This website uses different cookies. We use cookies to personalise content, provide social media features, and analyse traffic to our website. Some cookies are placed by third parties that appear on our pages. You can find more information and options to choose from in our Privacy Policy and Configurations for usage.

Lessons from the camps: how to learn about violations of basic human rights by visiting a former World War II concentration/extermination camp

Anna Skiendziel Complex of Technical and Secondary Schools No. 2, Katowice, Poland

15-20 years

45 mins preparation + 180-240 mins visit (travel time not included) + 45-90 mins reflection

Key question: How did genocide and crimes against humanity manifest themselves during World War II, and how can we prevent them in the future?

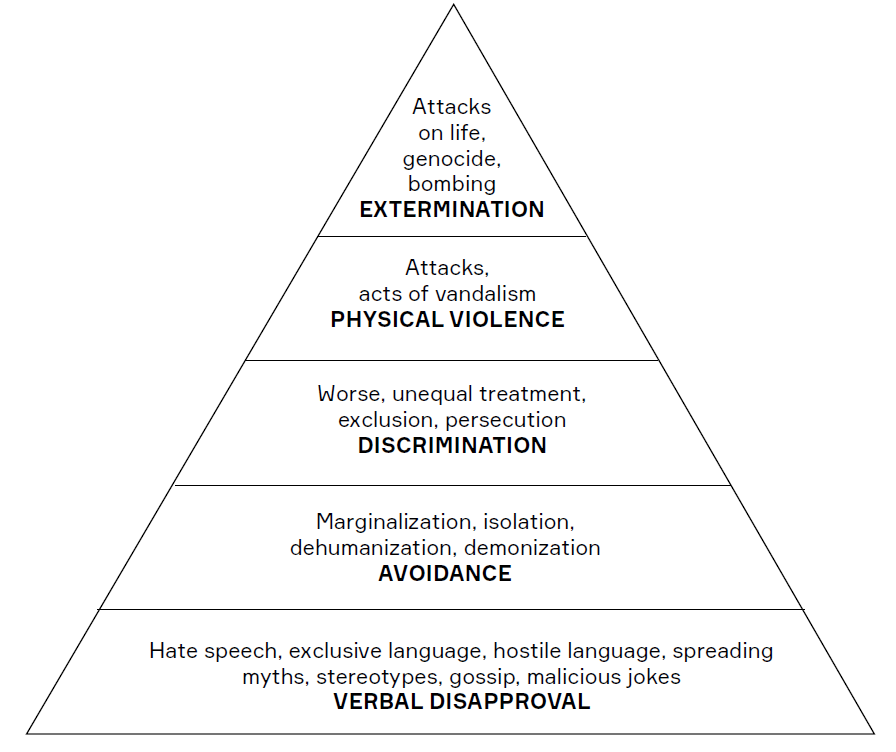

1 Gordon Allport was an American scientist associated with Harvard University. In his research, he noticed that crimes committed in the world, such as the extermination of Jews during World War II, were preceded by hate speech, exclusion, and discrimination against some social group or stratum, which he illustrated as a Pyramid of Hatred. It has 5 degrees: hate speech, avoidance, discrimination, physical violence, and extermination. Allport’s Scale measures the manifestation of prejudice in a society. It is explained in more detail below. See also Allport, G. (1954). The Nature of Prejudice, Cambridge: Addison-Wesley.

Learning outcomes

Students will:- Learn about the values of human rights and human dignity through discovering the history of the concentration camps and the conditions in which the prisoners lived.

- Learn about the stories of the survivors and develop empathy as well as learn about the feelings that may accompany a visit to a memorial site.

- Develop an attitude of respect for human rights and assume an attitude of responsibility in making decisions that may affect the fate of other people.

- Develop the ability to work in a group and draw conclusions from historical accounts and sources.

- Know and understand the process of violating democratic values, by being shown that anti-Semitism and xenophobia can lead to exclusion, discrimination, and genocide. They will understand the role of propaganda before and during the war.

- Reflect on democracy and the rule of law, identifying the circumstances where these values are threatened, and reflect on their own role and responsibilities, and their own potential to be influential.

Pedagogical Recommendations

The teachers should be familiar with the place that they will visit with the students. If the teachers have not been to that particular camp before, they should visit similar camps closer to their place of residence by way of preparation. Learning about the Holocaust should be adapted to the age and maturity of the students. Teachers know their pupils best, and they can talk with the guide before visiting.Preparation for the visit requires not only learning the history of the place, but also emotional preparation and behavioural tips. A visit to a memorial site is not a trip, such as to the mountains. It would be best if the trip were a separate school visit, not an element of an entertaining trip.

It is important to talk with students after the visit and reflect. The Holocaust should be a warning and an example of how violations of human rights, the principles of democracy, and xenophobia may lead to extermination and genocide.

Preparation Activities

In preparation for the learning activity and the trip, each student should watch one of the accounts of Holocaust survivors (see Appendix II for sources).Before watching, they should write down their answers to these questions:

- What do you expect to hear about?

- How do you expect to feel while watching?

- After watching, they should write down their reflections and feelings; the questions below can be used as a guide.

- What did you feel while reading? Did you experience any new emotions?

- What made the biggest impression on you? Why?

- What do you remember the most?

Stage 1: Introduction. 15 minutes

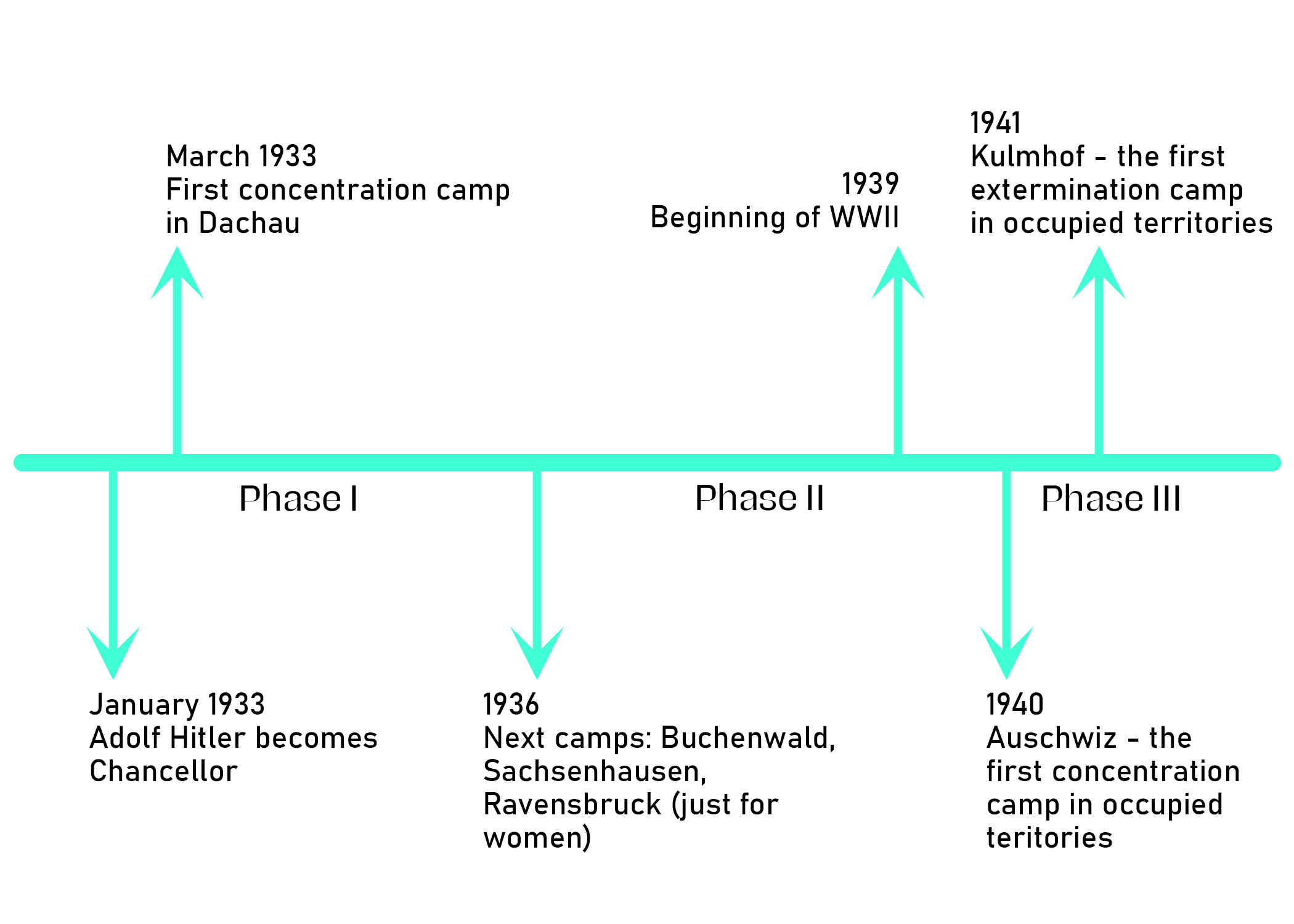

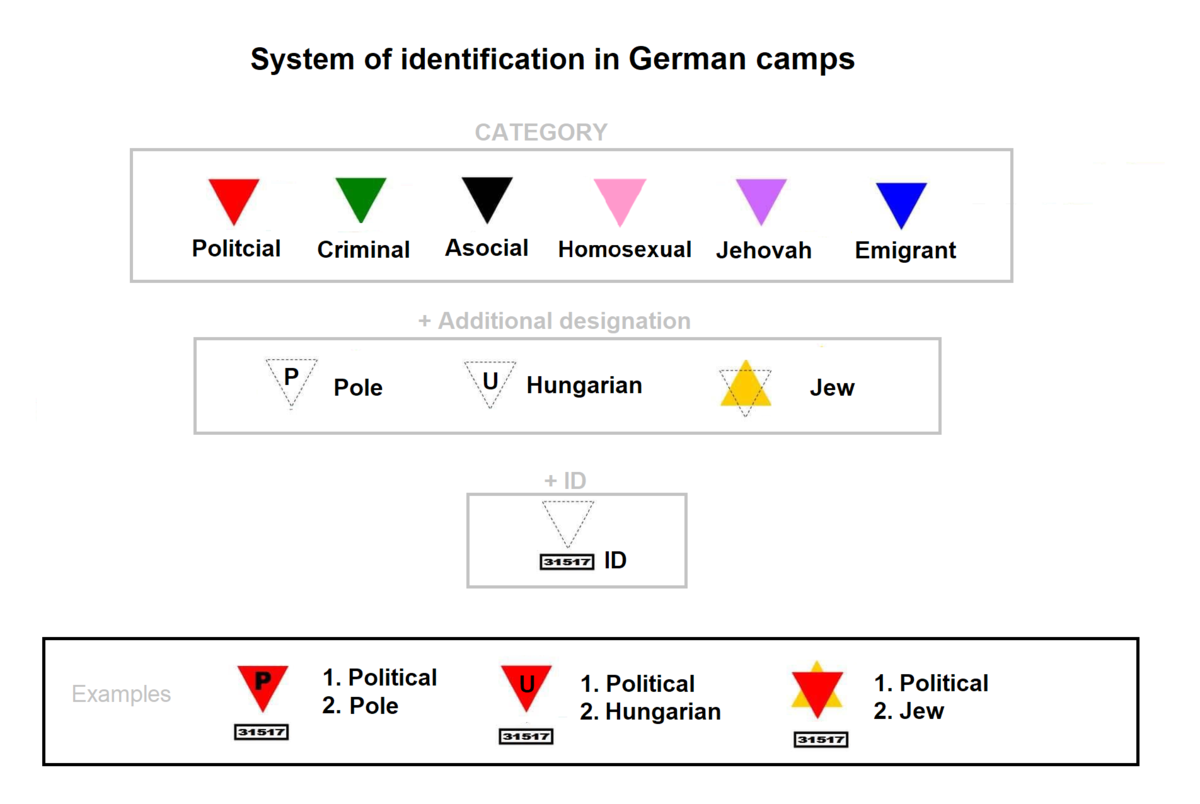

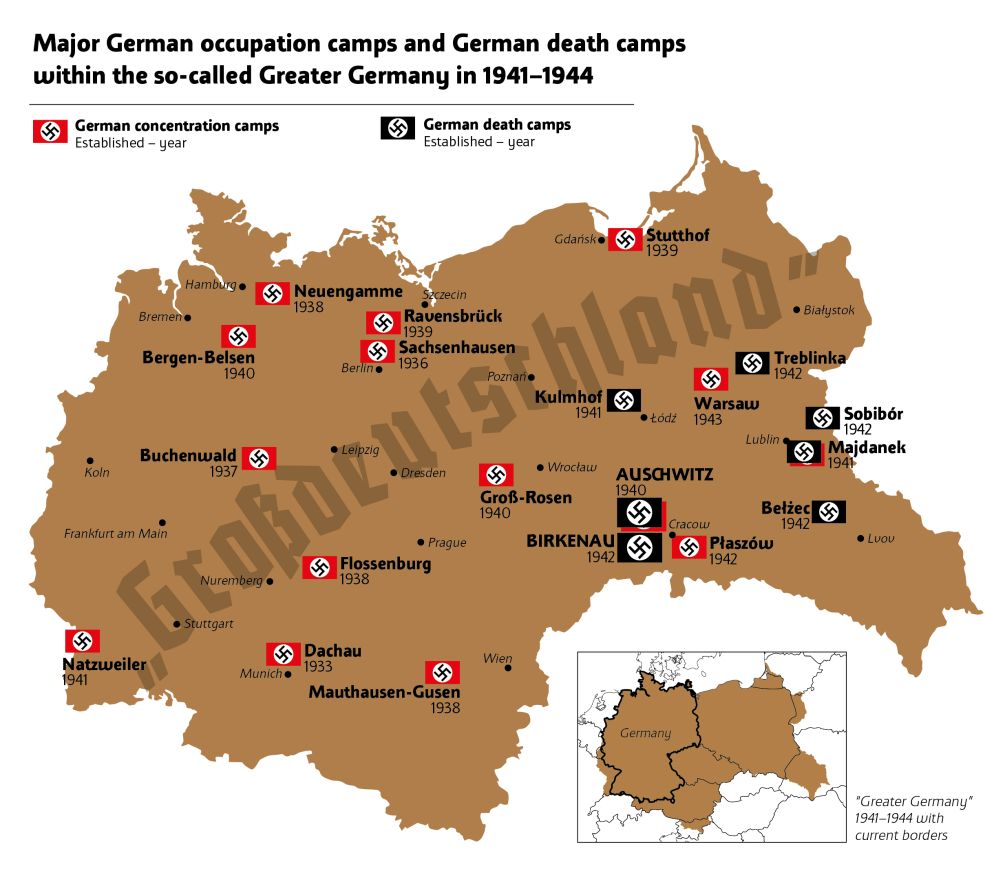

The teacher starts with an outline of the history of concentration/extermination camps in the Third Reich with the help of the following graphics. Showing the timeline is important for students to see that the whole machine didn’t start with the outbreak of the war or in 1940 in Auschwitz. The system of identification also shows that prisoners of the camps did not belong to one national or religious group, etc.

The teacher should show students maps and comment on them, showing the stages of creating the entire network of camps (16 camps and 900 subcamps).

This stage is very important and should not be avoided. It is very likely that the students will be in a place like this for the first time; it is necessary to talk about behaviour.

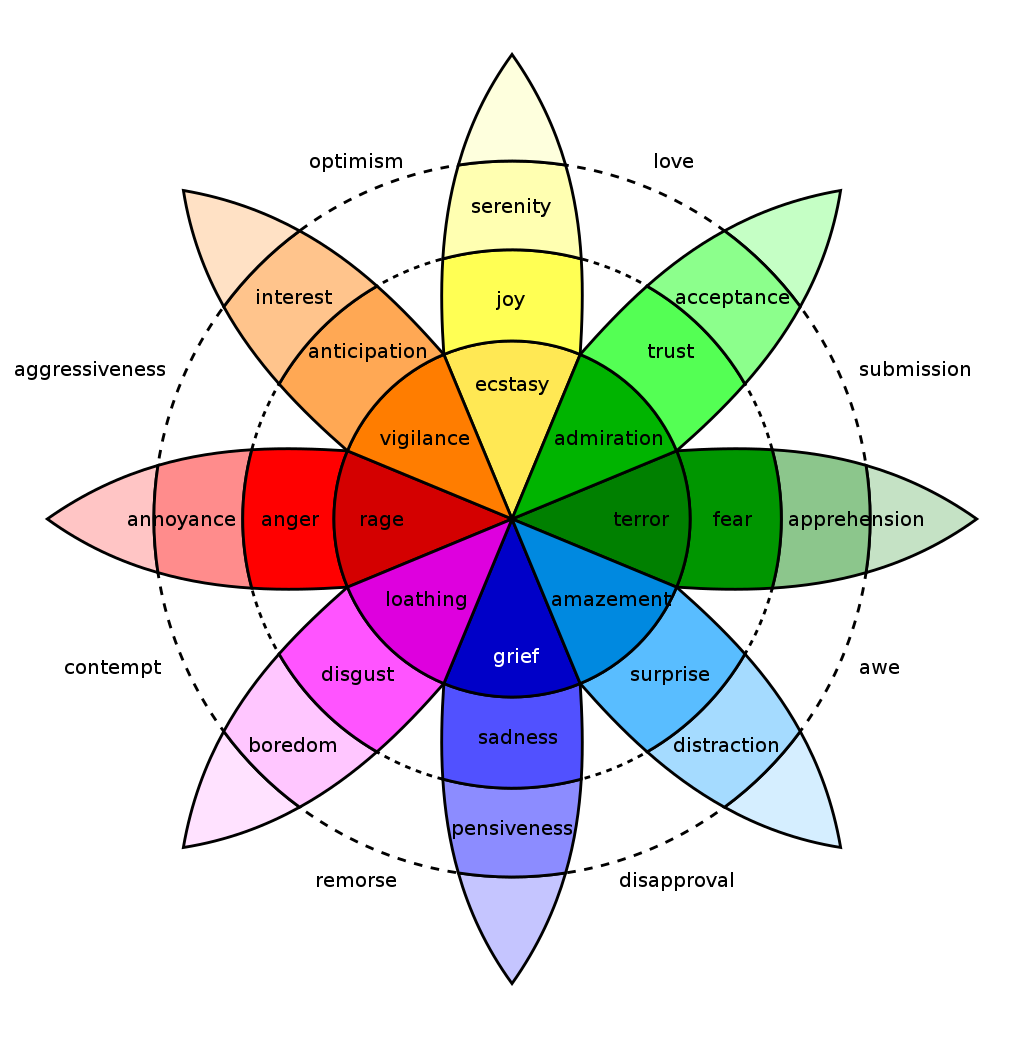

The teacher must talk with students about emotions. They have the right to emotions, crying, fear. They can leave an exhibition at any point, e.g., if they don’t want to see something. During the visit, students should know they can always approach the teacher, talk to them, comment on their feelings and observations.

The teacher should remind the students that it isn’t a pleasure trip but a visit to a memorial site, museum or cemetery.

Visit Activities

The teacher should not be overly active during the visit. Sometimes it is mandatory for a group to be accompanied by an official guide. They will tell the story of the place, show the exhibitions, or ask the students questions. Students should not be set specific tasks, and instead should concentrate as much as possible on this place of memory, on their emotions, on reflection, and not on the mechanical performance of tasks.At the end of the visit, the teacher asks for a 2-3-minute summary from the students and asks about their emotions. If students have questions about a place of remembrance or want to know something more, the teacher should give them the space and opportunity to ask about anything connected with the visit.

Reflection Activities

Stage 1: Reflection (obligatory). 45 minutesIt is necessary to organise an entire lesson after the visit and work through what the students saw and felt. In the beginning, the teacher leads an introductory conversation about the students’ emotions, and asks if they talked to someone about visiting the memorial site, e.g. a parent, sibling, or friend. Then the teacher returns to the questions introduced in the homework activity:

- What did you feel? Did you experience any new emotions?

- What made the biggest impression on you? Why?

- What do you remember the most?

- Students pair up and share their answers to the questions. Then – using the snowball method – the pairs form fours and exchange their reflections. Two more groups merge and four becomes eight. Finally, one person from the group presents what happened in their group, what the responses and feelings are.

- The second proposition is to use the Mentimeter app. It allows for anonymous individual sending of responses. It gives a sense of security, and students can submit any answer without pressure or fear. Finally, the teacher can display the answers and their comments on them.

Stage 2: Pyramid of Hatred (optional). 45 minutes

A visit to a memorial site is not only a study about this place and history, but it is supposed to have a universal message, showing the mechanisms that lead to extermination. Therefore, an important aspect after the visit is to show them how such a process can work. Using Gordon Allport’s Pyramid of Hatred, the teacher explains that what the students saw and learned about did not appear suddenly, but that it was a long process.

At the beginning of the lesson, the teacher may ask: Why has there been genocide and mass killing in Rwanda, Yugoslavia and Ukraine even after the experience of the Holocaust? How could this have happened?

Easier questions:

- Do you know any other examples where the Allport pyramid applies?

- Do you know any group that is facing negative comments, avoidance, or physical attacks?

- How can people react to and resist such mechanisms on their own?

- What can/should we do?

- Does one person's resistance make sense?

- Should knowledge about the persecution of Jews and their establishments be passed on and disseminated now?

- Do you know examples of statements/texts that deny the Holocaust?

- What were the attitudes of the world community that witnessed the extermination of Jews?

- Do these questions apply only to Jews? Have we been, or are we, witnessing persecution, tragedies of other nations, ethnic groups, or minorities?

Homework exercise

After the visit: Based on Marian Turski's speech (see below) and your own knowledge, please try to write, in about 200 words, an answer to the following: What conclusions can contemporary people draw from the experience of the Holocaust?Source: ‘Auschwitz, 75 years on: “Do not be indifferent”, says death camp survivor Marian Turski’, YouTube France 24 English, accessed 12 July 2022.

Assessment

Before the lesson, each student should watch one of the accounts of Holocaust survivors. After watching, they should write down their reflections and feelings. The teacher can check the comprehensiveness of the students’ homework.During the lesson and the visit, it is not the teacher’s role to assess. They might assess the students’ engagement during the lesson but bear in mind the potentially new and overwhelming environment.

The teacher can assess the short essay based on formal criteria, e.g. strength of the arguments. Content-wise, the teacher can judge the impact of their lesson and the effect that it had on the students.

Glossary

Here you can find definitions for the words in bold below.- Avoidance – dehumanising and isolating individuals and social groups.

- Discrimination – unequal treatment by both individuals and state institutions.

- Hate speech – dissemination of negative stereotypes combined with hostile, harmful language.

Appendix I – Lydia Tischler’s story

Read Lydia’s story and think about the following questions:- What did you feel while reading? Did you experience any new emotions?

- What made the biggest impression on you? Why?

- What do you remember the most?

What was your experience of Auschwitz?

Auschwitz was hell. Auschwitz was really hell. We were on the last but one transport to Auschwitz. In the last transport were all the prominent people from Terezin who went straight into the gas chamber. There were about 50 of us in a cattle truck with a bucket. That was it. We arrived in the middle of the night and in Auschwitz you could smell the fear. You really could smell the fear. And we had to go through selection. Mengele, of whom you may have heard, was standing there and he looked at you and then sent you to the left or to the right. The left was the side for living and the right was the side for gas. I knew that our mother… because she didn’t come to the left, she went to the right. But after the war I sort of hoped that maybe she was in some displaced persons’ camp. You know, that she wasn’t dead. That somehow, by a miracle, she escaped. We were herded into a huge hall and told to undress. And then somebody came and shaved all our hair. And then we were herded into another room where we sat on benches like in a theatre. And by then, people who had been there for some time told us, you know, you will go to the gas chamber, and so we sat there and, I must say, I sat there and didn’t know whether it would be water or gas. It was water. I remember when I came to Auschwitz, to a room where they took everything away from us, there was a wooden board with all the nationalities that were in the camp. And I think on top, I don’t think there were any English people, or any French. And the bottom two were the Gypsies and the Jews. And I remember, I have to remember this. For some reason it seemed to me important where they were putting us.

How did you cope from day to day?

I just took every day as it came. I worked in the market gardens. We were sometimes able to smuggle some of the fruit. For instance, cucumbers, if they were nicely bent, you could stick them into your bra and bring them into the camp. And, luckily, nobody was taking our clothes off to see what we had hidden. Potatoes you could put in your stockings. Tomatoes were not safe because they could squash and then that was it. Paradoxically, I got acquainted with cultural life while I was in Terezin. You know, all of the well-known actors, musicians, writers, professors were also in the camp. So, there was a rich cultural and intellectual life, as far as it was possible. I heard Verdi’s Requiem for the first time in my life in Terezin.

I would not have heard it if I had been at home at the age of 12 in Ostrava. Life, for people like me, wasn’t the worst. It was much worse for older people who felt the hunger and felt, you know, they had already had a life that they were deprived of.

What do you think about people who’ve denied the Holocaust over the years?

Usually, when a person denies something, it’s because he feels he has to deny it, because he’s a nasty man and he doesn’t want to feel nasty. So, he has to deny that anybody – you know, he perhaps would have liked to do it himself. This is how I understand, when people have to deny the horrors. In fact, when I came to England, I managed to find a school, and went to Brondesbury and Kilburn high school for girls. And when the girls heard where I came from, and they asked me questions, I thought, “How can they ask me these questions? They’ve seen the films”. But, when I studied psychology, I understood that, when things are so outside human experience, you really can’t believe it. We coped. I discovered late on when I studied psychology and psychoanalysis how useful defences are. You know, you could believe it and not believe it. You kind of told yourself, “No, they made a mistake. It can’t be true.” So people just went to Auschwitz and very few survived. I think one person escaped from Auschwitz, a Czech man who escaped and nobody believed him, what he told them.

As a survivor how do you want the Holocaust to be remembered?

The best way to remember it would be if people could learn from this experience so that it’s not repeated. And, in fact, it’s noteworthy that I’ve never felt that I needed to get revenge myself. I also haven’t felt like a victim. They didn’t succeed in making me a victim. I’m a survivor, which is something very different. We thought of them as inhuman but, I think, they never made me feel that I’m less than human. I could, you know, I had to put up with what they did to me. You know, when they told me to undress, if I said “I don’t understand” they’d have shot me or, I don’t know what they would have done. And although the Germans were able to take away all my belongings – almost everything, except my life, they left me alive. But, you know, whatever could be removed from my body, they removed from my body – they couldn’t remove my soul. My soul, they couldn’t remove my integrity, my inner self. That I managed to maintain. All of us have, you know, all of us have the capacity to be sadistic and horrible to other people. We manage to not do it, you know, but the potential for destructiveness is in all of us. I actually believe that people are born – well, they’re born neither good nor bad and that the badness is a result of the way someone is treated as a child. I believe that if you’re treated well as a child, you can’t become a Hitler.

Source: ‘Holocaust survivor interview, 2017’, YouTube Channel 4 News, accessed 12 July 2022.

Appendix II – Recommended reading and further research for teachers

We recommend the following sources to prepare for a trip to a concentration or extermination camp:- (PL) ‘Zalecenia i wskazówki dotyczące edukacji na temat II wojny światowej i Zagłady’ [Recommendations and tips for education about World War II and the Holocaust], POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews, accessed 24 January 2023.

- (EN) Białecka, A., Oleksy, K., Regard, F. & Trojański, P. (eds.) (2010). European pack for visiting Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum: Guidelines for teachers and educators. Strasbourg: Council of Europe, accessed 24 January 2023.

- (EN) ‘Institute of National Remembrance: Truth about Camps’ – information about concentration/extermination camps in occupied Poland, accessed 24 January 2023.

- (EN) ‘Holocaust Encyclopedia’ – articles, digitised collections, critical thinking and discussion questions, lesson plans, oral histories, videos, accessed 24 January 2023.

- (EN) ‘Centropa’ – archive with biographies, interviews, photos and documents from Holocaust victims and survivors, accessed 24 January 2023.

- USC Shoah Foundation YouTube channel, accessed 24 January 2023.

- ‘Torchlighters 2020’, Yad Vashem YouTube channel, accessed 24 January 2023.

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum YouTube channel, accessed 24 January 2023.

Download guide

Other Lesson Materials

The beginning and end of World War II

Children in World War II

Remembrance and memorialisation of World War II in different countries

Young people and forced labour during World War II

Border changes resulting from World War II

Consequences of World War II