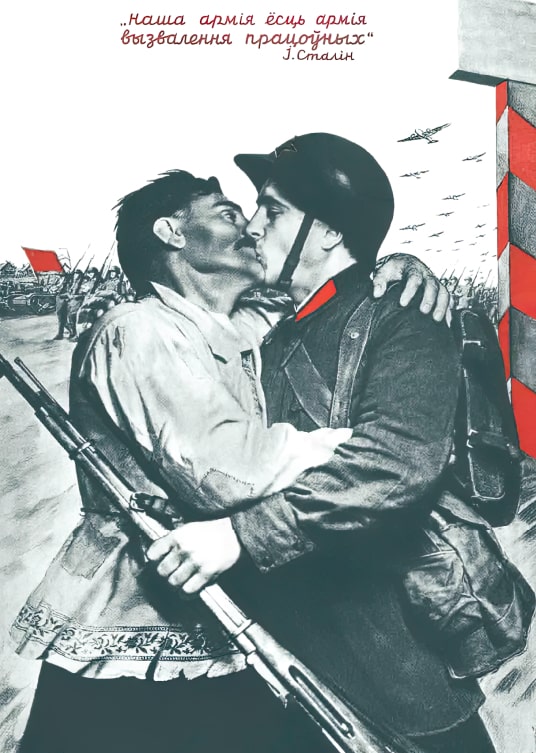

The German-Soviet Pact signalled yet another partition of Poland. […] The Soviets also carried out an annexation of Poland although they did so under the pretence that it was carried out at the ‘request’ of the peoples of the conquered lands. […] Widespread, aggressive propaganda presented the occupation as a friendly act, enslavement as liberation and criminal acts as the meting out of justice (Stola, p. 50).

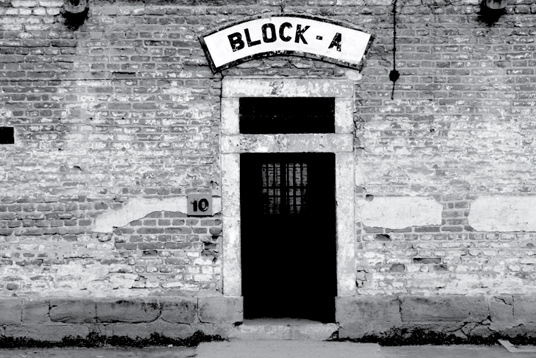

The Holocaust

Some textbooks treat the Holocaust as a main topic, whereas others reduce the relevance of the Jewish victims.

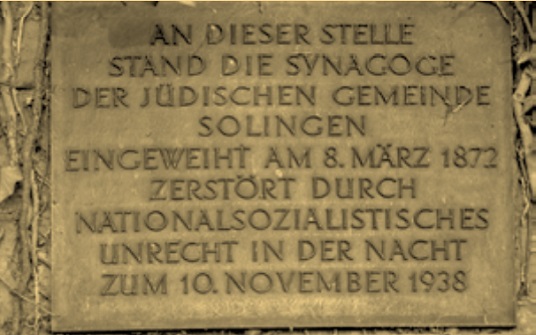

Germany: Unprecedented crime in world history

The Holocaust […] marks the singular character of the crimes committed by the Nazi regime in the history of the world (Schöningh 1, p. 398).

The Holocaust is an essential subject in all textbooks. They describe the ideological causes of the genocide, the system of extermination camps, the mass exterminations, the bureaucratically organised industrial murder. They focus on numerous groups of perpetrators, who have been involved in the genocide alongside the SS. The indifference of the majority of Germans is mentioned critically.

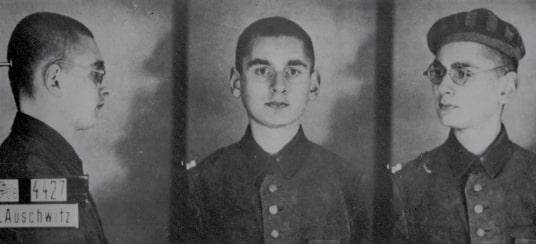

The sources convey the concrete reality of the organised terror in the extermination camps: power hierarchies, forced labour, violence and death, selection procedures, as well as mass exterminations (Schöningh). They confront the report of one of the survivors of the massacre in Babi Yar with the memories of the chief commander of Auschwitz Rudolf Höß giving a cold-blooded description of the extermination of Jews in the gas chambers (Klett).

Students are asked to make an analysis and evaluation of the reasons of the Holocaust based on texts by historians and sociologists.

Lithuania: The question of participation

In Lithuanian school textbooks a large part is dedicated to the persecution of the Jews and the Holocaust. Tamošaitis’s textbook for the 12th grade provides in detail the reasons for the persecution of local Jews during the occupation: a) presence of a criminal element; b) revenge for some crimes during the first years of Soviet occupation; c) contradicting geopolitical interests of Jewish and non-Jewish Lithuanians (supporting either the Soviet Union or Germany); d) Anti-Semitism which had grown due to favourable conditions of war and Nazi occupation; e) fascist and Nazi ideas which had become especially strong before the war. It is important to stress that it was not the locals who determined the tragic fate of Jews. Nazi Germany is to blame for the war (p. 188).

The main Holocaust perpetrators are named. For Lithuania, it is Joachim Hamann who led a squad of “Flying Slaughterers” (German: Rollkommando). It is also worth mentioning that only one Lithuanian “Jew killer” is named in Baltos Lankos textbook. In Lithuania it is still a very sensitive issue, and the names of Lithuanian co-perpetrators in history textbooks rarely provided.

Czech Republic: The Holocaust is out there

The Czech textbooks describe the Holocaust as a horrifying novelty, often quoting the book of Zygmunt Baumann, “Modernity and Holocaust”. They tell the story of the marginalisation of compassionate instincts as one of the effects of society’s bureaucratisation, industrial development and modern technologies. In these textbooks, the Holocaust is happening somewhere else, predominantly in Poland. The only connection with Czech lands is the concentration camp in Terezín (Northern Bohemia), a station from which the Czech Jews were deported further to the East (Kuklíkovi, p. 109). So the Holocaust story in the textbooks is not perceived as a story that concerns Czech memory and political culture.

Italy: Collective responsibility

The textbooks indicate the SS chiefs promoted the “final solution” of the Jewish question, describe the deportations and everyday life in the camps and conclude with a description of gas chambers and crematories.

Moreover Banti includes an in-depth analysis about the Holocaust. He critically investigates the reasons for the tragedy and discusses the terminology that is used to talk about the historical event: Holocaust, Shoah, genocide.

The critical pages put the emphasis on the “ordinary men” that took part in the genocide. They show that the main reason for the extermination was not the desire to free space in the East for the “Germanic race”, but to carry out a radical elimination of the Jews.

Poland: Victims, betrayers and perpetrators

The systematic exclusion of Jews from public life is described in great detail: from the revocation of civil rights through the tragedy of the ghettos to the “final solution” in death camps such as Auschwitz-Birkenau, Sobibor or Treblinka.

Extermination is analysed within a wider context, as the result of “Hitler’s ideology”. Poland’s place is seen as very specific — in view of the number of Jews living here before the war and the number of Polish Jews who were murdered. It was in Poland that the Germans established 400 ghettoes and death camps. Extermination accounted for 5.5 to 6 million people, i. e. twothirds of the European Jews, and 3 million of those murdered were Polish Jews.

The slightest help offered to Jews in Poland could lead to capital punishment or collective penalties. The textbooks also describe the fact of “szmalcownictwo” — the blackmailing of Jews who were in hiding and their betrayal to the Germans. For a single Jew to survive the German occupation, it involved the help of many — usually dozens — of people. And yet just one “szmalcownik” could cause the death of many Jews (Stola, p. 45).

The participation of the Poles in the pogrom of Jedwabne, which is still controversially regarded in Poland, is also mentioned, although it is shown as a unique incident.

Russia: Jews or “Soviet citizens”?

The Holocaust is seldom described or even named in Russian history textbooks. In their accounts of the occupation regime the authors unanimously emphasise that ethnic purges in Eastern Europe were targeting Jews and Slavs equally. Very seldom Jews are singled out as a specific group of victims.

Danilov, Barsenkov et al. describe Jews as being amongst the victims of the occupation policy: Overall, 13.5 million of Soviet citizens (excluding war prisoners) were purposefully exterminated by the Nazis and their accessories in occupied territories. […] Amongst these casualties about 3 million Jews fell victims of the Holocaust (p. 391).

Plenkov describes the persecution as such: The Nazi criminals designed and implemented a bureaucratic machine to exterminate people based on their race, an unprecedented event in human history. […] Antisemitism was a cornerstone of the National Socialist ideology. The persecution of Jews began with declaring a boycott on 1 April 1933. A systematic extermination of this nation took place in 1939–1945 (p. 77–78).

Special Emphasis on Victims of War

All textbooks place special emphasis on war victims, supporting varying national narratives.

Germany: “Subhumans” and political opponents

Victims of the Second World War

| German soldiers killed in action | 3000000 |

| German soldiers missing in action | 1300000 |

| German civilians | 500000 |

| German losses due to expulsion and deportation | 2250000 |

| Japanese soldiers | 1200000 |

| Japanese civilians | 600000 |

| Chinese and Southeast Asian forces and civilians | unknown |

| US soldiers | 229000 |

| Western Allies | 610000 |

| Civilians of Western Allies | 690000 |

| Soldiers of the East and Southeast European countries | 1000000 |

| Soldiers of the East and Southeast European countries | 8000000 |

| Soviet soldiers | 13000000 |

| Soviet civilians | 6700000 |

| Victims total (about) | 55000000 |

Other victims of the Nazi-Regime is a sub-heading in the chapter The Genocide on European Jews (Klett, p. 264). Students learn: The victims of the Nazis were not only the Jews but also up to 500000 Romanies, as well as the Slavic peoples, especially Poles, Czechs and Russians, who were regarded as “subhumans” in the Nazi classification (Klett, p. 264—265).

Around one million Russians and Poles were killed by so-called task forces of the SS (Schöningh 1, p. 398). About three million members of the Red Army died in camps for prisoners of war (Klett, p. 257).

Plenkov describes the persecution as such: The Nazi criminals designed and implemented a bureaucratic machine to exterminate people based on their race, an unprecedented event in human history. […] Antisemitism was a cornerstone of the National Socialist ideology. The persecution of Jews began with declaring a boycott on 1 April 1933. A systematic extermination of this nation took place in 1939–1945 (p. 77–78).

As a result of the war, citizens of other European countries were also deported to concentration camps. As a rule, these Europeans, as well as many Germans, were political prisoners (Klett, p. 264—265).

Italy: The war against civilians

Giardina claims that the main victims of the Second World War were the civilian population and the Jews: The most horrible and cruellest persecution was against Jews. [...] They were deported to prison camps (German: Lager) often located in Poland and Germany, whose names have become infa- mous (Auschwitz, Buchenwald, Dachau and many oth- ers) (p. 361).

According to Banti, the main victim was the civilian popula- tion in all countries: The numbers [...] suggest that this is a war against civilians and not only a war between armies (p. 456). Banti also mentions the oppression of the Polish people by the Soviet Army and the Nazis. Banti stresses the deporta- tions from Eastern Europe: During the war from these areas [...] 13.5 million people were recruited as forced labourers or deported (8million civilians, 4 million prisoners of war, 1.5 million Jews), (p. 457). Banti pays great attention to the topic of post–war vengeances, with a particular attention to women.

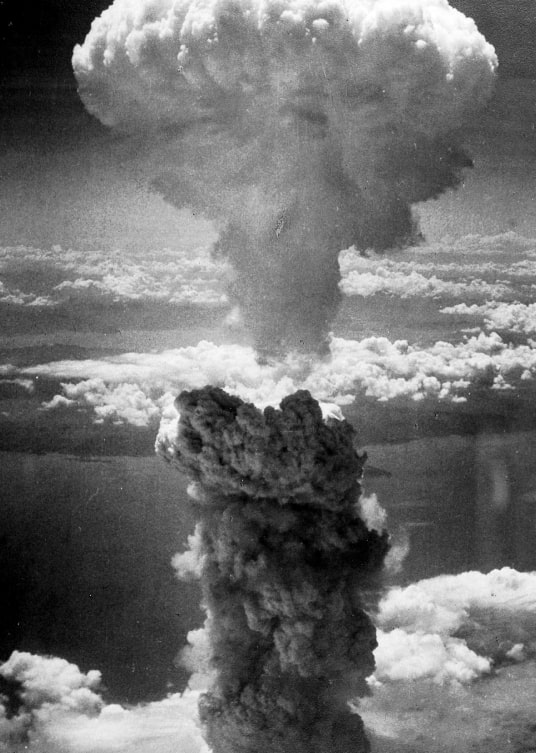

Another interesting fact is how the two textbooks deal with the war in the Pacific: Banti stresses the hard occupation by the Japanese army: The population of the occupied territories is more brutally exploited than under the Western colonial domination (p. 449). Giardina emphasises the first atomic bombs, with the testimony of a Japanese survivor from Hiroshima.

Czech Republic: Victims of two occupations

In Czech textbooks, victims of the war genocide were not only Jews and Romanies, but people from Baltic states as well. After the annexation of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia to the USSR in 1940, a persecution started there focusing on a purging of the anti-Soviet forces which concerned not only members of democratic parties, but their family members including children. It was not a political suppression, it was a nation’s elimination (Válková, p. 41). The Soviet occupation was a shock for the locals; therefore this experience is presented as a reason why these countries joined the German side. After the second occupation by the USSR in 1944, persecutions were even more severe.

But there are other groups of victims mentioned, especially amongst civilians. The longest paragraphs are dedicated to the bombing of Dresden. Victims of Nagasaki and Hiroshima are described with remarks that the use of atomic bombs was due to the acceleration of the war and an opportunity to try a new weapon.

Russia: Tragedy as “price of Victory”

Soviet combat losses

| Textbook | Total losses | Combat losses |

|---|---|---|

| Izmozik, Rudnik | 27 000 000 | 115 00 000 |

| Kiselyov, Popov | 27 000 000 | 9 200 000 |

| Levandovsky, Shchetinov | 27 000 000 | 11 400 000 |

| Zagladin, Kozlenko | 27 000 000 | 12 000 000 |

| Danilov, Barsenkov, Gorinov (ed. Filippov) | 27 000 000 | 86 49 500 |

Almost all national history textbooks recommended by the Russian Ministry of Education attribute the information on the losses in the chapter to “the price of Victory”. This partially removes the issue of responsibility for the colossal death rate of civilians, soldiers and prisoners of war.

The absence of validated official data on human losses during the war or on its consequence leads to discrepancies in the numbers (the textbooks’ authors use different calculations by historians)

All textbooks mention the German policy towards Jews (from one sentence to two paragraphs), quoting the total number of the Holocaust victims, Sinti and Romanies (usually just mentioned), Slavs (quoting details of Generalplan Ost). Victims among the population of territories occupied by the Wehrmacht and its allied troops are usually mentioned in passing. The victims of the forced labour are reduced to one sentence.

The population was subjected to restrictions, was deprived of many rights, was taken to work in Germany by force, often fell victim of ethnic persecution. All resistance attempts were suppressed (Plenkov, p. 111).

All National History textbooks mention the victims of Soviet repressions: Soviet citizens, deported ethnic groups. Many textbooks also mention victims in the republics and territories annexed in 1939–1941.

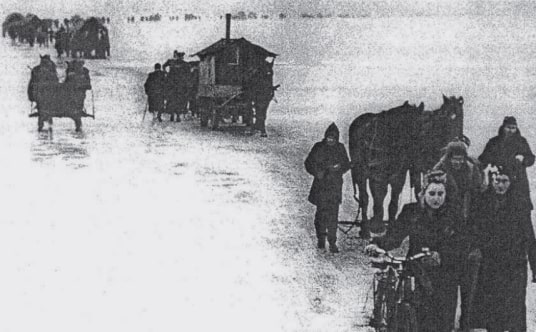

Forced Migration and Deportation

Different groups of migrants and deportees are depicted – depending on the countries’ experience and perception of history.

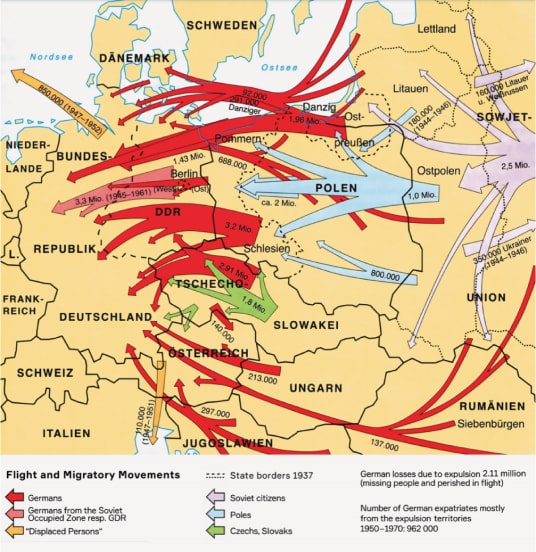

Germany: Flight, expulsion, integration

The theme “Flight and Expulsion” is not explored in the text - books. They inform about the most important facts: the refugees fled from the advancing Red Army in 1944–1945 or from Polish and Czechoslovakian units. Those who were forced to leave their homeland in eastern Germany and neighbouring settlements, according to Article 13 of the Potsdam Agreement, were called “expellees”. The Poles who had been expelled by Germans before returned to their homelands. Those who were forced to leave their homeland in eastern Poland, now Soviet territory, were resettled to the former German provinces. The integration of refugees and expellees is referred to as one of the greatest post-war achievements of the German society.

Between 12 and 15 million Germans had to leave their homes in eastern Germany and the neighbouring settlements.

Russia: Crimes of Stalinism

Russian History textbooks mention ethnic deportations in the USSR and in occupied territories mostly in association with Stalin regime policies. Among the forcibly displaced peoples, they mention the Poles, the Germans, the Chechens, the Ingush, the Balkars, the Kalmyks, the Karachays, the Crimean Tatars, the Kurds, the Meskhetian Turks and the Greeks.

It is a well known fact that some of the “small” peoples were “punished” because some of their representatives had collaborated with Nazi occupation authorities. In 1943 and 1944, the Kalmyks, the Karachays, the Chechens, the Ingush, the Balkars and the Crimean Tatars were deprived of their status as nations and were displaced from their native territories. In August 1941, the same fate had befallen the Volga Germans (Levandovsky, Shchetinov, p. 216).

Most textbooks call deportations a crime of the Stalin regime. However, there are textbooks that do not at all mention the deportations that affected millions all over the country.

Czech Republic: “No place in our country”

At the end of the war, German-speaking people were expelled from their homes in a disorganised manner accompanied by acts of violence. These actions were not only immediate reactions to the end of the 6-year occupation and to the information about the Nazi atrocities, brought by people returning from concentration camps, but they were also acts of personal revenge and an effort to become rich by stealing property (Válková, p. 47).

Nevertheless the expulsion is presented matter-of-factly as a part of the war events. Readers are to gain the impression that after the experience of the Nazi occupation, a peaceful coexistence of Czechs and Germans in one state was not pos - sible anymore. The collaboration of some of the Sudeten Germans (K.H.Frank, K.Henlein) with Hitler served as an argument for the application of the principle of collective guilt. Only one of the textbooks describes the “death march” of 25 000 German citizens of Brno to the Austrian border.

Directly after 1945 a period of “wild expulsion” started. Despotism and mass violence was a “tax” charged for nations’ hatred against Germans. However, the hatred (that could be understood taking into account the very particular Czech experience) has affected Czech political culture in a clearly negative way and showed a dark side of the Czech democracy (Kuklík, p. 127).

Poland: Mass deportation under inhumane conditions

On 28 September 1939, while the German and Soviet invaders were still engaged in combat with the remaining Polish units, the Third Reich and the USSR signed a friendship treaty. The treaty introduced new borders, thus partitioning Poland.

In the lands directly annexed to the Reich, the Germans began to carry out their systematic ethnic policy. At this time, approximately 900 000 Poles were deported. Most of them were assigned to the territory of the German General Government, whilst others were sent to the depths of the Third Reich as forced labourers. […] The settlement of some 360000 German colonists brought here from territories belonging to the USSR, the Baltic States and Romania was intended to ensure swift Germanisation of these Polish territories (Roszak, Kłaczkow, p. 182).

Prisons filled up with crowds of suspects and accidental victims — in total, more than 100000 people were arrested. And yet more — over 320000 — fell victim to mass depor tation into the very depths of the USSR. […] Thousands of deportees, particularly children and frail people, did not survive the many days of long travel in inhumane condi tions (Stola, p. 51)

After the war Stalin and the Communist authorities in Poland were intent on creating an ethnically homogenous state. Approximately 3 million Germans were expelled from the territories of the “Regained Lands”, while 300000 Ukraini ans, 36000 Belorussians and several thousands of Lithua nians were deported from the border territories in the East to the USSR (Roszak, Kłaczkow, p. 230).

Consequences

The Yalta conference resulted in the political partition of Europe and marked the beginning of the Cold War. The controversy surrounding this event is presented differently across Europe.

Germany: At the centre of Allies’ conflict

The decisions of the conference of Yalta are considered a compromise initially concealing the clash of interests between the Western Allies and the Soviet Union. After the war, however, they led to the division of Europe. In particular the territorial reorganisation of Europe relating to Germany and Poland posed a potential for conflict. With the expulsion of the Polish population from eastern Poland, the USSR had already altered the political landscape before the Potsdam Conference.

When interpreting the causes of the conflict, the authors show both the perspective of the USA and the USSR: The military and economically dominant United States were interested in creating a free world market and in establishing a global peace and security system. The Soviet Union had been extremely weakened and partially destroyed by the war.

They wanted to protect their spheres of influence by satellite states that they dominated and at the same time compensate their economic losses by dismantlement (Klett, p. 408).

The result of the reorganisation after the war: the United States and the USSR became the leading global powers. France and England were no longer able to pursue world power policies (Schöningh 2, p. 12).

Poland: Ally without the right to vote

Throughout the years of war, Poland stood on the side of the Allies and yet, when it came to establishing a post-war order, Poland was excluded from the decisions concerning its fate. Border changes in Poland became the currency of negotiation in talks with Stalin.

As Soviet victories multiplied, and the Germans were pushed out of Eastern and Central Europe in 1944, the importance of the USSR in international relations increased, while that of the Republic of Poland diminished. […] Roosevelt and Churchill had already agreed that the USSR would have to be rewarded for its enormous contribution to the war with Hitler, and Stalin made no secret of his appetite for the territories he had occupied in 1939. […] In exchange for the lands occupied by the USSR, Poland was to be given the former German lands which lay to the east of the Oder and Neisse Rivers. The Polish Government in London was not even informed of this decision (Stola, p. 67).

Polish textbooks emphasise the drama Poland experienced after the war: although victorious, it was abandoned by the West and fell into dependence on the USSR. The Eastern Borderlands, with Vilnius and Lviv, areas of importance for the Polish culture, were lost.

Czech Republic: How the country became the East

The main presented geopolitical consequence of the war is the change of the political map of Europe. This change concerns mostly Eastern Europe and is described as a forced arrangement, yet there is clear denial of the “myth of Yalta” that the division of Europe was negotiated in advance. The textbooks focus mostly on who was present at which conference, stress the very last one in Potsdam where the Allies approved the expulsion of Sudeten Germans from the eastern territories.

The war is presented as the starting point for division of Europe by the Iron Curtain. Since then the Czechs fell into the sphere of eastern influence; therefore we all should be aware of how this happened (Válková, p. 33). The occupation of the Czech lands sets the foundation for the remembrance narrative, which focuses on victimhood

Lithuania: Triumph of “the Soviet dictator”

The 12th grade textbook published by Baltos Lankos writes about the consequences of WWII accentuating the Soviet Union’s aggressive politics: What are the most important consequences of this war? First, Nazi Germany, fascist Italy and Japan have been destroyed. […] It may seem a victory of democratic forces over dictatorial aggressors. But the victory was mostly determined by the Stalinist Soviet Union which before and in the beginning of the war had as many predatory goals as Hitler’s Germany (Tamošaitis, p. 205–206).

The textbook for the 12th grade published by Briedis points out the crimes committed by the communist USSR

In 1940 the NKVD 'secret police' killed about 26000 Polish citizens in Katyn and other cities of the USSR under a special Politbureau decision. […] About 1.5 million Poles and Balts were exiled to Siberia in the summer of 1941. During the war between the USSR and Germany whole nations were falsely accused of collaborating with the Nazis and exiled […]. After the Red Army crossed the borders of the USSR, it often behaved not like a liberator, but like an occupant prone to rob and abuse civilians (Kapleris et al., p. 147).

Italy: End of an old order

Giardina stresses the fact that the end of Second World War also brought an end to the European supremacy, substituted by two new superpowers, the USA and the USSR. A new bipolar international balance of power was established. The creation of the UN (1945) was the most important result in the attempt of creation of a new international order capable of preventing new conflicts (p. 398).

The hostilities did not end in Europe and Asia and the contrasts in the approach to peace between the two major winners were already emerging. The United States, having an overbearing economic supremacy and fewer losses caused by the war paid more attention to the reconstruction and the establishment of a stable world order than to the punishment of the losers. The USSR, having suffered tremendous losses and devastation, thought about the price of victory in political, economic and defense terms (Giardina, p. 381)

As is well known, another war, an “atomic war” as people say after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, could be the last war for all. […] During 1946 the leaders of the two alliances openly accused each other that they would not respect the treaties signed during the war and that they would create their areas of influence (Banti, p. 490).

Russia: Survival amid loses

Russian textbooks name the collapse of Hitler’s regime and the formation of the bipolar world the greatest political consequences of the war. They mention the foundation of the UN and the system of international law, the Nuremberg and the Tokyo Trial. Among social consequences, they name the colossal numbers of victims in European countries, first and foremost, in the USSR, and the demographic consequences associated with that. Another grave consequence they name is the general devastation.

The vast losses of the Soviet Union were caused by the purposeful policy of the Nazis intended to completely destroy the Russian sovereignty and people. A sad role was played by the fact that Soviet political and military leaders often unnecessarily wasted the lives of their compatriots (Levandovsky, Shchetinov, p. 224).

The victory in the Great Patriotic War proved that the model of state and society, which was created by the Bolsheviks, in spite of everything proved viable and that it was a well-coordinated mechanism, which was in the condition to defend itself at the cost of enormous losses (Izmozik, Rudnik, p. 239).

Remembrance

Although both the victims and the postwar reconciliation process are emphasised, they are at times eclipsed by narratives focusing on national heroes and triumphs.

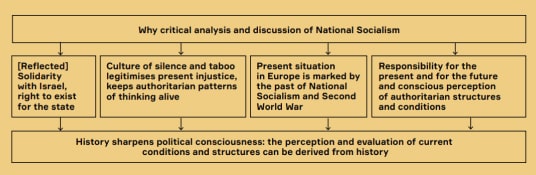

Germany: Culture of remembrance and responsibility

The discussion about the unprecedented break with civilization by Nazi Germany is a fundamental subject in all German textbooks, not only in history. The guiding questions used are focussing on the issue: What role does the Nazi past play in the present? Klett gives a summary of the most important answers (p. 409):

Klett presents material that corresponds with the students‘ reality. The schoolbook shows how a German secondary school system dealt with its Nazi past.

Lithuania: Torn between Soviet and German repression

Stories about the Soviet deportation of Lithuanians in 1941 and the burning-down of whole villages during the Nazi occupation, has a special place in the school textbooks and Lithuanian public memory. Examples are given in the textbooks, like the punishment for the actions of Soviet partisans in 1944 when the Nazis burned down Pirčiupiai village with all its 119 residents — including babies and old people.

The textbooks also mention people who tried to save people persecuted by the Nazis.

A picture published in Bakonis‘ 10th grade textbook deals with the remembrance process: it shows the German Chancellor Willy Brandt kneeling in front of the Warsaw ghetto monument. The students are asked to judge Brandt’s gesture, also in order to develop their own system of values (p. 108).

Italy: Omission of remembrance

In the textbooks, remembrance days and memorials dedicated to the victims of the war are not mentioned. The official remembrance day in Italy is 25 April: on that day the National Liberation Committee (CLN) proclaimed the general insurrection against the Nazis. However, the fact that Italy proclaimed this day as the Commemoration day of the Liberation is not mentioned in the textbooks, neither in text nor images.

The textbooks do not deal with the topic of denazification in Germany. At the same time nothing is said about the way the new democratic Republic of Italy dealt with the difficult fascist legacy. The topic of how the post–war debates between the antifascist parties influenced the culture of remembrance is also missing.

Czech Republic: “Brave resistance and ingenious sabotage”

The occupation of the Czech lands sets the foundation for its national memory, which focuses on the assumption of a Czech victimhood. Therefore, the main subjects, events and figures of memory presented in the textbooks deal with the resistance and the burnt-out villages.

The Czech resistance is presented as a role model for the students, something they can be proud of — a ‘ray of light’ in the ‘darkness of the war’. That is why jokes about the occupation period are printed as well as stories about the witty Czechs organising acts of sabotage. The authors also mention the favourite saying “PP — pracuj pomalu!” meaning “work slowly” — to undermine the efficiency of the German regime.

The extermination of Lidice and Ležáky is probably the most remembered event of the Second World War, often used in cinema and literature. Problematic issues like the collaboration are not directly mentioned or remembered. The Munich Agreement serves as a general excuse: the feelings of inferiority weakened liberal and democratic elements within the Czech society and prevented a different, more courageous or less cooperative approach.

Russia: Unnamed but not forgotten

The memory of the Second World War is scarcely covered in Russian history textbooks. A rare exception is a mention of the ‘people’s memory’, which retains the names of commanders and heroes of the war (Kiselyov, Popov, p. 143). At the same time, pictures play an important role. All the textbooks contain the iconic images of the most well-known Soviet monuments and paintings about the war. Through them, students are supposed to learn about the most significant symbols of the war and the Soviet victory.

Poland: Heroism in national tragedy

.jpeg)

In the Polish national memory, the beginning of the war is historically linked with the partitions of Poland in the 18th century. The German and Soviet attack led to the ‘Fourth Partition’ of the country: It kept alive the idea of a ‘lonely Poland’ resulting from the oft-bemoaned military passivity on the part of the Western Allies.

The heroism of the Polish soldier during the September Campaign is glorified particularly in the light of the technological inferiority of the Polish army. It is ranked as equivalent to later military campaigns such as the Warsaw Uprising and the service of Polish soldiers in the British army, especially the Royal Air Force. The Battle of Westerplatte, with which the beginning of the war is associated, and the sign of anchor — Fighting Poland, referring to the Polish Underground State and their fight, are also symbols of heroism. The concentration camp at Auschwitz and the Katyn massacre stand for the tragic annihilation of the Polish elite and are sites mentioned in every school textbook.

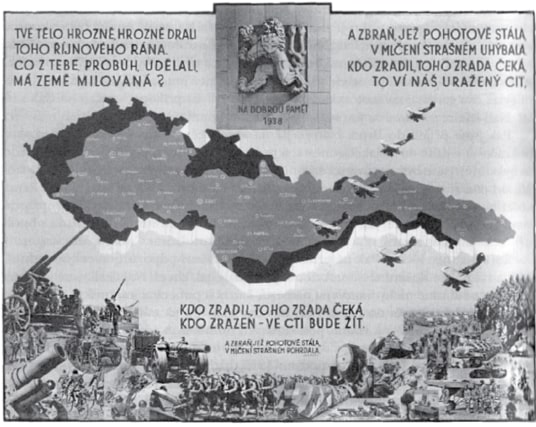

Czech Republic

Events of September 1938 shook Czech society…

The Munich Agreement — Czech society traumatised

The Munich Agreement was signed on 30 September 1938 by representatives of Great Britain, France, Italy and Germany, who agreed that Czechoslovakia must cede to Germany portions of Czechoslovak territory along the country’s borders populated by Germans. Representatives of Czechoslovakia were present in Munich, but were not invited to take part in the actual negotiations. This is how the Munich Dictate is presented to the readers, an event which is essential for the understanding of course of the war in Czech lands. The “Munich Dictate”, often called simply the “betrayal”, is used to account for the apathy of the Czechs during the war. Further, it explains their reconciliation with the establishment of the Protectorate and Czech collaboration, as well as for the expulsion of Sudeten Germans after the war.

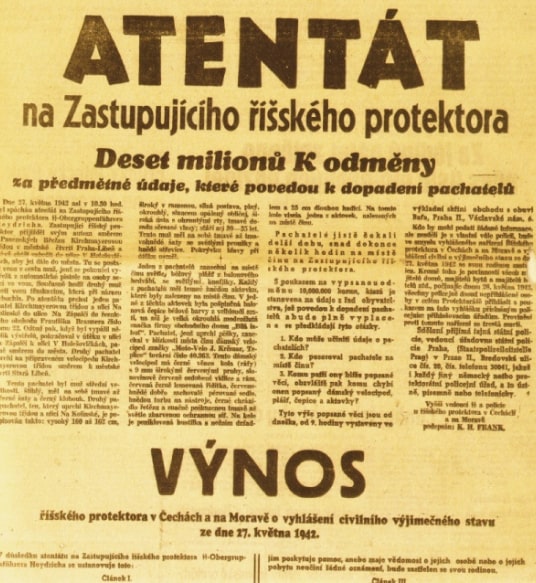

The assassination of Heydrich was a herioc achievement, but had serious consequences

Reinhard Heydrich, the author of the “final solution of the Jewish question” and Deputy Reich Protector, is the greatest Nazi demon for the Czechs, next only to Adolf Hitler. Heydrich was assassinated by Czech paratroopers in May 1942 — one of the most remarkable achievements of the European resistance (Válková, p. 77).

Nevertheless the action was followed by cruel repression. Nazi revenge was inflicted on everyone who had been even slightly suspected in connection with the attempt on Heydrich´s life. A village of 500 inhabitants — Lidice, near Kladno — was surrounded during the night of 10 June 1942 on the order of K. H. Frank 'Sudeten German official' on suspicion that they had helped the parachutists. Even though nothing incriminating was found there, all men older than 15 were executed, women were transported to concentration camps and children, excluding those designated for re-education, were poisoned by gas in Poland (Čurda, p. 82).

The perception of Stalin is a very peculiar one; he is not presented as one of the war heroes although he participated in the war on the side of the Allies. His character is the only one to undergo a fundamental development — first abjured for signing the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, then criticised because of his naivety about Hitler and his cunning when he stopped the Red Army before reaching Warsaw during the 1944 uprising. He is finally described, with mixed feelings, as “a member of the victorious antiHitler coalition” and as “the liberator of Central and Eastern Europe (Kuklíkovi). Source: Wikimedia

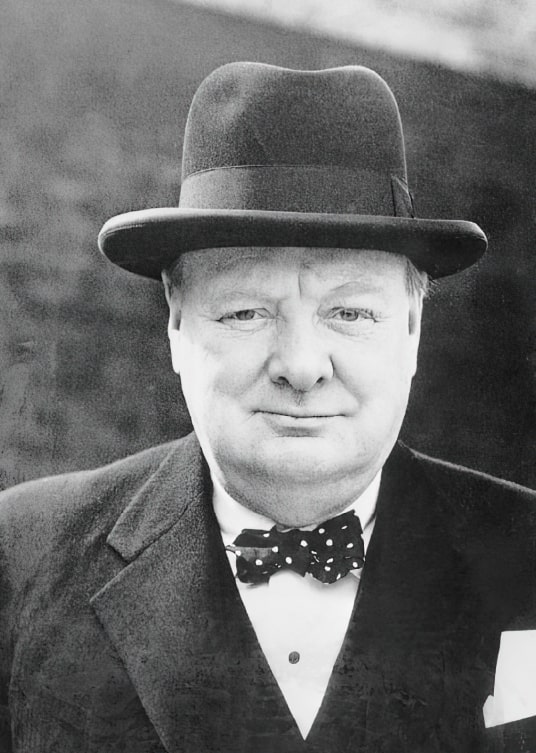

Winston Churchill, surprisingly a dominant figure of the Czech textbooks, is described as a proud and uncompromising politician who had the fate of the whole civilised Europe in his hands (Kuklíkovi, p. 66). Source: Wikimedia

In the Protectorate, the line between collaboration and resistance was razor thin

In the regime of fear and terror with which Nazis governed occupied lands, a certain level of cooperation and adjustment was essential for survival (Čurda, p. 79)

Alongside victims of the Nazi occupation there were three groups of people in the Protectorate. A minority of the population were informers and collaborators, motivated by cowardice, opportunism or conviction. However, most people simply tried to survive the occupation by means of passive resistance. Then there was the resistance movement; the army had been disarmed and geographic conditions made a guerrilla war out of the question. Consequently, the Czech people relied on their inventiveness and deftly conducted small-scale acts of sabotage that were difficult to punish (Kuklíkovi, p. 85).

The fate of the country was decided at the end of the war

During the war a division of Europe by the Iron Curtain was arranged, and since we fell into the sphere of Eastern influence we should be aware of how this happened (Válková, p. 33). At the beginning of the war, the opponents in the conflict were the democratic Allies and Hitler’s Germany. Especially France and Great Britain were initially initially described in an unflattering way as slow, wait-and-see democracies that prefer not to interfere because they lack the moral determination, leaving Central Europe at the aggressor’s mercy (Kvaček, p. 159).

For Nazi Germany and its allies, the war was clearly one of terror and extermination. These aims, therefore, had characterised the war against them as a fight in the interest of humanity and civilization, to rescue civic and democratic values. This cannot be changed even by the fact that it was the Soviet Union that became one of the main actors in the anti-Hitler coalition, a country suffering under Stalin’s dictatorship (Kuklík, p. 110).

This clearly shows the problematic perception of Stalin by the rather anti-communist textbooks and the negative attitude to his figure which originates in the post-war development of Central Europe.

Germany

The textbooks present the course of the war in brief facts. The most intense analysis is devoted to the subject of the Holocaust. Beyond that, the textbooks present, analyse and discuss several key topics.

The crucial question in all German textbooks

Nazi Germany is a symbol of the horror a modern industrial society is capable of creating. The systematic genocide against the European Jews and the purposeful initiation of WWII cost the lives of more than 50 million people. How was it possible? (Schöningh, p. 370)

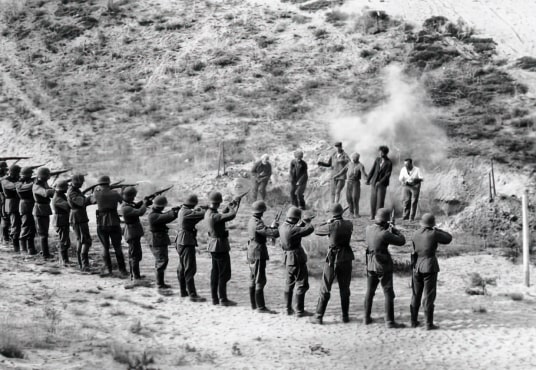

Ideological war of destruction against the Soviet Union — war crimes

The textbooks teaches through historical examples. Students are asked to analyze and evaluate a case of Nazi executions of Soviet citizens and the consequent impact on the Soviet people. The textbook presents materials including Nazi internal directives, military law and Hitler’s speeches which impart the ideological and racist origins behind the brutal acts against civilians. (Klett, p.250–251)

Postwar Germany:

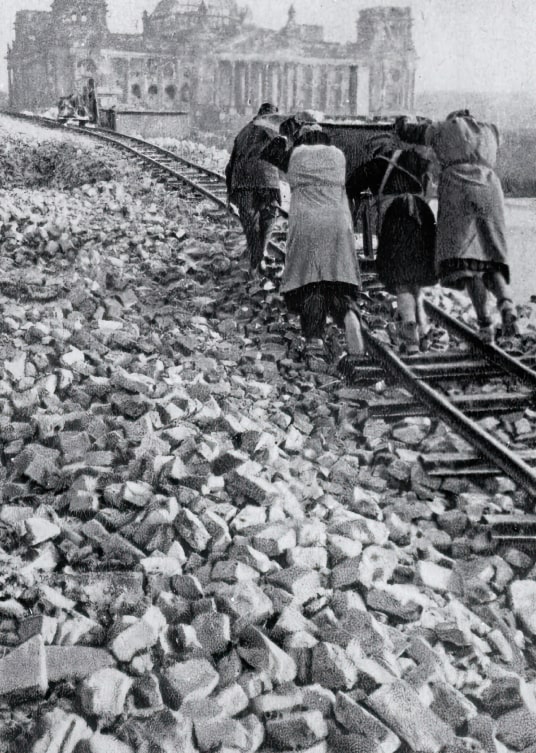

Collapse and new beginning 1945

Was the end of the war a structural break in German history — a “zero hour”? Was it only a short-term incursion in the long cycles of German history? Or, was 8 May the starting point of a long-standing period of reconstructing collapsed Germany? (Klett, p. 300)

The authors describe the governmental and moral collapse of Germany as well as the destruction and the misery caused by the war. The crucial themes are the decisions of the Allies at the Yalta and Potsdam Conferences and their implementation as well as the Nuremberg trials and the denazification. Allied plans for Germany — of the “four D’s” — are presented as an opportunity of a new beginning, but also as a way to divide Germany.

The Potsdam Conference (1945) proclaimed four guiding principles: denazification, demilitarization, democratization and decentralization; … However, between the Western Occupying Pow ers and the Soviet Union was no consensus about the interpretation and implementation of these basic principles (Klett, p. 410).

The textbooks mention the principal defendants and the num ber of convictions in the war crimes trial of Nuremberg and other subsequent trials. They are evaluated as an important contribution to informing the German society about the Nazi crimes and to democratization. The success of the denazification measures is critically reviewed.

The Wehrmacht in the war of destruction

After the war, the myth of a “clean” Wehrmacht (German army) was maintained. For war crimes mostly the Waffen-SS was blamed. This legend was destroyed by the “Wehrmacht Exhibition” in the years 1995 and 1999. To demonstrate that the Weh rmacht was not, in fact, “clean”, one textbook uses this example: A troop order developed on 6 June 1941 planned to imme diately liquidate commissars of the Red Army. That was against international law (Klett, p. 257).

Schöningh´s textbook describes that it was almost impossi ble for the regular soldiers to stay innocent in the process of relentless repression of the occupied territories. The extent of involvement of the Wehrmacht in the German occupation crimes, however, is still controversial (Schöningh, p. 398).

The Battle of Stalingrad: turning point of the war

The Allies finally prevailed with the defeat of the German Africa Corps in Egypt in November 1942 and the defeat of the sixth Army in Stalingrad in early February 1943 (Klett, p. 257).

In the textbooks the Battle of Stalingrad is perceived and emphasized as a turning point. Hitler’s command to Colonel General Paulus to continue with the fight (“Capitulation is out of the question”) is contrasted with the letter of a Wehrmacht soldier from the Stalingrad “pot” in January 1943. It is the fare well note to his father “The vast combat will not take place”: Do not seek explanations for the situation from us, but from you and the one who is to blame for it (Klett, p. 251).

Resistance in National Socialist Germany

The German resistance was a “resistance without people“. Its historical relevance lies especially in the courageous and outright commitment to freedom under the most dangerous conditions (Schöningh 1, p. 400).

| The authors describe the best known resistance groups: |

|---|

|

Communist and Socialists parties and the labour movement. The student resistance group “White Rose”: in leaflets they denounced the crimes of the Nazis. Military conspiracy: the failed attempt to assassinate Hitler on 20 July 1944, by Stauffenberg became a symbol of the German resistance (Schöningh 1, p. 403). |

The textbooks present and discuss the forms of resistance (Schöningh). They discuss the motivation for resistance and the problem of different resistance concepts (Klett)

Italy

Fascism in Italy – from collaboration to resistance.

At the outbreak of the war, Italy held a position of neutrality, but had secretly confirmed an alliance with Germany. Mussolini joined the war in June 1940. In July 1943, the Fascist regime collapsed and Mussolini was arrested. On 3 September 1943, the Italian government capitulated. In southern Italy the King and the antifascist parties collaborated with the Allies; in the north, fascist Repubblica di Salò became a satellite state of Germany. Towards the end of war Italy was a secondary front. On 25 April 1945, the National Liberation Committee (Comitato di Liberazione Nazionale, CLN) ordered a general revolt against the retreating enemy. Mussolini was captured and shot by partisans.

The strategy of a “Parallel war” failed

After the declaration of war Mussolini tried to develop an independent strategy (the so-called “Guerra parallela”), hoping to maintain some autonomy from Germany. The catastrophic results (Italy was unable to defeat the Greeks and had to abandon its Eastern part of Libya in 1940–41) showed Italy’s military weakness.

From 1941 Italy had to abandon the “parallel war”. In the spring of 1941, Italy collaborated with Germany in the attack on Yugoslavia. German armed forces became the backbone of the Axis army in northern Africa. Mussolini had to accept the help of the German army […]. The failure of the Italian initiatives in the Balkans facilitated the massive intervention of Germany as well (Giardina, p. 357).

The Italian army was sent to Russia in order to maintain the military prestige of the country but it suffered great casualties (1942–1943). Since this Russian “episode” played an important role in Italian collective memory, its absence in the narration of the textbooks is striking.

Italian war crimes are partly ignored

In April 1941, Italy occupied the middle-southern part of Slovenia, the coast of Dalmatia and Montenegro. Since 1941, Italian police and military forces had been combing the territory in Greece and Yugoslavia, executing civilians suspected of supporting partisans, carrying out aggressive campaigns and bombing whole villages that, as a result, were ultimately destroyed (Banti, p. 455). The Italian public is barely aware of these facts. However the Foibe — karst sinkholes where the Yugoslav communist partisans killed fascists, collaborationists and opponents of the new communist power at the end of the war — have received a lot of attention in recent years.

The significance of the Resistance movement is disputable

The impact of the Resistance is still controversial in Italian historiography. Some historians suggest that it should be called “civil war”, “patriotic war” or “class war” since Italian partisans were fighting against Italian fascists

The importance of the Resistance is stressed or diminished in accordance with the general political views on a given period and consequently with the tendency to underline or omit certain facts:

From a military point of view the impact of partisan actions was not crucial, but it doubtlessly was a nuisance for Nazi-Fascist troops. Moreover it constituted an important element of political legitimation for the CLN and for their government; it could be seen as the political projection of a popular rebellion, though it was clear that the majority of the population, in central and northern Italy, kept an attitude of fearful patience without openly siding with either the partisans or the Fascists (Banti, p. 464).

Racism was a part

of the Fascist ideology

In the Italian collective memory there has always been the myth of the “good Italian people”. That stands in striking contrast to the violence and massacres perpetrated by the Italian army in its colonies and to the aggressive behaviour of the Fascist government towards national and other minorities in the interwar period. But this is very rarely narrated in Italian textbooks, with some providing only minimal information.

Banti describes how the Italian popular propaganda imagery in Ethiopia was charged with sexual allusions: Evidence of this is shown in the song Faccetta nera (Little Black Face), a very famous song at that time, which invited the Ethiopian girls to wait for the arrival of the white “liberators” (p. 417).

In 1938 Italy joined Germany in creating their own anti-Jewish laws. On 13 July 1938 the Manifesto della razza was published, a document approved by the Ministry of Popular Culture and signed by Fascist scholars and professors of the Italian universities [...] It openly declared that Jews did not belong to the Italian race (Banti, p. 417).

The end of Fascism:

Italy split in two

The Anglo-American landing in Sicily marked the end of the Fascist regime. The news about the collapse of regime is met with enthusiasm: many men and women think that it is the prelude to the end of the war. […] Badoglio’s government, on the one hand, declares its commitment to Mussolini’s ideals, on the other it starts secret negotiations with the Anglo-Americans […]. Negotiations bring an armistice, signed on 3 September 1943, but announced five days later, on 8 September (Banti, p. 458).

Meanwhile German troops occupied the middle-northern part of Italy. The King and the government abandoned Rome and escaped to the South; the Italian army, left without command, disbanded.

Lithuania

Trapped between failing Western democracies and Communist expansion

Lithuanian school textbooks have varied in their focus of attention when describing the beginning of WWII. Numerous causes have been identified: the deterioration of international relations in the 1930s, aggressive policies resulting from rising fascist movements and the predatory goals of the Soviet Union. In some textbooks the blame for the war is not only attibuted to the “aggressors”, but also to the Western countries.

In the second half of the fourth decade the democratic states of the West adhered to the attitude which is known as the politics of “appeasement”. Its essence is an indulgence towards Germany led by Hitler in the hope that this would stop the expansion of communism in Europe and would become a counterbalance against the Soviet Union. To Western states, communism appeared a bigger evil than National Socialism (12th grade textbook by Navickas, Svarauskas, p. 79)

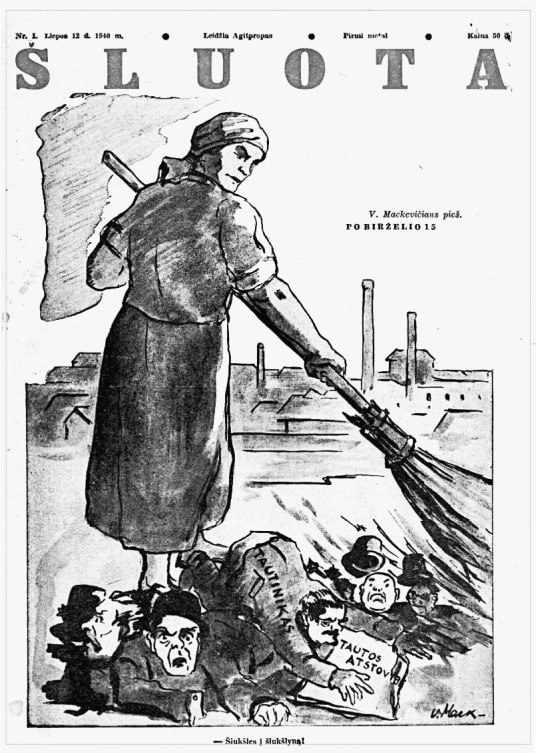

Lithuania’s reaction to the 1940 occupation — cowardice, helplessness or pragmatism?

President Smetona’s behaviour in the wake of the Soviet occupation is presented in a critical manner.

On 15 June President Smetona, having temporarily transferred the presidential powers to Prime Minister Merkys, escaped with his family to Germany without warning the people about the imminent danger. The same evening Soviet troops crossed the Lithuanian border and soon seized control over the country’s territory (10th grade textbook Tamošaitis, p. 154).

The Bakonis textbook presents a poem about the disappointment of the Lithuanian people, who felt betrayed by their former president and the Soviets: Although we all have promised to die for our Motherland, Our promises have been broken (p. 81).

On the same page the authors reflect that the previous compliant politics of the government can be acknowledged as reasonable under the conditions Lithuania lived in 1939/40. Students are asked to reflect on these two interpretations.

Collaboration — only half a story told

Lithuanians who cooperated with the Soviets are openly named collaborators. The textbooks present many illustrations and give the names of the ‘traitors’. The puppet government led by the journalist Justas Paleckis has become the state’s grave digger (10th grade textbook Kapleris et al., p. 109).

Collaboration with the Nazis is presented in a more reluctant, indirect or even apologetic way. Although the [Provisional Lithuanian] government had adopted some discriminating decrees, it still was not a German collaborationist. It first of all protected Lithuania’s interest (12th grade textbook Navickas, Svarauskas, p. 101).

During the Nazi occupation, the first General Advisor General Petras Kubiliūnas signed several decrees on the forced mobilisation of men for the German army. But his name is only mentioned in textbooks by Tamošaitis and Navickas.

Antisemitism — still a sensitive topic

The persecution of the Jewish population is often evasively described as ‘the Jewish tragedy’. Although the Lithuanian Activists’ Front (Lietuvos Akyvistų Frontas, LAF) had an explicit anti-Semitic programme, only Tamošaitis’s textbook identifies them as anti-Semitic. To quote one passage: Therefore the Lithuanian Jews have to bear responsibility for the attempts to diminish the Lithuanian people’s culture. […] until their fate is finally decided they should be immediately brought into camps for forced labour so that they don’t eat our bread but at least in some way participate in restoring what the fathers of the red spirit have destroyed using them as their tools (p. 187, excerpt from “To Clean the Lithuanian Nation from Fungus”, issued in Kaunas by the LAF on 5 July 1941). On the other hand the textbooks also emphasise that there were people who saved Jews.

The Second World War in a global dimension

In the Lithuanian textbooks, attention is given to Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact as well as the Soviet predatory goals. In this regard, Nazi Germany and the communist Soviet Union are identified as the countries that started WWII, whereas Japan and its aggressive politics are not even mentioned or referred to very briefly.

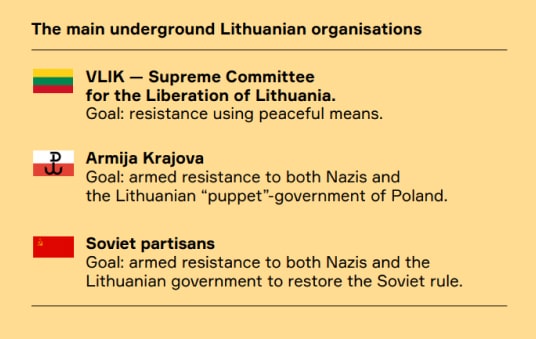

Different anti-Nazi resistance organisations

In the textbooks different weight is placed on the various anti-Nazi resistance organisations. Only Tamošaitis’s 12th grade textbook gives a detailed description of the Lithuanian Freedom Army. In contrast to this, all the textbooks give detailed description of the three main organisations.

Only in the Kapleris et al. textbook for the 10th grade, the Lithuanian-Polish conflict is depicted in more detail. Armed clashes of the Armija Krajowa with Lithuanian police battalions and the local squadron had begun, which mostly affected the peaceful local residents. Using the tactic of “divide and rule” the Nazis pitted nations against one another, instigating Lithuanians and Poles to fight (p. 114).

Poland

On 31 August, German Secret Police (SD) functionaries, dressed in Polish uniforms, captured a radio station and broadcast a speech urging an anti-German revolt […]. This event came to be known as the “Gliwice Provocation” and provided Hitler with a pretext for military action

The Polish September Campaign of 1939 — alone against two invaders

Germany attacked Poland on 1 September without prior declaration of war. Poland’s allies — Great Britain and France — eventually declared war on Germany on 3 September but did not immediately start military operations. On 17 September the Soviet Army crossed Poland’s eastern border, thus fulfilling the terms of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. Textbooks contain only indirect references to Poland’s desperate situation — the shock from the treachery and the feeling of isolation.

On 31 August, German Secret Police (SD) functionaries, dressed in Polish uniforms, captured a radio station and broadcast a speech urging an anti-German revolt [...]. This event came to be known as the “Gliwice Provocation” and provided Hitler with a pretext for military action (Roszak, Kłaczkow, p. 124).

The Soviet attack came as a surprise to Poland’s civil and military authorities.

The Commander-in-Chief issued a directive forbidding action against the Soviets unless they tried to disarm Polish units.

This decision, as well as the failure to officially recognise the USSR as an aggressor, proved to be a major political blunder. [...]

Gen. Władysław Langner, commanding the defence of Lvov against the German attack, surrendered to the Soviets, who guaranteed that prisoner-of-war rights would be respected, and he gave the city into “Slavonic” hands. [...] As soon as the city was occupied, a considerable number of policemen were murdered, and members of the military were sent to prisoner-of-war camps (Roszak, Kłaczkow, p. 127).

Similarities and differences between German and Soviet repressive tactics

Wide-ranging descriptions of repressive methods meted out against Polish citizens in territories occupied by Hitler and Stalin often appear under the joint title “Polish lands under two occupations.” There are frequent accounts of similar methods applied by both occupying forces. Differences in the scale of the repressions are also shown, together with those resulting from underlying ideologies and aims.

The Soviet occupants applied methods which had proved successful during the Revolution. They inflamed the age-old class and ethnic conflicts and made use of them to destroy the existing order. They encouraged looting and revenge, set up the poor against the rich, small-holders against landowners, and Ukrainians, Belorussians and Jews against the Polish people (Stola, p. 51)

The Germans introduced the death sentence for all attempts to help Jews, prisoners-of-war, escapees from camps and prisons, and members of the resistance movement. […] In territories occupied by the USSR, NKVD 'secret police' functionaries were as brutal as the Gestapo. In the autumn of 1939, a wave of arrests took place. The arrested Poles were sent to forced labour camps, detained in prisons or murdered (Roszak, Kłaczkow, p. 194)

The Polish Underground State — a unique resistance movement

Poland was conquered but, despite the declarations of the occupying forces, it did not cease to exist. By 30 September 1939 a government-in-exile was formed and work began on the creation of the Polish Armed Forces. The uniqueness of the Polish Underground State, however, laid in its military, political and civil administration structures.

Delegates, responsible to the Government Delegate for Poland, had their own underground resistance departments — equivalent to pre-war ministries. The Underground Army known as the Armia Krajowa (literally: ‘Home Army’, or ‘AK Underground Army’) − was the most numerous underground organisation in the world. By the end of the war it had more than 400000 sworn members.

The resistance movement set up by the Polish people and subject to the [Polish] government in London, was responsible for almost all aspects of public life. Apart from the battle against the occupying forces, sabotage operations, propaganda and intelligence programmes, there were also underground courts which could sentence traitors or German functionaries. Court orders were published in the underground press, and sentences were carried out by special units of the underground army. Entirely unique in Europe was the underground press which included not only journals of a political nature but also military journals, women’s magazines, and literary and satirical publications. In the territory of the ‘General Government’ there were over 2000 clandestine high schools, as well as institutions of higher education, teaching some 10 000 secret students during the war (Roszak, Kłaczkow, p. 190).

The Ukrainian-Polish

“war within a war”

Taking advantage of the defeat of the 2nd Polish Republic, the Ukrainians attempted to establish their own independent state — without national minorities. The greatest stumbling block in the realisation of the Ukrainian nationalist goals were the Poles, living in the territories of today’s western Ukraine.

In 1943, the UPA (Ukrainian Insurgent Army) began an ‘anti-Polish’ campaign, with an objective to cleanse the disputed areas of Volyn and Eastern Galicia of Poles. This was a genocidal operation: Ukrainian units attacked Polish villages, torching them and mercilessly murdering men, women and children. Approximately 100000 Poles lost their lives, a further 300000 fled the area. The UPA operation caused a civil war — a Polish-Ukrainian “war-within-a-war”: Revenge actions by armed Polish units also affected innocent Ukrainian civilians (Stola, p. 70).

Polish self-defence and revenge actions by the AK Underground Army contributed to the deaths of several thousand Ukrainians. Some of them, however, died at the hands of the UPA, mostly as a punishment for giving shelter to Polish neighbours (Roszak, Kłaczkow, p. 199).

Russia

Modern historians believe that the treaty of 23 August 1939 is easy to understand once we accept the assumption that Stalin wanted to avoid the Munich situation of 1938, when the USSR got excluded from world politics (Kiselyov, Popov, p. 126).

Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact: opinions diverge

The USSR’s policy in the spring-summer of 1939 remains a subject of intense debate among Russian history specialists, who still have not agreed upon a unified position on the issue (Zagladin, Kozlenko, p. 210–211)

The Kremlin dictator was exerting every effort to assure the Nazi leadership of that [that their eastern border was secure]. The German-Soviet Boundary and Friendship Treaty from 28 September 1939 as well as several trade agreements served the same purpose: they provided extra-large supplies of strategic raw materials and provisions to Germany, and facilitated naval operations under the guise of neutrality (Levandovsky, Schetinov, p. 182).

Life in occupied territories – confrontation between collaborators and partisans

The policy of economic plunder and merciless terror was maintained in the occupied territories; people that were deemed fit for work were forcefully sent to Germany (overall about 5 million people). The conditions of labour in factories, mines and railroads were back-breaking (Levandovsky, Schetinov, p. 207).

The scale of the collaboration and partisan-movement are still disputable.

Number of collaborators

| Kiselyov, Popov | 550000 |

| Izmozik, Rudnik | up to 1 mln |

| Danilov, Barsenkov | 1.5 mln |

Number of partizans

| Izmozik, Rudnik | 250000 |

| Levandovsky, Shetinov | 1 mln |

| Kiselyov, Popov | 1.3 mln |

Repressions and deportations under Stalin

They are sometimes criticised, sometimes omitted or carefully justified.

Numerous uprisings burst out in the Chechen-Ingushetian ASSR when German troops reached the North Caucasus. In Crimea more than 20 000 Crimean Tatars voluntarily joined anti-guerrilla squadrons to massacre those fighting against the Nazis. These actions became a pretext for mass deportations of the nations accused of aiding and supporting the enemy (Danilov, Barsenkov, p. 393).

The depraved practice of “punishing” small nations because a few individuals collaborated with the fascist occupation authorities is well known. Between 1943 and 1944 the Kalmyks, Karachays, the Chechen, the Ingushetians, Balkars, and Crimean Tatars were all deprived of their national identity and deported from their homes. Before that, in August 1941 the same happened to the Volga Germans (Levandovsky, Shetinov, p. 216).

The narration of the heroic home frontline has hardly changed since the Soviet era

An increased importance of the church’s role has been added to the textbooks, and there are more detailed accounts of deportations and repressive laws in Russian post-Soviet textbooks. Besides that, the narration sticks to the image of the unfaltering Soviet home front line.

The account of the Red Army liberating Eastern Europe almost always “stumbles” over the Warsaw uprising

Why was there no support for the rebelling population of the Polish capital? One answer:

From the very beginning the uprising was doomed, especially since its leaders did not ask the Soviet leadership to approve its timing and terms. The Red Army that had just driven the enemy out of Belarus needed a break. […] During the Cold War another version emerged: Allegedly, the Soviet command interrupted an offensive so that the supporters of the “London” government did not gain control in Warsaw. This point of view, however, is not backed by facts (Zagladin, Kozlenko, p. 251).

Different calculation methods applied to the Western matériel aid determine evaluation of the Allies’ contribution

The anti-Fascist coalition was unequally weighted throughout the entire Second World war. People of one of the members — the Soviet Union — bled on battlefields while other coalition members’ (Great Britain and especially the USA) efforts were limited to providing arms, supplies and provisions to the USSR up until the turning point in the course of the war. After the war was over, however, they tried to take advantage of the victory and even separate treaties with the enemy were not beneath them (Danilov, Barsenkov et al., p. 424).

The alliance between the USSR, Great Britain and the USA was an important factor during the war against the German-fascist aggressors. The lend-lease supplies of warfare material, cars, ammunition and provisions to the USSR turned out to be a significant contribution. It amounted to approximately 10% of all military Soviet aircrafts, 12% of tanks and 70% of cars (Zagladin, Kozlenko, p. 260).

Executions in Katyn

The majority of textbooks write about the execution of the Poles. One of them (Danilov, Barsenkov) explains it as a vengeance for the events of the Polish-Soviet War

Fate of Soviet war prisoners in USSR – is rarely discussed

For those who had once been surrounded, had escaped captivity or had just fallen behind their unit, there was no mercy. Most of the officers who were able to break out of an encirclement were condemned by court martials. A soldier who broke out of captivity or encirclement to find his unit could be condemned to death on suspicion of espionage, desertion etc. […] Former war prisoners and “encirclees” were put into special camps where they were forced to work in mines, pits, the metal industry, logging camps (Kiselyov, Popov, p. 155–156).

About Exhibition

Authors:

Algis Bitautas Lithuanian University of Educational Science,

Vilnius, Lithuania

Sylwia Bobryk University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth,

United Kingdom

Štefan Čok Independent historian,

Trieste, Italy

Giulia De Florio Memorial Italia,

Milan, Italy

Alicja Wancerz-Gluza KARTA Centre,

Warsaw, Poland

Friedrich Huneke Leibniz Universität,

Hannover, Germany

Nikita Lomakin Memorial International,

Moscow, Russia

Kristina Smolijaninovaitė CSF e.V., Berlin, Germany

Terezie Vávrová Antikomplex, z. s.,

Prague, Czech Republic

Gudrun Wolff Society of German-Russian Relationship,

Münster/Münsterland, Germany

Editors:

Robert Maier Georg-Eckert Institute,

Braunschweig, Germany

Julia Volmer-Naumann Geschichtsort Villa ten Hompel,

Münster, Germany

Translator:

Natalia Smirnova

Designer:

Mark Kalinin Taiga Creative Cluster,

St. Petersburg, Russia

Advisors:

Kamil Činátl Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes,

Czech Republic

Andrea Gullotta Historical Institute of the Warsaw University,

Warsaw, Poland

Jasper Kruse

Robert Latypov Youth Memorial,

Perm, Russia

Antonella Musumeci Garibaldi High School of Humanities,

Palermo, Italy

Maria Pavlikhina

Jan Krystian Scislowicz

Anna Sevortian CSF e.V.,

Berlin, Germany

Susanne Sternthal King’s College,

London, United Kingdom

Michaela Stoilová Gulag.cz,

Prague, Czech Republic

School Textbooks Reviewed

Czech Republic

Válková, Veronika Dějepis pro 9. ročník základní školy,

Praha: SPN, 2009

Čurda, Jan et al. Moderní dějiny pro střední školy. Světové a české dějiny 20. století a prvního desetiletí 21. století.

Brno: Didaktis, 2014.

Kuklíkovi, Jan & Jan. Dějiny 20. století. Učebnice pro střední školy.

Praha: SPL – Práce, 1995

Kvaček, Robert České dějiny II. Učebnice pro střední školy.

Praha: SPL, 2002.

Germany

Geschichte und Geschehen Qualifikationsphase Oberstufe. Stuttgart-Leipzig

Ernst Klett Verlag (quoted as Klett), 2011.

Zeiten und Menschen 1 und 2, Geschichte Kursstufe. Paderborn

Schöningh Verlag (quoted as Schöningh 1 and Schöningh 2), 2010.

Italy

Giardina, Andrea et al. Il mosaico e gli specchi. Percorsi di storia dal medioevo a oggi.

Roma-Bari: Laterza, 2006.

Banti, Mario Alberto. Il senso del tempo. Manuale di storia 1870-oggi.

Roma-Bari, 2008.

Poland

Roszak, Stanisław, Kłaczkow, Jarosław. Wiek XX. Podręcznik do historii dla szkół ponadgimnazjalnych.

Warszawa: Nowa Era, 2012.

Stola, Dariusz. Historia. Podręcznik klasa III. Szkoły ponadgimnazjalne. Zakres podstawowy.

Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Szkolne PWN, 2009.

Lithuania

Bakonis, Evaldas. Tėvynėje ir pasaulyje: istorijos vadovėlis 10 klasei

Šviesa, 2009.

Kapleris, Ignas et al. Laikas: istorijos vadovėlis 10 klasei.

Briedis, 2007.

Kapleris, Ignas et al. Laikas: istorijos vadovėlis 12 klasei.

Briedis, 2011.

Navickas, Virginijus. Svarauskas, Artūras. Istorija: vadovėlis 12. IV gimnazijos klasei

Kaunas: Ugda, 2015

Tamošaitis, Mindaugas. Istorijos vadovėlis 10 klasei. 1 dalis.

Baltos lankos, 2010.

Tamošaitis, Mindaugas. Istorijos vadovėlis 12 klasei. 1 dalis.

Baltos lankos, 2012.

Russia

Danilov, Alexandr, Barsenkov, Alexandr i dr. Istoriya Rossii. 1900–1945. 11 klass.

Moskva: Prosveshchenie, 2013.

Izmozik, Vladlen, Rudnik, Sergey. Istoriya Rossii. Bazoviy uroven.

Moskva: Ventana Graf, 2013.

Kiselyov, Aleksandr, Popov, Vasily. Istoriya Rossii. XX – nachalo XXI veka. Bazoviy uroven.

Moskva: Drofa, 2012.

Levandovsky, Andrey, Shetinov, Yury i. dr. Istoriya Rossii. XX – nachalo XXI veka. 11 klass. Bazoviy uroven.

Moskva: Prosveshchenie, 2013.

Plenkov, Oleg i dr. Istoriya. Vseobshaja istoriya. Bazoviy i uglublionniy uroven

Moskva: Ventana Graf, 2011.

Volobuyev, Oleg i dr. Vseobshchaya Istoriya. Bazoviy i uglublionniy uroven.

Moskva: Drofa, 2014.

Zagladin, Nikita, Kozlenko, Sergey i dr. Istoriya Rossii. XX – nachalo XXI veka.

Moskva: Russkoye slovo, 2007.

The contributors of this project made every effort to find all authors and copyright holders for illustrations, but unfortunately were unable do so for every image used in the textbooks. We fully respect the owners’ rights and would immediately credit them as soon as we identify them. We will be thankful for any information you can provide on this matter.

© 2015 by EU-Russia Civil Society Forum. © All rights reserved. This exhibition has been produced with the financial assistance of several donors. Its content is the sole responsibility of the EU-Russia Civil Society Forum and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of our donors or any other organisations. This is a non-profit project, and commercial use of this exhibition as a whole or any part of it is strictly forbidden.