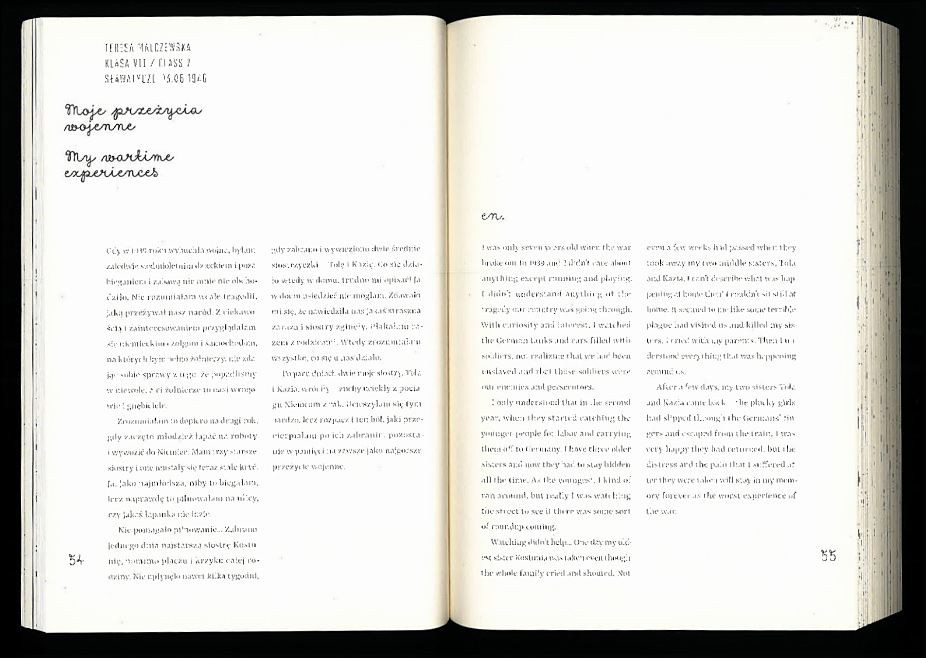

From the book: “My wartime experiences: Children’s writings from 1946”

1 September 1939

Beatrice Paetzold Brücke/Most-Stiftung, Dresden, Germany

16-19 years

90 minutes

General Information

General information on the beginning of World War II on 1 September 1939

September was completely dominated by the war started by Germany: at 4.45 a.m. on 1 September, the German warship “Schleswig-Holstein” opened fire on the Westerplatte1 in Gdansk, and at 5.45 a.m., after a faked German “attack” on the Gliwice station2 , the war of which many were afraid had begun. At 10 a.m. Adolf Hitler, in a speech in the Reichstag3 broadcast throughout the German Reich4 , justified the attack on Poland, which was carried out without a declaration of war. In his speech, he avoided the word “war”. The German press were likewise told to avoid the use of the word.

On the morning of 3 September, after two days’ hesitation, Great Britain, followed shortly afterwards by France, declared war on the German Empire, whereupon the Germans launched a naval war against the British Empire.

After Soviet troops had invaded eastern Poland on 17 September - as agreed in the supplementary agreement to the Non-Aggression Pact5 in August - German and Soviet troops met for the first time the following day near Brest6 . On that occasion both sides issued a joint statement to the effect that they would not pursue conflicting interests in Poland. On 22 September German troops withdrew to the agreed line.

The day before, Reinhard Heydrich7 , as head of the SS8 Security Police and Security Service, had outlined the policy to be pursued by the German occupying forces in Poland: Liquidation of the intelligentsia, ghettoization of the Jews, and the resettlement of the Polish population to a residual Poland known as the “Generalgouvernement”9 , the capital of which would be Krakow.

According to the Wehrmacht High Command10, the campaign in Poland was over by 23 September. However, this did not prevent the German Air Force from massively bombing Warsaw two days later - an unnecessary attack that claimed more than 10,000 lives. On 27 September, the city capitulated, and 140,000 Polish soldiers fell into German captivity.

The beginning of the war naturally brought about serious changes for daily life on the territory of the Reich, which was now considered the “home front”11. As early as 1 September, a complete black-out was ordered, and the tapping of “enemy transmitters”. Spreading news heard on “enemy transmitters” was severely punished. Changing jobs without official permission was now completely impossible. On 3 September, the decree on “Principles of Internal State Security during the War” was published, in which Reinhard Heydrich, as head of the SS Security Police and Security Service, explicitly threatened to intervene ruthlessly against anyone who publicly doubted the German victory.

Further, far-reaching measures followed: On September 4, by decree of the Council of Ministers for the Defence of the Reich, the size of the Reich Labour Service12 (for young women between the ages of 17 and 25) was increased to 100,000. On the same day, the Council also issued a “war economy ordinance”, which included a rise in income tax as well as surcharges on tobacco, beer and other alcoholic beverages. At the same time “war wages” were introduced, which also meant that bonuses for Sunday, holiday and night work were to be abolished. A Council of Ministers decree against “pests of the people”, operative from 5 September, prescribed the death sentence for looting in cleared areas and crimes committed during an air-raid alert.

By an order of 6 September the Reich Minister of Transport prohibited the use of private motor vehicles from 20 September. Exemptions were possible only if their use was in the public interest. On 25 September, an Ordinance made on 7 September and concerning foodstuffs and luxury foods came into effect in the Reich. From that date, bread, milk, meat, fat, jam and sugar - some of which had been freely available until then - were only 3 Lesson material The beginning and end of World War II Lesson 90 min sold against food ration cards. The same applied to soap and washing powder. Whole milk was only available for children, pregnant women and those carrying out the heaviest forms of work. These groups of people were issued with special cards.

There were, however, some small reliefs. For example, the ban on public dances, imposed on 4 September, was lifted again at the end of the month. And on 9 September Hermann Göring13 tried to boost morale when, in a speech to workers at the Rheinmetall-Borsig- Werke14 in Berlin-Tegel, broadcast by all German broadcasters, he declared that the German Reich was the best-equipped state on earth.

For one part of the population, the beginning of the war presented an extremely threatening and largely hopeless scenario: A police regulation imposed a curfew on Jews in the German Reich right at the beginning of the war, and from 20 September they were forbidden to possess radio receivers. Above all, however, the war closed off the last possibilities for emigration. ...

By order of [...] the Minister for Education [...], the “Primaner”15 drafted into the Wehrmacht were given the so-called “Reifevermerk”16 on 8 September. Secondary school pupils were also granted this qualification if they had been active in war aid service17 until April 1940.

866 words

Source: September 1939,

https://jugend1918-1945.de/portal/Jugend/info.aspx?bereich=projekt&root=10382&id=22583&redir=

Last visited: 11/01/2021

Glossary of terms

1 Westerplatte is a peninsula in the Free City of Danzig where a fortified Polish ammunition depot was located from 1924 to 1939. The Free City of Danzig (today Gdańsk, Poland) was a city in the northwest of Poland, in the province of Pomerania. From 1920 to 1939 it was under the protection of the League of Nations and granted the status of a partly sovereign, independent Free State with Polish port rights.

2 The Gliwice Station was a radio station in Gliwice-Szobiszowice (formerly Gleiwitz- Petersdorf) in the Polish province of Silesia.

3 Under the Weimar Reich Constitution, the Reichstag was the parliament from 1919 to 1933 and thus one of the supreme organs of the German Reich. The Reichstag met in the Berlin Reichstag building.

4 German Reich was the name of the German nation state between 1871 and 1945. After the “Anschluss” of Austria (annexation of Austria into Nazi Germany) in March 1938, the term “Großdeutsches Reich” (Greater Germany) came into official use, and was used in propaganda.

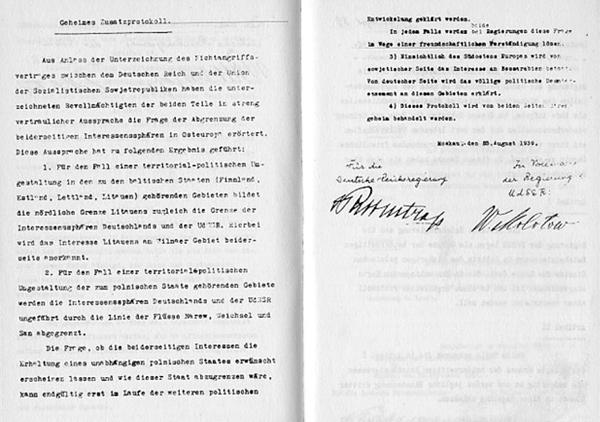

5 In the secret supplementary protocol to the Hitler-Stalin Pact of August 1939, the Soviet Union and the German Reich agreed on the allocation of countries between themselves. Finland, Estonia, Latvia and Bessarabia were annexed into the Soviet Union, and Lithuania and South-East Europe into the German Reich.

6 Brest today is a city in Belarus, and used to be the main border crossing with Poland.

7 Reinhard Heydrich (1904 - 1942) was, among other things, deputy Reichsprotektor in Bohemia and Moravia (the parts of Czechoslovakia under German rule from 1939-1945). In 1941 he was put in charge of the “Final Solution of the Jewish Question”, and after that time he was one of the main organisers of the Holocaust.

8 The Schutzstaffel (SS) was a National Socialist organisation during the Weimar Republic (1918 – 1933) and the period of National Socialism (1933 – 1945), serving as an instrument of domination and oppression for the NSDAP (Nazi party from 1920 - 1945) and Adolf Hitler. From 1934 onwards, its responsibilities included the administration of concentration camps and, from 1941 onwards, of extermination camps. The SS was primarily involved in the planning and execution of the Holocaust and other genocides.

9 Just over one month after the German Wehrmacht invaded Poland on 1 September 1939, the country was redivided. The western parts were annexed by the German Reich, while eastern Poland fell to the Soviet Union. Central Poland, including Krakow and Warsaw, was called the “Generalgouvernement”. In the long term, the Nazi regime planned to remove the majority of the Polish population from the Generalgouvernement altogether, and to replace them with so-called “ethnic German farmers”, thus expanding German “living space”.

10 The Wehrmacht was the name given to the combined German armed forces in Nazi Germany. It was divided into the army, the navy and the air force. Together with the Army High Command, the Navy High Command and the Air Force High Command, the Wehrmacht High Command was one of the most senior staff organisations in the Wehrmacht.

11 The “home front” was a construct of Nazi propaganda to document and strengthen the alleged bond between the soldiers fighting at the front and those left behind at home. As the war progressed, the term was adopted for the entire work deployment at home.

12 Male and female youths aged between 18 and 25 were obliged to serve in the Reichsarbeitsdienst (Reich Labour Service). The task of the Reichsarbeitsdienst was to “educate German youth in the spirit of National Socialism as a national community” and to “carry out community service work”, such as the development of moorland or work on motorway construction. Towards the end of the war, the focus turned almost exclusively to military training.

13 Hermann Göring (1893 - 1946) was a leading German National Socialist politician. From May 1935 he was commander-in-chief of the Air Force. From 1936/1937, he took over the leadership of the German economy and the Reich Ministry of Economics.

14 Rheinmetall-Borsig-Werke is a German mechanical engineering company based in Berlin, specializing primarily in the construction of locomotives.

15 Primaner were pupils in secondary school, mostly aged 16-19.

16 Pupils called up for the Reichsarbeitsdienst (Reich Labour Service) or the Wehrmacht received a “Reifevermerk” (Maturity note), which included permission for a university presemester (to be taken once their service was completed) designed to help them catch up on the knowledge required for university studies.

17 As early as at the beginning of the Second World War, the Kriegshilfsdienst (war assistance service) was introduced as a temporary measure for pupils in secondary schools, e.g. for the distribution of food ration cards. Officially, this kind of military service was to be carried out in social institutions, in hospitals, and with needy families, or in government service and at offices of the Wehrmacht. In fact, in the winter of 1942/43, the majority of young women worked in transport companies and the arms industry.

Diaries / Memoirs (Germany)

The beginning of war on 1 September 1939

Memoirs written by Werner Mork (*1921) from Bremen, a town in the north of Germany, written in July 2004

“On September 1st, 1939, I went happily into the kitchen to my mother. I had slept soundly and felt fresh and well. But I sensed that something was making my mother nervous. On her way to the bakery, she had heard that an extraordinary meeting was scheduled at the Reichstag [Assembly of the Empire], at which the Führer [political title associated with the Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler] would give a speech on the issue of Poland. All Germans were ordered to tune in. It was a duty for all Volksgenossen1 [citizens of German blood], even at workplaces. My mother was worried and said it could lead to war. My father and I disagreed with her.

In the end, I found myself caught up in the general agitation, though I still thought that a potential war was just a nasty rumour. I heard on my way to the station that it was more than a rumour now; the war had become reality. Some people were even saying that the war against Poland had already begun the previous night. They’d somehow got that idea from somewhere. If that were to be true, the Führer would address it in his scheduled speech. Everybody was waiting eagerly for the speech to start.

At work, I had to arrange everything to make sure that we all listened to the broadcast, as ordered. At 10 o’clock, the Großdeutscher Rundfunk [the unified broadcasting company of the National Socialist German Reich from January 1st, 1939 to 1945] aired the Führer’s speech from the Reichstag on all Reich programs broadcasting on the short wave.

The Führer’s broadcast was heard throughout Germany and in many other countries. He declared that the boundless insolence of the Poles towards the German Reich, the city of Danzig [note: today Gdansk, a city in Poland; from 1920 to 1939 a free city with a predominantly German-speaking population] and the Volksdeutschen2 [ethnic Germans abroad] in Poland was to end.

‘Since 5 a.m. we have been returning fire, and from now on bombs will be met by bombs, shells by shells.’3 The German Reich was said to be at war with Poland now; the Polish people had not wanted it to be any other way; they had rejected the outstretched, peaceful German hands. In the same address, the Führer also announced the annexation of the City of Danzig to the German Reich. And he explained, too, that the Führer would from now on once again wear the field-grey military tunic, the Robe of Honour of the Nation. He would not put aside that tunic until the war had ended in victory for Germany.

Thunderous applause, given by the representatives of the Reichstag to their Führer, could be heard in Germany and other countries. Then the national anthems were sung, and we listened to them at work, standing. Nobody sang along.

The meeting was over. Among the Gefolgschaftsmitgliedern4 [members of the youth organisation Hitlerjugend HJ], there was a rather solemn silence. The head of the department noticed it, and said: ‘Let’s get back to work, and do our best.’

I found this behaviour and the silence somewhat surprising. Was it not the head’s duty to shout at least a ‘Sieg Heil’ [a gesture that was used as a greeting in Nazi Germany] to the Führer? I suppose I must have been quite naïve.

And shouldn’t we have sung along with the German national anthem at this solemn moment? Shouldn’t we have expressed ourselves as joyfully as people had done back in August 1914 [the outbreak of the First World War]? Shouldn’t we have shown that our little company fully supported our Führer in this great hour and in the difficult time to come?

I couldn’t really understand it, and I decided to do my own thing. I went to the top of the building, looking for two flagpoles with the national flags. I thrust them out of the top windows, and the two flags—one black, white and red and the other with a swastika—waved happily in the morning breeze of September 1st, 1939 above Katharinenstraße. I was convinced that the flags had to be raised that day; I saw it as my duty.

Nobody took notice of my (spontaneous) audacity, until a call came from the police station to the company. They were furious, and asked who had raised the flags in the building. I think they even said ‘idiot’. No permission had been given for the flags to be raised, and the flags had to be taken inside again immediately. So, everybody knew now about my spontaneous act. I was given a good ticking-off and had to pull the flags back inside. I got a helping hand from the warehouse, because I could not manage it on my own. So ended what was probably the one and only flag-raising to mark the start of the war, not just in Bremen but in the entire Greater German Reich. But I was nevertheless of the opinion that my actions were perfectly justified. [...]”

846 words

Source: Mork, Werner: Kriegsbeginn am 1. September 1939, in:

LeMO-Zeitzeugen, Lebendiges Museum Online, Stiftung Haus der Geschichte der Bundesrepublik Deutschland,

http://www.hdg.de/lemo/zeitzeugen/werner-mork-1945-den-krieg-ueberlebt.html

last visited: 11/01/2021

Glossary of terms

1 Volksgenosse (translated literally as ”people’s comrade”)

The term Volksgenosse (a fellow member of a community or a compatriot) became common parlance within the Nazi Party, as a way to distinguish ethnic Germans from other groups, such as Jews and Gypsies. The term Volksgenosse was formalised in the Nazi Party’s Program in 1920 as a racial ideological term: “Only a Volksgenosse can be a citizen. Volksgenossen are only those of German blood, regardless of denomination. No Jew can therefore be a Volksgenosse”. Adolf Hitler extended the racial connections in his autobiographical manifesto “Mein Kampf” (My fight) with classifying population groups as “anti-social” or “disabled”.

2 “Volksdeutsche” (translated literally as ”People’s Germans“ or ethnic Germans abroad)

In Nazi Germany Volksdeutsche were “people whose language and culture had German origins but who did not hold German citizenship”. The Volksdeutsche shed their identity as Auslandsdeutsche (Germans abroad) and morphed into the Volksdeutsche in a process of self-radicalisation. This process gave the Nazi regime the nucleus around which the new Volksgemeinschaft (People’s community) was established beyond German borders.

3 ‘Since 5 a.m. we have been returning fire, and from now on bombs will be met by bombs, shells by shells.’

This should read: “... Since 5 a.m., we have been returning fire, and from now on bombs will be met by bombs! Who fights with poison gas, will be fought with poison gas. [...]”. Hitler made this promise himself in his speech. The shots were actually fired at 4:45.

4 Gefolgschaftsmitglieder (Followers)

The Hitler Youth (HJ) was a youth organization of the National Socialist party, the NSDAP. Its main task was to educate young people in the spirit of the Nazi ideology and thus to permanently secure the rule of National Socialism. The HJ was strictly hierarchical and undemocratic. One unit of it was the Gefolgschaft (about 250 boys), each of which was subordinate to a Gefolgschaft leader.

Children’s Memories from Poland

Janusz Tarnowski, 6th grade, written on 17 June 1946

When the war began, German planes came over and bombed Warsaw. The bombardment lasted for somewhere between three and five hours. During that time I was down in the basement with my entire family, except for my father, who had gone to fight.

We stayed in the basement for whole nights or days. When we ran out of food, I went with my older friends to get food from demolished shops.

While we were in Powiśle, we were surprised by a German air raid. We hid in the rubble of a ruined townhouse. After a short discussion, we decided to run to the other side of the Kierbedź Bridge. We were more than halfway across when planes came and began to drop bombs on the bridge. But the bombs missed the target and fell into the Vistula, making water spurt up as if from erupting volcanoes. When we crossed the bridge, shells fired by the German artillery were exploding in the streets.

We ran to the other side of Jagiellońska Street. A shell landed at the corner of the street. One of my friends got wounded. We dragged him to a nearby shelter, where the Red Cross took care of him. We wasted no time, and ran on. We soon reached our house and found our mothers in tears.

On the following night a few families proposed that we leave Warsaw. We were caught by a raid on the way. Everybody fled where they could; my mother, brothers and I escaped to a nearby house. When we entered it, a bomb fell some 10 meters from the house. My mum was showered with rubble, but my brother and I managed to run out of the building.

The next day, when my mum felt better, we set off for the countryside. A few days later we saw Germans going through the village. When we came back to our flat in Warsaw, we found father there, wearing his civilian clothes.

Jadwiga Zyn, 6th grade, written on 14 June 1946

When word spread about the war, many people left town. Shelters were built throughout Warsaw. On 1 September 1939 I heard the first shots, and German planes appeared in the sky and began to attack Warsaw. People fled to the trenches. My mum, grandma and I hid in the shelter. The raids were very frequent and lasted for a few days. On the seventh day the district where I lived was demolished.

We left Warsaw that same night. We walked for a long time and finally we reached Stoczek. The town of Stoczek had been burned to ashes. We lived there until September, and then returned to Warsaw.

I saw great devastation on the way. Warsaw had been turned into a huge cemetery. The house where we had lived was half demolished. After we rebuilt it we lived there until February, and then we went to our family in Liszna village on the Bug River.

In 1944 when the front was approaching, we dug a shelter and stayed there, with bullets flying over our heads. The Germans and the Soviets fought on the other side of the Bug. I could clearly hear the Soviet soldiers shouting, “poddaysa”(“surrender”). The Soviet troops entered Leszno shortly after. They had cars, tanks and different sorts of cannon.

I am a child of Warsaw, and I’m terribly sorry that the enemy devastated it so much. Every day I send up prayers to the Mother of God to let us rebuild it and for me to be able to return there.

Teresa Maczewska, 7th grade, written on 13 June 1946

I was seven years old when the war broke out in 1939 and I didn’t care about anything except running and playing. I didn’t understand anything of the tragedy our country was going through. With curiosity and interest, I watched the German tanks and cars filled with soldiers, not realizing that we had been enslaved and that those soldiers were our enemies and persecutors.

I only understood that in the second year, when they started taking the younger people and carrying them off to Germany to work. I had three older sisters and now they had to stay hidden all the time. As the youngest, I kind of ran around, but really I was watching the street to see if there was some sort of roundup coming.

Watching didn’t help. One day my oldest sister Kostunia, was taken even though the whole family cried and shouted. Almost straight after that, they took away my two middle sisters, Tola and Kazia. I can’t describe what was happening at home then. I couldn’t sit still at home. It seemed to me like some terrible plague had visited our family and killed my sisters. I cried with my parents. Then I understood everything that was happening around us.

After a few days, my two sisters Tola and Kazia came back home – the plucky girls had slipped through the Germans’ fingers and escaped from the train. I was very happy they had returned, but the distress and the pain that I suffered after they were taken will stay in my memory forever as the worst experience of the war.

Original Sources (Poland)

“This means war!” Polish Radio address on 1 September 1939

Radio address on the attack on Poland on September 1, 1939 in English.

Audio transcription: Polskie Radio (01.09.1939)

“[...] On the 1st of September 1939, at dawn, the Germans crossed into our territory. German air force and regular army unexpectedly invaded Polish territory without a declaration of hostilities.

[...] German airplanes have attacked a number of towns all over Poland. [...] Casualties have been reported among the civilian population. [...]”

1 September 1939: the beginning of hell

80th anniversary of the outbreak of the world war II

by Piotr Abryszeński / Translation: Alicja Rose & Alan Lockwood

“This means war. From now on, all other matters and issues become of secondary importance”, stated the message broadcast by Polish Radio on the morning of 1 September 1939. “We have set our public and private lives on a special track. We have entered war. The entire effort of the nation must go in one direction. We are all soldiers now. We need to think about only one thing: fighting until we win”. German aggression against Poland had begun the Second World War, a conflict that would consume 70-85 million lives over the next six years.

Poles had enjoyed a free state for a little over twenty years. Independence had been the dream of generations of Polish patriots, whose homeland had been taken from them as the result of partitions by neighbouring powers. When Poland regained its sovereignty, after 123 years and as a result of the First World War, it energetically began to rebuild its social, cultural and political life. The revived state first faced a deadly threat from Bolshevik Russia, which it was able to repel by mobilising the whole of Polish society. When the borders of Poland had finally been established and confirmed, Poles could at last enjoy their regained freedom and live in their own country.

From memoirs and diaries of that period, we learn that the summer of 1939 was extremely hot. On contemporary photos and postcards, you see crowds of smiling tourists and holidaymakers dressed in the fashion of that day. In the evenings, cafes and restaurants were crowded with regular guests, who would also visit cabarets and variety shows. In Warsaw alone, where a million people were living, there were 60 cinemas, big enough to accommodate thousands of filmgoers.

By autumn 1938, Hitler had already demanded that Poland consent to including the Free City of Danzig in the Third Reich, while delineating an extraterritorial highway and railway line connecting Danzig with Germany across the northern Polish region of Pomerania, or the “Pomeranian corridor”, as the Germans dismissively called it. Poland, rejecting Berlin’s demands, formalised an alliance with France and Great Britain. Unfortunately, the Polish-British treaty of 25 August 1939 did not stop altogether the coming invasion; it only postponed the attack by Germany. Rapprochement with Great Britain and France was fundamental and significant: it was a sign that Poland, faced with changes in the international arena, was supporting the West and rejecting offers of any cooperation with the Third Reich.

But at the end of August 1939, Polish towns and cities still did not believe that war would break out. It was widely believed that Berlin’s threats were only the megalomania of the German government. Jokes about Hitler and his associates were repeated in the press and on radio, and popular Warsaw cabarets, in both Polish and Yiddish, presented the latest jokes and mocked the screaming speeches of the Chancellor of the Third Reich. People believed instead in the Polish military, and believed in their allies, and in the League of Nations as the guardian of world order.

It was rather different in Pomerania. The number of Polish tourists at the seaside was lower than in previous years. Also noticeable were the concentration of German troops and heightened traffic across the border between the Third Reich and the Free City of Danzig. The atmosphere was more serious, as numerous acts of violence had long been happening against the Polish population there. Anti-Polish sentiments were skillfully fueled by propaganda directed by Joseph Goebbels. When Polish customs officers arrived in mid-August 1939 in Stutthof (now Sztutowo, a village on the Baltic coast, located about 38 km east of Gdańsk, at the base of the Vistula Spit), they observed preparations for construction works. They did not know that, under SS supervision, a concentration camp was being built there, which according to the original planning would have been larger than the eventual size of the sinister Auschwitz. Already on 2 and 3 September, the first transports of prisoners to KL [concentration camp] Stutthof took place. Among the first were members of the Polish intelligentsia and the clergy, soon joined by Jewish prisoners arrested in Gdańsk and nearby Gdynia.

Moscow, 23 August 1939 Friedrich Gauss, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Joseph Stalin and Vyacheslav Molotov (author Mikhail Mikhaylovich Kalashnikov; public domain)

The secret appendix to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact naming the German and Soviet spheres of interest (public domain)

On 23 August, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union signed a non-aggression pact. Executing the wishes of their leaders were the foreign ministers of both countries, Joachim von Ribbentrop and Vyacheslav Molotov. That agreement shocked public opinion globally. A secret additional protocol of the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact contained a provision on the division of the Polish state [...]. Polish historiography now defines this pact as the “fourth partition of Poland” [in reference to late 18th-century partitions]. The German-Soviet alliance also meant police cooperation, resulting in plans to exterminate Polish elites.

On the evening of 31 August 1939, an SS unit and a group of criminal prisoners dressed in Polish uniforms faked an assault on a German radio station in Gliwice, a city in Upper Silesia, in the south of Poland. This “Gliwice provocation” then became an excuse for aggression against Poland.

And already on 1 September, German bombs were falling on hundreds of Polish cities and towns; the majority of the victims of these bombs were civilians. German planes reached as far east as Grodno, and Warsaw was in flames. [...]

935 words

Source: 1 September 1939: The beginning of hell,

https://polishhistory.pl/1-september-1939-the-beginning-of-hell

last visited: 11/01/2021

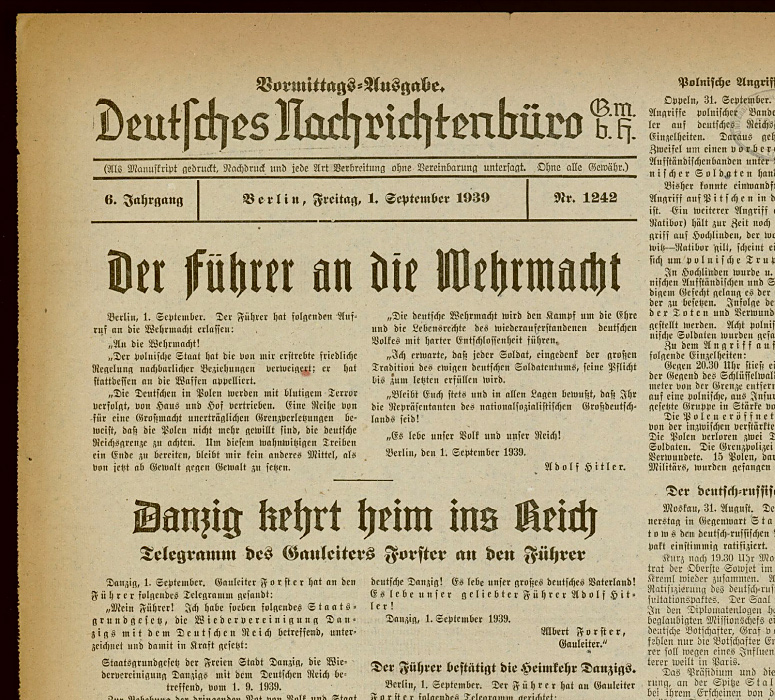

Original Sources (Germany)

Extracts from the morning edition of Deutsches Nachrichtenbüro GmbH, the official central press agency of the German Reich at the time of National Socialism, and the Teltower Kreisblatt, daily newspaper for the Teltow district of Friday, 1st September 1939

To the Wehrmacht!

The Polish state has refused the peaceful establishment of neighbourly relations which I was seeking; instead, it has appealed to arms.

Germans in Poland are being persecuted with bloody terror, driven from their homes and farms. A series of border violations, intolerable for a great power, proves that the Poles are no longer willing to respect the German Reich border. In order to put an end to this madness, I have no choice but to use violence against violence from now on.

The German Wehrmacht will lead the fight for the honour and essential rights of the resurrected German people with firm determination.

I expect every soldier, mindful of the great, undying tradition of German soldiering, to fulfil his duty to the last.

Remain aware at all times and in all situations that you are the representatives of National Socialist Greater Germany!

Long live our people and our Reich!

Berlin, 1 September 1939

Adolf Hitler

Polish attacks on German territory

Oppeln, 31 September [Note: probably typographical error - 31 August]. We now have more details on the reported attacks by Polish gangs and Polish guerillas [Note: members of a military volunteer association] on German territory. It has became clear that these were without doubt planned attacks carried out by Polish insurgent gangs with the participation of regular Polish soldiers.

So far it has been established beyond any doubt that an attack on Pitschen near Kreuzburg has taken place. Another attack on Hochlinden (northeast of Ratibor) is still ongoing. In particular, the attack on Hochlinden, thought to be taking place somewhere on the Gliwice - Ratibor road, seems to give a clear indication that Polish troops are involved.

In Hochlinden, the new customs house has been stormed by Polish insurgents and soldiers. After 1 1⁄2 hours of fighting, border police managed to reoccupy the customs house. Darkness is preventing the number of dead and wounded from being determined exactly. Eight Polish insurgents and six Polish soldiers have been captured.

The following details of the attack on Pitschen are still being reported:

Around 8:30 p.m. a border police patrol in the area of the Schlüsselwald near Pitschen – about 2 kilometres from the border, on German territory – encountered a Polish group of over 100 men, consisting of insurgents and military personnel.

The Poles immediately opened fire, which was returned by the border police, who had by then received reinforcements. Two Poles were killed, including one Polish soldier. The border police report one dead and several wounded. 15 Poles, including 6 members of the Polish military, have been taken prisoner.

The Führer confirms the return of Danzig

The Führer has sent the following telegram to Gauleiter Forster

To Gauleiter Forster, Danzig.

I accept the proclamation of the Free City of Danzig to return to the German Reich. I thank you, Gauleiter Forster, and all the men and women of Danzig, for the steadfast loyalty you have shown over so many years.

Greater Germany welcomes you from the heart. The law on reunification will be implemented immediately.

I appoint you Head of the Civil Administration for the Danzig Region.

Berlin, 1 September 1939

Adolf Hitler

Source: https://bit.ly/2ZXh5DL, last visited: 05/12/2021

Demonstration of loyalty to the Führer

Berlin, 31 August. The Führer’s generous offer to Poland to maintain and consolidate peace, and the rejection of this offer by the Polish government, were announced at 9 p.m. in a special announcement and on the evening news at 10 p.m. Immediately afterwards, many Berliners took the opportunity to go to Wilhelmsplatz late at night to express their loyalty to the Führer in this very grave hour.

Loudspeakers on the square informed the population about the political situation, and the news resounding far across the square attracted more and more Berliners. Particular satisfaction was expressed when the news of Russia’s ratification of the German-Russian agreement was announced.

Soon after, several Berlin newspapers were publishing extra editions which were literally ripped out of the hands of the distributors.

The Führer, in front of the Reichstag, Berlin, 1 September

The German Reichstag met this morning at 10 a.m. Shortly before 10 a.m. the Führer, who was wearing a field-grey uniform, drove up to the Reichstag. In the Reichstag building, he was welcomed by the President of the Reichstag, Field Marshal Göring, and immediately led to the government gallery. Thunderous applause from the members of parliament greeted the Führer at this hour.

In a dazzling address to the men of the German Reichstag and to the entire German people—dazzling, but charged with the profound seriousness of the times—the Führer expressed the unanimous and unbending will of the German nation to eliminate the intolerable conditions on the Reich’s eastern borders and to create a peace founded on justice.

A sacred but firm determination grips the men of the German Reichstag. The Führer speaks in clear and forceful words of the terrible hardships and dangers which have afflicted the German Reich and its people since the creation of the Polish Corridor twenty years before. He gives a list of the many proposals for revising these intolerable conditions. They have been rejected by the other side. In response to the observations of our opponents, the Führer explains with emphatic sharpness: We Germans have never considered the Diktat of Versailles to be law. The Führer then reviews the course of the negotiations with England and Poland in recent weeks.

At the time of going to press, the Reichstag session is still going on.

947 words

Source: https://bit.ly/3edfNrO, last visited: 05/12/2021

Other Lesson Materials

Children in World War II

Remembrance and memorialisation of World War II in different countries

Young people and forced labour during World War II

Border changes resulting from World War II

Consequences of World War II

Video: Clash of Memories